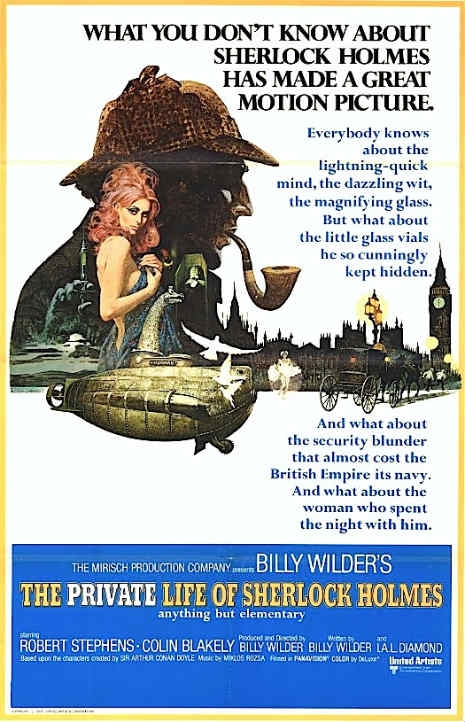

Billy Wilder spent seven years with his co-writer I. A. L. Diamond working on the script of The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes. The finished film originally lasted over three hours, but the studios panicked over the failure of such long form films (Doctor Doolittle with Rex Harrison, and Star! with Julie Andrews and Michael Craig) and demanded cuts. The film was hacked down to an acceptable 93 minutes. Diamond didn’t speak to Wilder for almost a year

It was a terrible act of vandalism that robbed cinema of one of its greater Holmes, as portrayed by Robert Stephens. It was also bizarre that Wilder, who believed in the primacy of the word, allowed his script to be so drastically altered, turning what was an original meditation on Holmes into a mildly distracting caper. In the process we lost Wilder and Diamond’s analysis of Holmes not as just a fictional creation, but in comparison to Shakespeare’s Hamlet.

The clues are all there to be found. Let’s start with the casting, Stephens, who was one of the most gifted and brilliant actors of his generation - who sadly only graced the screen in a handful of films: scene-stealing in A Taste of Honey, as the art teacher Teddy Lloyd in The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, and as the BFI states, “sublime” in The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes. Stephens was a stage actor, the heir apparent to Laurence Olivier indeed, in some respects, a far better actor than Olivier, who depended for success by flirting with the audience - Olivier could never be bad as he needed, demanded, the love of his audience.

When Wilder cast Stephens, the actor asked the great director:

‘“How do you want me to play it for the movie,” I asked Billy. “You must play it like Hamlet. And you must not put on one pound of weight. I want you to look like a pencil.” So, that’s the way we did The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes.’

When I first saw The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, I thought there was something missing, like a tale told through mime in a closed and darkened room. There was a story, but it seemed framed around a more interesting yet absent work. It puzzled me. If there had been more substance, I might have pondered it further. Instead, I thought Wilder’s movie less than the sum of its parts.

By cutting the movie in half, Wilder had taken out the story’s heart. His original intention to examine the private life of Sherlock Holmes no longer made any sense - what private life? We hardly see any instance of this at all, only subtle hints through Stephens’ fine performance, which suggests a man bruised and broken by failure in love.

The idea of Holmes as poorly romantic runs counter to Conan Doyle’s creation, of which he once remarked:

“Holmes is as inhuman as a Babbage’s calculating machine and just about as likely to fall in love.”

Though as we know, Holmes did fall, if not in love, then at least under the sway of one of the four people who got the better of the Baker Street detective, Irene Adler, as Watson explained in the opening of “A Scandal in Bohemia”:

‘To Sherlock Holmes she is always the woman. I have seldom heard him mention her under any other name. In his eyes she eclipses and predominates the whole of her sex. It was not that he felt any emotion akin to love for Irene Adler. All emotions, and that one particularly, were abhorrent to his cold, precise but admirably balanced mind. He was, I take it, the most perfect reasoning and observing machine that the world has seen, but as a lover he would have placed himself in a false position. He never spoke of the softer passions, save with a gibe and a sneer. They were admirable things for the observer — excellent for drawing the veil from men’s motives and actions. But for the trained reasoner to admit such intrusions into his own delicate and finely adjusted temperament was to introduce a distracting factor which might throw a doubt upon all his mental results. Grit in a sensitive instrument, or a crack in one of his own high-power lenses, would not be more disturbing than a strong emotion in a nature such as his. And yet there was but one woman to him, and that woman was the late Irene Adler, of dubious and questionable memory.’

Wilder’s interest in examining the “private” life of the world’s greatest fictional detective was retrospective, very much a 20th-century ailment, where everything is seen through the colored glass of psycho-analysis and political editing. Holmes cannot be viewed as he was intended - merely a product of Victorian times - but rather as damaged goods, like Hamlet carved by the hurt of private relationships. A hint as to what Wilder had intended was made by the excellent writer and biographer, Roger Lewis. In his essential collection of essays Stage People, which features fine portraits of such actors like Anthony Hopkins, Ian McKellan, Judy Dench, and Stephens, Lewis wrote:

...the film unfolded as an essay on women and their elegance, and Holmes’s justification for misogyny. He was found in love with a murderess; another inamorata died on the eve of their wedding; then there was Ilse von Hoffmanstahl, the film’s version of Irene Adler. Here was a Holmes fated to fail: a virtuoso empiricist degenerated to morbid dreaminess by amorous action. Hamlet traduced by a flotilla of Ophelias.

Wilder cast Stephens because ‘he looks as if he could be hurt’ - and it was a moody, intelligent portrayal: ‘He does not want courage, skill, will, or opportunity; but every incident sets him thinking…his senses are in a train of trance, and he looks upon external things as hieroglyphics’ - which is how Coleridge described the Prince of Denmark, Elsinore his Baker Street; a palace of puzzles.

Hamlet is engaged by the Ghost to discover who killed his father; he prefers to police, however, the free-wheeling nature of his own mind. He snoops out himself (in soliloquy). Holmes, too, creeps about inside his head - which distresses Watson, because it looks like catatonia: ‘The outbursts of passionate energy when performed the remarkable feats with which his name is associated were followed by reactions of lethargy, during which he would lie about with his violin and books, hardly moving, save from sofa to table.’ And this sort of description, or admission, intensifies the enigma of his personality.

Unfortunately, The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes was radically re-edited, eradicating its atmosphere and tempo. What should have been a triumphant commentary on Hamlet became a 1960s romp, What’s New Pussycat? in the costumes of the gasolier period. (Wilder had even gone to the trouble of casting Stanley Holloway as a grave digger - the part he’d played in Olivier’s Hamlet in 1948.)

The finished film was originally three hours and two minutes long, and consisted of four cases for Holmes and Watson to solve. After the Mirisch Brothers “got frightened” Wilder trimmed it to one hour and 53 minutes. It wrecked the film, but even in its released form, The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes was handsome enough to win a cult following, and some mild praise from the critics.

For Lewis, the issue of the lost sections excited him “as Jeffery Aspern’s burnt letters….or Byron’s memoirs on Jock Murray’s grate.”

Allen Eyles, in Sherlock Holmes: A Centenary Celebration, has done his own sleuthing on the tattered opus. He reports that the ‘Naked Honeymooners’ too place on an ocean liner, where a pair of young lovers lie dead in bed. Holmes, conducted by Watson, sauntered to the scene of the crime - only to discover he’s in the wrong cabin, poking and prodding quite the wrong prostrate bodies. Then there was the ‘The Case of the Upside Down Room’..[a murder is committed] in a chamber owned by a blind David Kossoff - where the chairs, tables and bed are dizzyingly stuck to the ceiling. It transpires to be all a ruse, organized by an ingenious Watson, to shake Holmes from his well of accidie. In this episode, as in a sacrificed epilogue, where Holmes is asked to help catch Jack the Ripper, Inspector Lestrade appeared, played by George Benson.

Most damaging, perhaps, was the forfeiture of a flashback to Holmes at Oxford, skulling on the Isis and falling in love with a girl - whom he discovers to be a prostitute. If the ‘Naked Honeymooners’ and ‘Upside Down Room’ were squandered because more or less self-contained, and larky, the Oxford affair and the Ripper case (the victims, of course, all Whitechapel prostitutes) importantly deepened the film’s major theme: Holmes entangled in the world of emotion, rather than of reason.

What we are left with now pales before what should have been. Understandable then that Diamond took such umbrage with his writing partner, Wilder. That said, The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes has seen its reputation grow over the years, until now, it has been described by Kim Newman as:

“A true evocation of the spirit of the Strand Magazine, this is the best Holmes movie ever made and sorely underrated in the Wilder canon.”

And by Andrew Sarris as:

“Wilder’s second most underrated masterpiece.”

In terms of Wilder’s oeuvre, this may all be true. But for me the film robs the viewer of the full extent of Robert Stephens’ incomparable performance as Sherlock Holmes, which even in its incomplete and poorly edited state, is still one of the greatest ever captured on screen. And where else will we find a more suitably irascible and dedicated Watson than in Colin Blakely? Or, a better Mycroft in Christopher Lee? Or, such a score by Miklós Ròzsa?

Sadly, You Tube has been denuded of clips from the film, but you can see one scene with Stephens, Blakely and Lee here.