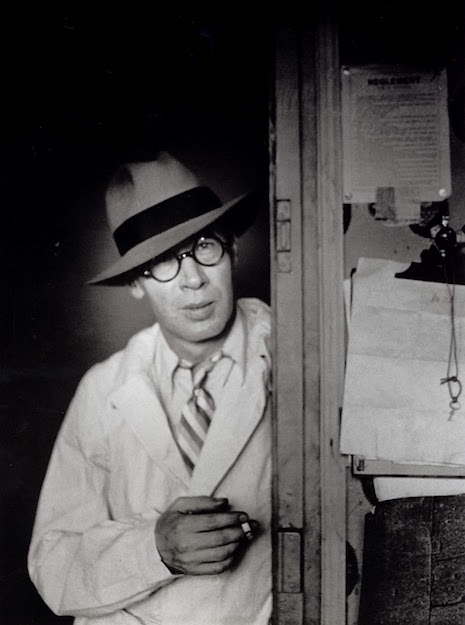

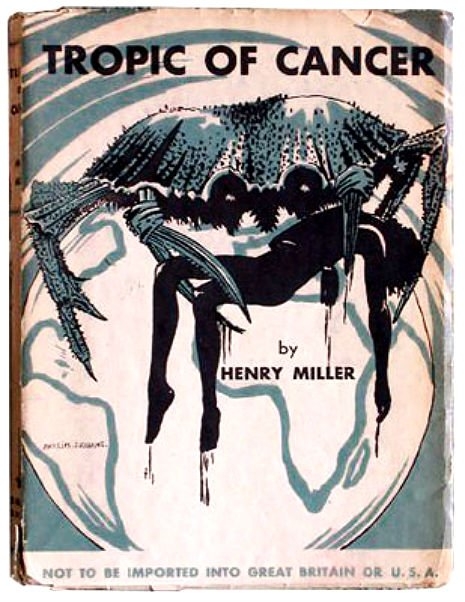

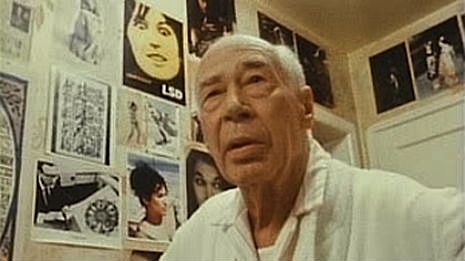

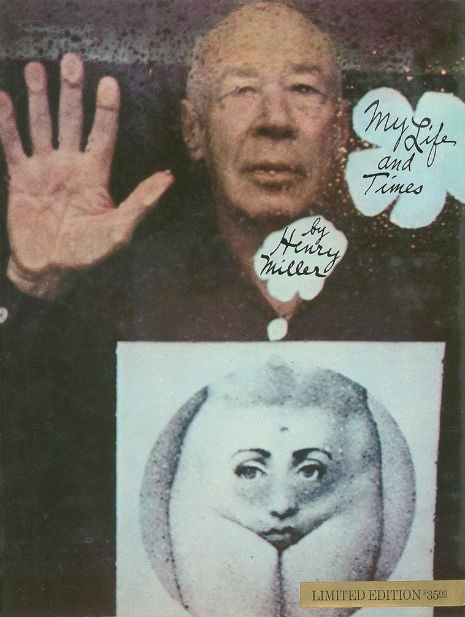

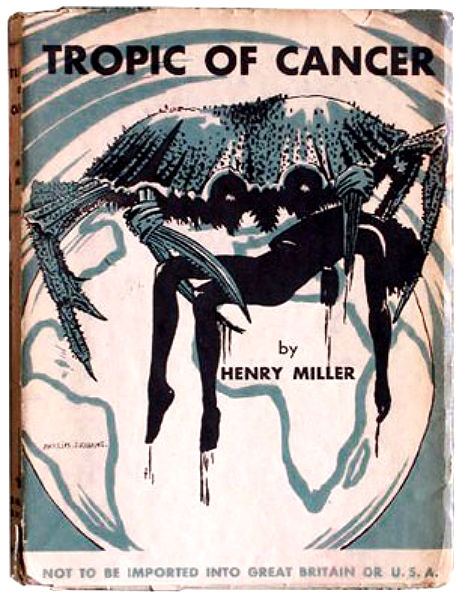

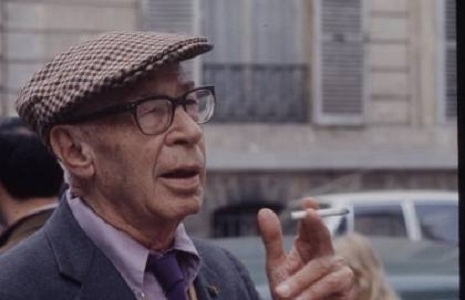

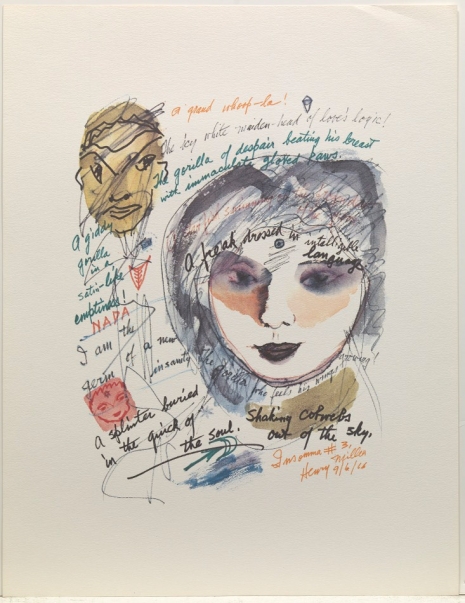

In the mid ’60s, Henry Miller, the great and often controversial American writer whose works were mostly banned in the US until 1961, developed an infatuation on a Japanese lounge singer and actress named Hoki Tokuda. Miller and Tokuda would eventually marry (a true May-December affair—their age difference was almost 50 years, and the marriage was reportedly…unconventional in other respects as well), but before sealing the deal, fretfulness over their relationship would provoke a prolonged bout of insomnia in Miller, and during that spell of sleeplessness, he produced a series of watercolors and the short story “Insomnia or the Devil at Large.” Miller described the watercolors thusly:

They reflect the varying moods of three in the morning. Some were sprinkled with bird seed, some with songes, and some with mensonges. Some dripped from the brush like pink arsenic; others clogged up on me and came out as welts and bruises. Some were organic, some inorganic, but they were all intended to lead their own life in the garden of Abracadabra.”

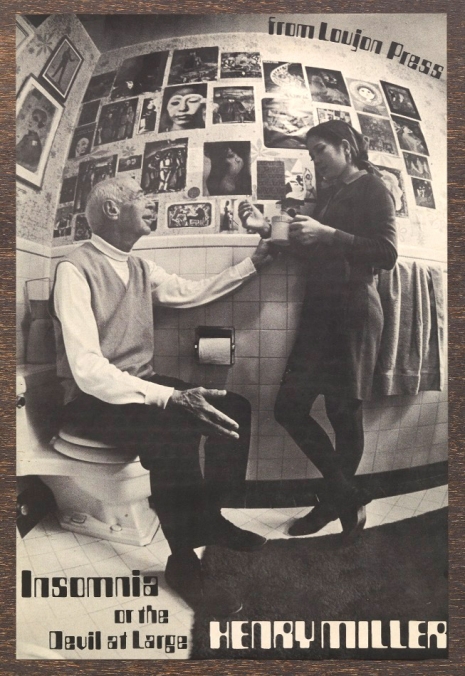

“Insomnia” would eventually see its most widely-distributed publication as a 33-page book in 1974, but in 1970, Loujon Press of Albuquerque, NM produced a rather lavish boxed portfolio featuring 17x22” reproductions of the Insomnia watercolors and a letterpress book containing the story. Several editions were made, with the intention of producing 999 boxes in all, but the reality was somewhat more modest. Evidently only about 300 of the wooden cases were made, and the editions, designated with letters A through F, were all published in smaller numbers than originally hoped, some in cheaper boxes, some in an “economy” edition comprised of simply the book and prints with no case at all.

One of the nicer sets, from edition G, has just come up for bidding via the Aspire Auction company. Its provenance is about as direct as can be—it was procured directly from Miller himself by a book and art dealer named Arthur Feldman, and it’s signed.

Insomnia or The Devil at Large”, book and a portfolio of twelve works, 1970. Lithographs on paper, book with comb binding, marked Edition G out of 385 copies to colophon, first edition, signed and dated by the artist “May 1st 1970”, published by Loujon Press, Albuquerque, NM. In wooden box with sliding lid, overall 24” x 19 ⅛”

Bidding closes on Thursday, April 6th. Best of luck. The images that follow are from the copy being offered for sale, and are culled from the auction house’s web site. Clicking spawns an enlargement.

More after the jump…