Two days ago Marc Maron’s WTF interview with Paul Thomas Anderson, who is promoting his new Thomas Pynchon adaptation Inherent Vice was posted, and buried in that interview is an intriguing tale about Anderson’s days as a student in a class taught by revered author David Foster Wallace. It turns out that Wallace spent a year as an adjunct professor at Emerson College, and that happened to be the same year that Anderson was there as a student, and Anderson happened to take one of Wallace’s classes, in which they apparently read Don Delillo’s classic postmodernist novel White Noise.

Here’s the relevant portion of the interview, which takes place around the 38th minute, lightly edited for readability:

Anderson: [Being at Emerson College] just felt like a drag. It didn’t really. … And I would have to say, that probably was just because I didn’t find a teacher that kind of spoke to me. The funny thing was, is when I was at Emerson for that year, David Foster Wallace, a great writer who was not known then, was my teacher. He was an English teacher. And, it was the first teacher I fell in love with. And I never found anyone else like that at any other schools that I’ve been to, which makes me really reticent to talk shit about schools or anything else, because it’s just like anyplace, like if you could find a good teacher, man, I’m sure school would be great.

Maron: So why didn’t you stay?

Anderson: He left.

Maron: So you were there with him for a year?

Anderson: Yeah.

Maron: And you spent a lot of time with him?

Anderson: You know why I didn’t stay? And in that classic move, I thought, “Oh, I want to get to New York. That’s where I’m supposed to go. I’m supposed to go to NYU,” ‘cause it had this good rep and all that. … And, dummy that I am, I did it, and I got there and I thought, “Well, I don’t want to be here. I wish I was back in Boston, you know, taking English classes.”

Maron: Did you spend a lot of time with David Foster Wallace?

Anderson: No. Just in class.

Maron: Oh really? You weren’t one of those guys that after class was like, “Hey, can I talk to you?”

Anderson: No. Uh, I called him once. He was very generous with his phone number, he said “Call me if you got any questions.” I called him a couple times.

Maron: Yeah? What did you say?

Anderson: I ran a few ideas by him about a paper I was writing. I was writing a paper on Don Delillo’s White Noise.

Maron: “Hail of bullets!”

Anderson: And I came up with a couple of crazy ideas, I don’t remember how the conversation went but I just remember him being real generous at like, you know, midnight the night before it was due.

Maron: Really? You were freaking out, all jacked up?

Anderson: [Laughing] Yeah, basically!

Maron: “I’m almost done, man!”

Anderson: It was like, I think I’d written a pretty good paper. It was like, cooking a pretty good dish and at the last minute just panicking—“I got to add some more shit on, on top of it.”

Maron: Or you missed the point, like “Aww, that’s what it’s about!”

Anderson: Right. Yeah. There was no cut-and-paste back then, if you typed it out, you were….

Maron: That book was a life-changer for me, man.

Anderson: Was it really?

Maron: Little bit.

Anderson: I’d love to go back and read it again.

Maron: I would too, actually.

As it happens, Wallace paid close attention to at least two of Anderson’s movies, Boogie Nights and Magnolia, without ever betraying any inkling that he had ever had contact with the director, which frankly seems a little odd. Wallace had a prodigious intellect, and even if Anderson were the most anonymous shnook Wallace had ever had as a student—which seems unlikely—if you’re on the phone multiple times with him discussing White Noise, when a movie as big as Boogie Nights comes out just six years later (Anderson’s debut film, Hard Eight, came out just five years later), you’d think it might make a more lasting impression in a mind as capacious as Wallace’s. Be that as it may, Wallace had strong opinions about Boogie Nights and Magnolia, opinions that track my own precisely: he was tremendously impressed by Boogie Nights and didn’t much care for Magnolia.

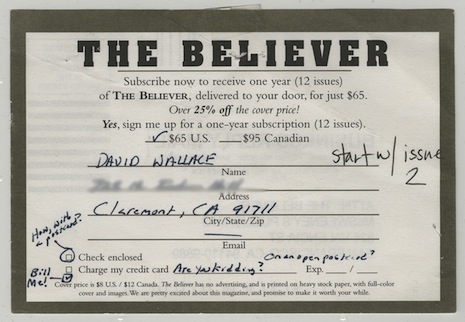

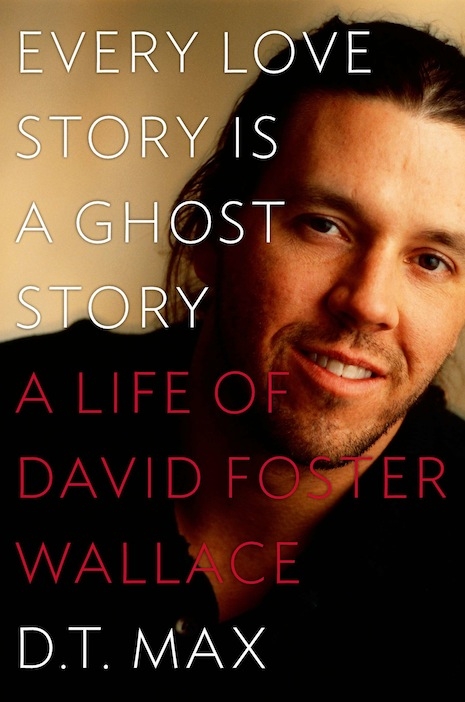

In Every Love Story Is a Ghost Story, the biography of Wallace that came out after Wallace’s 2008 suicide, author D.T. Max reports the following: “When Boogie Nights came out in 1997, Wallace called Costello and told him the movie was exactly the story that he had been trying to write when they lived together in Somerville.” “Costello” here is Mark Costello, a close friend of Wallace’s with whom he co-wrote the bizarre 1990 book Signifying Rappers: Rap and Race in the Urban Present. About Anderson’s follow-up to Boogie Nights Wallace was a good deal grumpier; according to Max’s account, Wallace “hated the acclaimed Magnolia, which he found pretentious and hollow, ‘100% gradschoolish in a bad way.’”

It’s tempting to say that Anderson (whatever Wallace thought of Magnolia) is the only director who could ever successfully direct one of Wallace’s works, and so on. Anderson is such a gifted director that he would be the first choice for almost any writer’s works, whether it be Delillo, Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian, J.D. Salinger. He has just completed the first Pynchon adaptation with a fair degree of success. Of course, there already exists a Wallace adaptation, John Krasinski’s 2009 movie Brief Interviews with Hideous Men. It happens that Jason Segel is attempting to portray Wallace himself in The End of the Tour, an adaptation of David Lipsky’s memoir about Wallace titled Although of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself. Segel has come under fire for daring to attempt to play Wallace, which makes sense primarily insofar as it’s exceedingly difficult to capture an intelligence like Wallace’s onscreen, and Segel has mostly played dumb guys in his career.

What’s been overlooked in the apparent linkup between Anderson and Wallace is a key shared point of interest, that being the adult entertainment industry. Anderson’s breakthrough success, Boogie Nights, is an affectionate look at the porn industry of the 1970s, which in the movie is eventually usurped by the more cutthroat and impersonal video-based porn industry of the 1980s, mirroring a progression that happened in real life. Anderson grew up in the San Fernando Valley and has often told of his youthful adventures figuring out that certain houses in the neighborhood were being used for porno shoots. (The subject comes up in the WTF interview too.) Wallace also had a keen interest in the porn industry, writing a piece of reportage for Premiere magazine on the AVN Adult Entertainment Expo in 1998. The article was hilariously written under the pseudonymous byline “Willem R. deGroot and Matt Rundlet”; the title of the piece was “Neither Adult Nor Entertainment.” It’s the first essay in Consider the Lobster, Wallace’s second collection of non-fiction works, although the title’s been changed to “Big Red Son.”

But the AVN story is just a small part of it. At one point, around the time he and Costello were working on the hip-hop book, Wallace, according to Max, spent a considerable amount of time trying to write a novel set in the pornography industry, one that never got finished:

Another nonconformist industry now caught his eye: the pornography business. Pornography fit well into Wallace’s ongoing areas of inquiry: it linked to advertising—the thing really being sold was the idea that we are all entitled to sexual pleasure, which in turn feeds the secondhand desire that Wallace saw at the root of the American malaise.

You can see this idea playing out in Wallace’s masterpiece Infinite Jest, in the “samizdat” that is so entertaining that its viewers lose interest in everything else and eventually die. In The Review of Contemporary Fiction, Costello (pretty hilariously) reported on Wallace’s research methods for the book as follows:

Wallace set timetables for his work, intricate as the Croton-on-Hudson local. Get up. Talk on phone with porn actress famous for giving screen blow jobs. Hang up. Ask: is the porn queen an actress? Look up actress in the OED. Actress: a female actor. Look up actor: one who acts in a drama. Surely a blow job is an act. OK then: is a blow job drama?

Not surprisingly, per Max, Wallace soon came to think that some “actual on-set knowledge might help.” It’s in this context that Wallace’s interest in Boogie Nights becomes more evident. According to Max, Wallace “came to think that what was needed was a reported piece on how the industry had changed as the so-called golden age of porn gave way to the era of inexpensive and inartistic video,” which is precisely the perspective that Anderson offered in his highly confident and knowing movie about porn.

Here’s The Dirk Diggler Story in full, the half-hour movie Anderson made in 1988 that many years later would become the core of Boogie Nights.