For a couple of years when I was a little kid—before I discovered rock music, so like 3rd and 4th grade—I collected Charlie Chaplin movies that I purchased on 8mm film from Blackhawk Films. Blackhawk sold newsreels of the Hindenburg disaster and WWII along with the public domain silent horror films of Lon Chaney and comedies by Chaplin, Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd. Blackhawk advertised in comic books, Famous Monsters of Filmland and in a nostalgia magazine my grandfather used to read (I wish I could recall the name of it, I’d buy every issue on eBay). I sent for their free catalog. The price of the Chaplin shorts ranged from like $7.98 to $14.98 which was an astronomical amount of money at that time, for someone who was eight years old, or otherwise. When I say “collected,” I probably had like seven Chaplin shorts that I got from Blackhawk. I’d tell my parents and grandparents just to give me money for Christmas and birthdays so I could order them. A $10 reward for a good report card meant another Chaplin film. I would screen them in my parents’ basement on a moldy-smelling Westinghouse 8mm projector my father had long ago lost any interest in.

I was really, really Chaplin obsessed. I still am to this day.

Charles Chaplin’s My Autobiography was published by Simon & Schuster in 1964, when the great man was then in his seventies and living a life of comfortable exile at Manoir de Ban, a 35-acre estate overlooking Lake Geneva in Switzerland, having been pushed out of Hollywood during the Red Scare. It’s one of the most extraordinary books that I’ve ever read. The first portion of the book describes, in brutal detail, the life of crushing Dickensian poverty that Chaplin and his brother Sydney were thrust into when their mother—who’d gone mad from syphilis and malnutrition—had to drop them off at the pauper’s workhouse, unable to care for herself, let alone them.

Chaplin’s remarkably beautiful prose is nothing short of heartbreaking. It’s not just the harsh Victorian circumstances he’s describing that are so excruciatingly Dickensian, it’s the quality of his writing as well. My Autobiography starts off exactly like a lost novel by Charles Dickens, and indeed there is probably no greater true life rags to riches story that has ever been told in the entire history of humankind. Chaplin went from being an innocent young boy who’d had his head shaved and painted with iodine for a lice treatment (there’s a group shot in the book that will hit you in the gut) in the lowest of circumstances to being the most famous man in the world just a few years later. It’s one of the best books that I’ve ever read and it’s one that will still be read long into the future as long as we don’t go the way of Planet of the Apes.

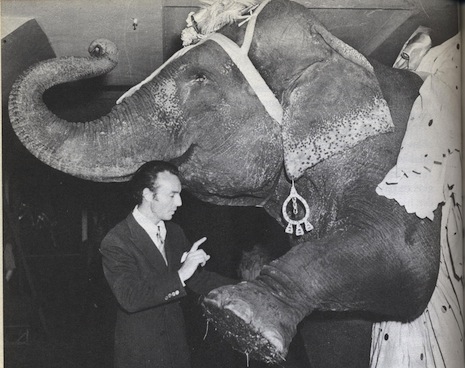

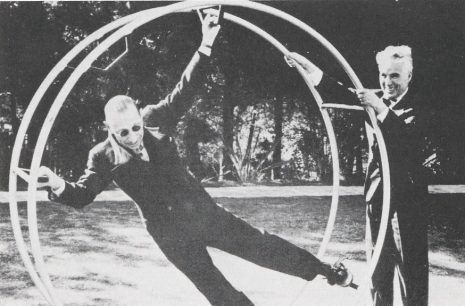

Stravinsky takes a spin on a hoop contraption that Chaplin had built at his Beverly Hills home.

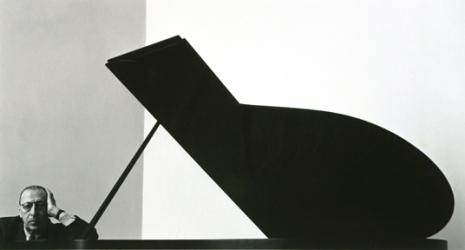

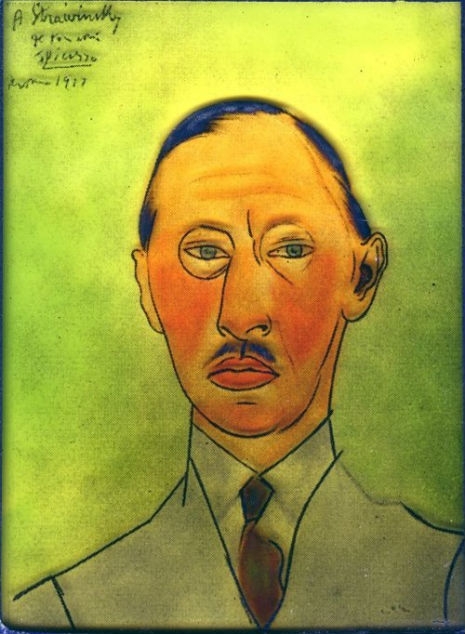

And speaking of our puzzling new Bizarro World national reality, there’s an anecdote that happens later in Chaplin’s book (pages 395-397) where he writes about a meeting that he had with Russian composer Igor Stravinsky where he proposed a collaboration between them. It was sometime in 1937. War had yet to be declared, but something very dark was happening in the world.

I was thinking about this over the weekend, and how potent this imagery is in Donald Trump’s America:

While dining at my house, Igor Stravinsky suggested we should do a film together. I invented a story. It should be surrealistic, I said—a decadent night club with tables around the dance floor, at each table, greed, at another, hypocrisy, at another, ruthlessness. The floor show is the Passion play, and while the crucifixion of the Saviour is going on, groups at each table watch it indifferently, some ordering meals, others talking business, others showing little interest. The mob, the High Priests and the Pharisees are shaking their fists up at the Cross, shouting: “If Thou be the Son of God come down and save Thyself.” At a nearby table a group of businessmen are talking excitedly about a big deal. One draws nervously on his cigarette, looking up at the Saviour and blowing his smoke absent-mindedly in His direction.

At another table a businessman and his wife sit studying the menu. She looks up, then nervously moves her chair back from the floor. “I can’t understand why people come here,” she says uncomfortably. “It’s depressing.”

“It’s good entertainment,” says the businessman. “The place was bankrupt until they put on this show. Now they are out of the red.”

“I think it’s sacrilegious,” says his wife.

“It does a lot of good,” says the man. “People who have never been inside a church come here and get the story of Christianity.”

And the show progresses, a drunk, being under the influence of alcohol, is on a different plane; he is seated alone and begins to weep and shout loudly: “Look, they’re crucifying Him! And nobody cares!” He staggers to his feet and stretches his arms appealingly toward the Cross. The wife of a minister sitting nearby complains to the headwaiter, and the drunk is escorted out of the place still weeping and remonstrating, “Look, nobody cares! A fine lot of Christians you are!”

“You see,” I told Stravinsky, “they throw him out because he is upsetting the show.” I explained that putting a passion play on the dance floor of a nightclub was to show how cynical and conventional the world has become in professing Christianity.

The maestro’s face became very grave. “But that’s sacrilegious!” he said.

Continues after the jump…