In the right circumstances of time, place and imagination—it is possible to time travel. This was firmly impressed upon me in my teens while reading Christopher Isherwood’s Goodbye to Berlin. I had just moved to Glasgow as a student and was renting a room in an apartment owned by a birdlike lady who whistled music hall songs and sniffed pecks of snuff off the back of her hand. She was long retired. Renting a room supplemented her meagre state pension. Now here’s the connection: she had once been a furrier in Berlin during the 1930s and had witnessed at first hand the rise of Adolf Hitler and the Nazis. She had seen the Jewish shops vandalized and some of her Jewish friends disappear to who knew where?

It wasn’t just the fact this dear old lady had an experience of the events which I was reading in Mr. Isherwood’s book—but the flat in which I was a lodger had been untouched since the 1930s. The whole interior, its decoration, the heavy furniture, the coal fire, the carpeting and rugs, the cast iron bed, the wooden mantlepiece, the dressing table with polished vanity mirror—everything in this apartment was as it had been in the days just before the Second World War.

Only in the kitchen was there a slight capitulation to modern technology. A 1950s fridge and an electric cooker unused—still wrapped in its protective polythene. I cooked simple meals off a bunsen burner gas ring—a blackout cooker as my landlady called it. It was winter. The apartment was cold. At night I could hear, like Herr Issyvoo, the men outside whistling in the dark. Except these men were not calling up to their lovers to come to the windows but to their dogs off somewhere in the small misty park below. In such circumstances of place and time and imagination, it was all too easy to find myself transported to the decade of Goodbye to Berlin.

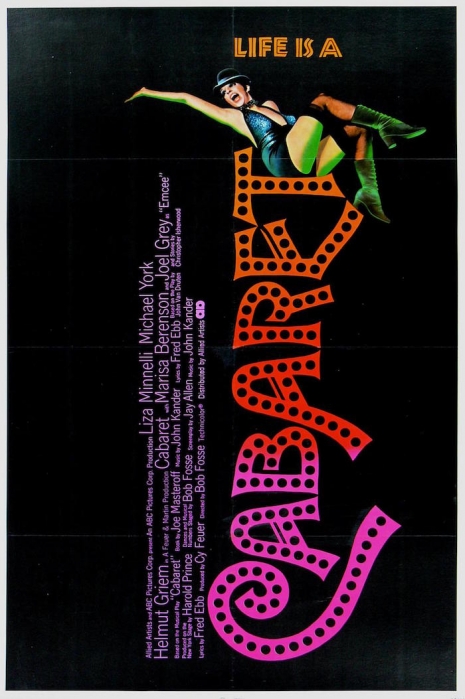

That snowbound Christmas I watched Cabaret on television. A multi-award-winning film version of the musical inspired by Isherwood’s Berlin novels. I must have seen that film about thirty times since. It is an almost perfect movie—story, character, sex, politics, and a powerful overarching narrative. Not to mention Liza—with a “Z”—Minnelli at the very height of her talents. Based mainly on the short story “Sally Bowles” from Goodbye to Berlin and John Van Druten’s adapted play of the book I Am a Camera, Bob Fosse’s film Cabaret brilliantly captured the world of Isherwood’s writing.

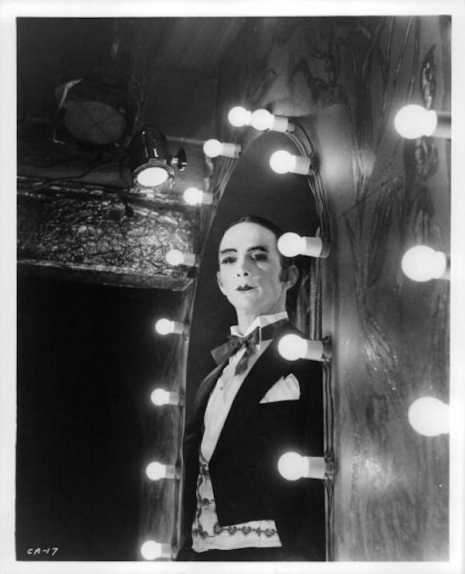

The film starred Michael York as Isherwood’s alter ego—named here Brian Roberts, Liza Minnelli as night club singer Sally Bowles, Helmut Griem as rich playboy Maximilian von Heune and the incomparable Joel Grey as the Master of Ceremonies at the Kit Kat Klub.

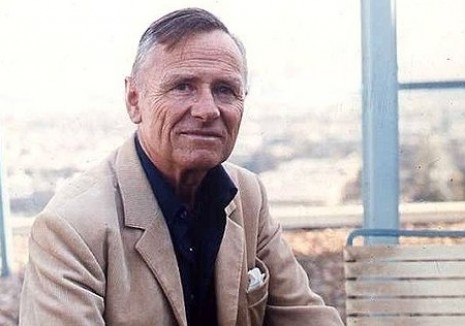

Apparently director Bob Fosse wanted to play the MC himself but the studio insisted on Grey. The film was shot at the Bavaria Film Studios in Germany—well out of Hollywood’s reach. One day the studios cabled Fosse to say he was spending too much money on smoke for the nightclub scenes. Fosse read the telegram out to the assembled cast. Then he ripped it up and threw it over his shoulder. That was the end of Hollywood’s involvement. Fosse had been considered a risky choice as director. His previous film Sweet Charity had flopped disastrously. Away from the studio’s interference, Fosse was able to achieve what he wanted. Cabaret swept eight Academy Awards from ten nominations.

Joel Grey as the Master of Ceremonies.

More photos from the making of ‘Cabaret,’ after the jump…