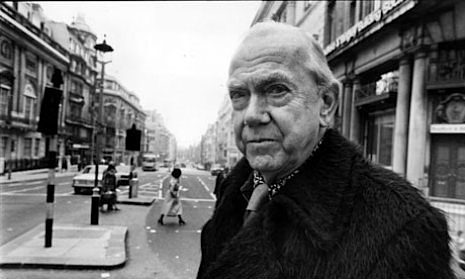

If the first volume of his autobiography A Sort of LIfe is to be believed, then the novelist Graham Greene did not have a very auspicious childhood.

His earliest memory was of sitting in his pram atop a hill, with a dead dog at his feet. When he was five, Greene walked with his nurse close to an alms-house, outside of which a crowd had gathered. Suddenly a man rushed forward and into the building. It was said he was about to cut his throat. Greene and his nurse waited among the wide-eyed spectators, until the man appeared at an upper window and cut his throat. Greene did not recall the latter part, but his brother Raymond confirmed what happened.

Another unpleasant memory was of “a tin jerry full of blood:” Greene had just had his “adenoids out and tonsils cut.” It all reads like the memoir of one of his fictional characters, Minty say, from England Made Me. Yet, if this was not enough Blud und Tod for a budding psychologist, Greene adds in details of a recurrent nightmare:

...I was terrified by a witch who would lurk at night on the nursery landing by the linen-cupboard. After a long series of nightmares when the witch would leap on my back and dig long mandarin finger-nails into my shoulders, I dreamt I turned on her and fought back and after that she never again appeared in sleep.

Dreams, we are told, were important to Greene: “the finest entertainment known and given rag cheap,” and he claimed two of his novels and several short stories “emerged” from his dreams.

He also suffered what he described as “terrors”: a dread of birds, and bats, and a “recurring terror of the house catching fire at night”.

In his teens, Greene had a breakdown, caused by “the interminable repetitions” of school life, “its monotony, humiliation and mental pain.” It led him to seek “forms of escape”: he cut his leg in a misguided attempt at suicide; “drank a quantity of hypo under the false impression it was poisonous”; downed a bottle of hay-fever drops, which contained a miniscule amount of cocaine; picked and ate some deadly nightshade, which had a slightly narcotic effect; and swallowed twenty aspirins before swimming in the empty school baths.

Greene was sent for psychoanalysis, where he “nearly” fell in love with his analyst’s wife, and soon after with another patient (a ballet student). He then began to invent answers in response to his analyst’s probing questions, but fails to reveal if his analyst was fooled by his dissembling.

In 1923, at the age of sixteen, Greene found a pistol in a corner cupboard in the bedroom he shared with his brother.

The revolver was a small ladylike object with six chambers like a tiny egg-stand, and there was a cardboard box full of bullets. I never mentioned the discovery to my brother because I had realized the moment I saw the revolver the use I intended to make of it. (I don’t to this day know why he possessed it; certainly he had no licence, and he was only three years older than myself. A large family is as departmental as a Ministry.)

With his brother away (rock-climbing in the Lake District), the revolver was “to all intents” Graham’s own. Greene wrote that he knew what he wanted to do with it, having been inspired by a book he had read on White Russian officers, who bored with inaction in the frozen reaches of their country would invent ways to literally kill time:

One man would slip a charge into a revolver and turn the chambers at random, and his companion would put the revolver to his head and pull the trigger. The chance, of course, was five to one in favour of life.

Writing almost 50-years after the event, Greene builds on his self-mythologizing by explaining how he would have described these events if he had been dealing with an imaginary character:

...I might feel it necessary for verisimilitude to make him hesitate, put the revolver back into the cupboard, return to it again after an interval, reluctantly and fearfully, when the burden of boredom and despair became too great.

This, of course, is only to show how Greene’s “burden of boredom and despair” was far greater than any contrived fiction. He knows automatically what he will do with the revolver. His life has become so dull that he could take “no aesthetic interest” in anything others may describe as beautiful—Greene felt nothing. His “boredom had reached an intolerable depth…” and he was “fixed, like a negative in a chemical bath.”

The scene now set, Greene begins his tale:

Now with the revolver in my pocket I thought I had stumbled upon on the perfect cure. I was going to escape in one way or another…

Unhappy love, I suppose, has sometimes driven boys to suicide, but this was not suicide, whatever a coroner’s jury might have said: it was a gamble with five chances to one against an inquest. The discovery that it was possible to enjoy again the visual world by risking its total loss was one I was bound to make sooner or later.

I put the muzzle of the revolver into my right ear and pulled the trigger. There was a minute click, and looking down at the chamber I could see that the charge had moved into the firing position. I was out by one. I remember an extraordinary sense of jubilation, as if a carnival lights had been switched on in a dark drab street. My heart knocked in its cage, and life contained an infinite number of possibilities…

This experience I repeated a number of times. At fairly long intervals I found myself craving for the adrenalin drug, and I took the revolver with me when I returned to Oxford….

Then it was a sodden unfrequented lane. The revolver would be whipped behind my back, the chamber twisted, the muzzle quickly and surreptitiously inserted in my ear beneath the black winter trees, the trigger pulled.

Slowly the effect of the drug wore off—I lost the sense of jubilation, I began to receive from the experience only the crude kick of excitement. It was the difference between love and lust.

Back home, Christmas 1923, Greene “paid a permanent farewell to the drug.”

As I inserted my fifth dose, which corresponded in my mind to the odds against death, it occurred to me that I wasn’t even excited: I was beginning to pull the trigger as casually as I might take an aspirin tablet. I decided to give the revolver—since it was six-chambered—a sixth and last chance. I twirled the chambers round and put the muzzle to my ear for a second time, then heard the familiar empty click as the chambers shifted. I was through with the drug…

Though he suffered from bouts of “boredom” or rather depression in later life, Greene never repeated his gamble with death again. His brother Hugh, however, was skeptical of Graham’s story, and it has been suggested Greene would have known exactly where the single bullet lay in the chamber by the weight of the gun.

Why Graham Greene indulged in this game of Russian roulette is perhaps explained by the particulars of his childhood. His father was headmaster at Berkhamsted School. The family were domiciled in one part of the house, the other part doubled as the school rooms. The symbolic point of entry from one world to the other was through “a green baize door,” just beyond his father’s study.

At home, his mother was distant, and the young Greene could have no close affiliation with his father, as he was his headmaster.

While at school, Greene was viewed as a “Quisling,” a collaborator with the classroom enemy, someone not to be trusted by the other pupils. It left Greene isolated and desperately alone.

The thirteen weeks of a term might just as well be thirteen years. The unexpected never happens. Unhappiness is a daily routine. I imagine that a man condemned to a long prison sentence feels much the same. I cannot remember what particular item in the routine of a boarding-school roused this first act of rebellion—loneliness, the struggle of conflicting loyalties, the sense of continuous grime, of unlocked lavatory doors, the odour of farts (it was sexually a very pure house, there was no hint of homosexuality, but scatology was another matter, and I have disliked the lavatory joke from that age on). Or was it just then that I suffered from what seemed to me a great betrayal?

This sense of betrayal was to influence all of Greene’s life and fiction—it is the theme in the majority of his writing, and a factor in his relationships with others. It was also the subconscious influence on his near fatal actions in 1923—for Greene there could be no better self-vindication than the attempted betrayal of his own life.

Below, the Channel 4 News obituary of the writer, with contributions from Anthony Burgess, Richard Attenborough and Auberon Waugh.