![]()

I’ve long felt that dismissive asshole music writers can be every bit as valuable as thoughtful and rigorous ones. Yes, a think piece on why it’s important that so-and-so’s reunion album is held as a disappointment by the cognoscenti and what that consensus might say about the cultural priorities of a generation can be thought provoking and illuminating, and I’m absolutely going to read that piece. But sometimes I only need to hear from the smugging, brickbat-lobbing prick who’ll just flat out tell me that a record is dog shit and that my money would be better spent on maybe a nice lunch. When the ‘zine explosion hit in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, I always particularly enjoyed titles like Forced Exposure, Your Flesh, and Motorbooty, some of whose writers would just absolutely SAVAGE a band for being even slightly sub-par—not because I had any particular hardon to see sincere creative strivers get slammed, but because these mags’ ranks were swelling with Bangs/Meltzer aspirants who did their best to be really damn clever with their invective. I succumbed to that temptation, myself, in my youth as an embryonic writer. Not gonna lie, ill-tempered nastiness could be (oh, who am I kidding with the past tense, still is) a great deal of fun, so long as it wasn’t a crutch, and I got validation for it from readers who found such caustic bastardy engaging and funny.

But a book I picked up back in the early oughts revealed to me a tradition for brutal critical smartassery reaching back long before the rock era. Nicolas Slonimsky’s Lexicon of Musical Invective, originally published in 1953, but revived with new editions in 1965 and 2000, contains hundreds of pages of critical blasts, going as far back as the turn of the 19th Century, at works that later became untouchables in the classical music canon. I’m normally one to seek out the oldest edition of a book I can affordably get my hands on, but in the case of the Lexicon, the 2000 publication not only holds the advantage of still being in print, it has a wonderful foreword by Peter “P.D.Q. Bach” Schickele, from whence:

It is a widely known fact—or, at least, a widely held belief—that negative criticism is more entertaining to read than enthusiastic endorsement. There is certainly no doubt that many critics write pans with an unbridled gusto that seems to be lacking in their (usually rarer) raves, and these critics often become more famous, or infamous, than their less caustic colleagues.

Most of us feel constrained, in person, to say politely pleasant things to creative artists no matter what we think of their work; perhaps this penchant of ours endows blisteringly bad reviews with a cathartic strength…

And perhaps much of the appeal of the Lexicon to a classical-music dilettante like me lies in how it’s all the more entertaining to read slams on works that are so long-embedded in our culture, so widely regarded as timeless works of surpassing genius, that it’s hard to even imagine some grump throughly torpedoing them.

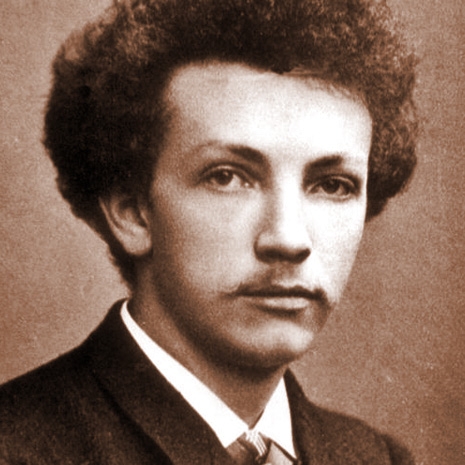

On Richard Strauss’ Salome:

“A reviewer…should be an embodied conscience stung into righteous fury by the moral stench with which Salome fills the nostrils of humanity, but, though it makes him retch, he should be sufficiently judicial in his temperament to calmly look at the drama in all its aspects and determine whether or not as a whole it is an instructive note on the life and culture of the times and whether or not this exudation from the diseased and polluted will and imagination of the authors marks a real advance in artistic expression.”

—H.E. Krehbiel, New York Tribune, January 23,1907

“I am a man of middle life who has devoted upwards of twenty years to the practice of a profession that necessitates a daily intimacy with degenerates. I say after deliberation that Salome is a detailed and explicit exposition of the most horrible, disgusting, revolting, and unmentionable features of degeneracy that I have ever heard, read of, or imagined.”

—letter to the New York Times, January 21, 1907

On Claude Debussy’s La Mer:

“M. Debussy wrote three tonal pictures under the general title of The Sea… It is safe to say that few understood what they heard and few heard anything they understood… There are no themes distinct and strong enough to be called themes. There is nothing in the way of even a brief motif that can be grasped securely enough by the ear and brain to serve as a guiding line through the tonal maze. There is no end of queer and unusual effects in orchestration, no end of harmonic combinations and progressions that are so unusual that they sound hideously ugly.”

—W.L. Hubbard, Chicago Tribune, January 30, 1909

“We believe that Shakespeare means Debussy’s ocean when he speaks of taking up arms against a sea of troubles. It may be possible, however, that in the transit to America, the title of this work has been changed. It is possible that Debussy did not intend to cal it La Mer, but Le Mal de Mer, which would at once make the tone-picture as clear as day. It is a series of symphonic pictures of sea sickness.”

—Louis Elson, Boston Daily Advertiser, April 22 1907

On Ludwig van Beethoven:

“Beethoven’s Second Symphony is a crass monster, a hideously writhing wounded dragon, that refuses to expire, and though bleeding in the Finale, furiously beats about with its tail erect.”

—Zeitung für die Elegente Welt, Vienna, May 1804

“Recently there was given the overture to Beethoven’s opera Fidelio, and all impartial musicians and music lovers were in perfect agreement that never was anything as incoherent, shrill, chaotic and ear-splitting produced in music. The most piercing dissonances clash in a really atrocious harmony, and a few puny ideas only increase the disagreeable and deafening effect.”

—August von Kotzebue, Der Freimütige, Vienna, September 11, 1806

“Beethoven always sounds to me like the upsetting of bags of nails, with here and there also a dropped hammer.”

—letter from John Ruskin to John Brown, February 6, 1881

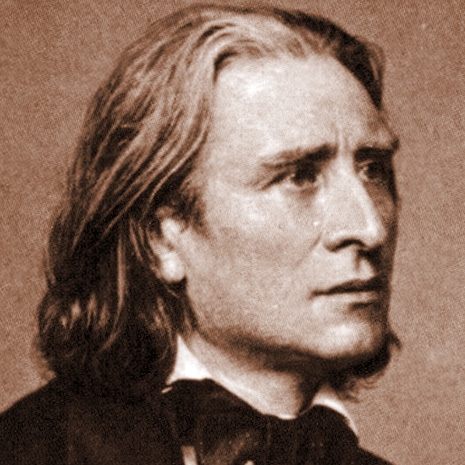

On Franz Liszt:

“Liszt’s Mephisto Waltz is a hideous, incomprehensible jargon of noise, cacophony and eccentricity, musically valueless, and only interesting to ears that prefer confusion to meaning… It had about as much propriety on the program with Schumann and Handel as a wild boar would have in a drawing room.”

—Boston Gazette, November 20, 1887

“There is no doubt that Liszt has satisfactorily described the Inferno. Nothing so suggestive of unceasing torment and the wails of the damned has ever been written by mortal man. Let us hope the good Abbé will never go to a place where his own music is exceeded.”

—Unidentified American newspaper, May 1882

“Bülow began with Liszt’s B-minor Sonata. It is impossible to convey through words an idea of this musical monstrosity. Never have I experienced a more contrived and insolent agglomeration of the most disparate elements, a wilder rage, a bloodier battle against all that is musical. At first I felt bewildered, then shocked, and finally overcome with irresistible hilarity… Here all criticism, all discussion must cease. Who has heard that, and finds it beautiful, is beyond help.”

—Edouard Hanslick, 1881