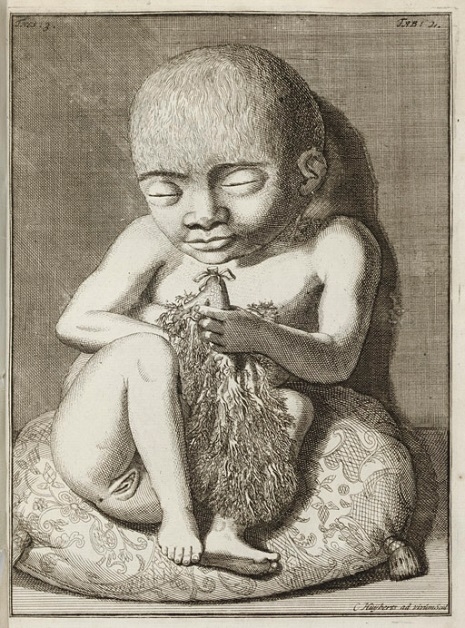

The drawings you see are here are from Frederik Ruysch’s Thesaurus Animalium Primus, a ten-volume collection published between 1701 and 1716. Ruysch was a Dutch botanist and anatomist who was appointed chief instructor to all the midwives in Amsterdam in 1668. His position had never existed before, but if a woman wanted to continue her work as a midwife, she now had to be evaluated by Ruysch. Having formerly suffered a dearth of cadavers to study and preserve, he suddenly found himself with access to a profusion of dead babies.

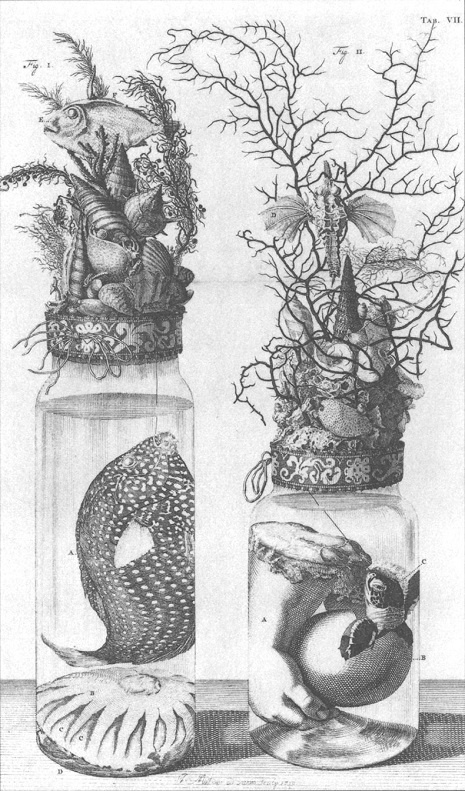

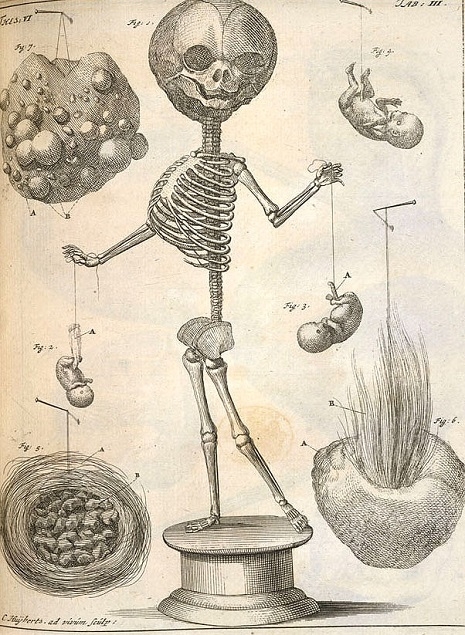

Part scientist, part artist, and part absolute eccentric, Ruysch became famous for his beautiful and morbid displays of embalming and remains, arranging human and animal parts together in the sorts of elaborate scenes you see here. Though he was a respected scientist, these presentations were barely medical, and hardly scientific. The sculptures often positioned the bones of babies in impossible stagings—you’ll notice one weeps genteelly, with a handkerchief. And with the help of his daughter Rachel, a famous still-life painter in her own right, he adorned his works with hair, flowers, fish, plants, seashells, and lace.

Ruysch showed his creations in a private museum (entry free to doctors, paid to layman), and they quickly became world-famous. The museum wasn’t quite a sober affair either—Ruysch would arrange tongue-in-cheek exhibits, like the bones of a three-year-old-boy next to that of a parrot, with the insinuated joke of “time flies.” In 1697, Czar Peter the Great took a tour of Ruysch’s work and became so enamored with one of the specimens that kissed it. He eventually purchased the entirety of the museum. I’m unsure of Dutch cultural norms regarding death around the turn of the 18th century, but the fact that midwives had to answer to a man with a side business in death sculptures suggests, at the very least, a conflict on interest. Still the strange beauty of Ruysch’s work cannot be denied, nor can his scientific brilliance.

His pioneering embalming techniques are what made his work possible, and Peter the Great also paid quite handsomely for the secret recipe to his preservation fluid, an alcohol of clotted pig’s blood, Berlin blue and mercury oxide. A (false) rumor circulated that the sailors transporting Ruysch’s collection to Russia drank all his embalming fluid, but it actually arrived in whole, and some of Ruysch’s specimens are still in perfect condition today—a testament to his brilliance in preservation.

Jan van Neck’s “Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Frederick Ruysch,” where he appears to perform an autopsy for posterity. (1683)

Via The Public Domain Review