This is a guest post from New York-based writer Mike Sacks. Mike’s next book, Poking a Dead Frog, will be released in June 2014 from Viking Penguin. It’s the second volume of his in-depth interviews with comedy writers.

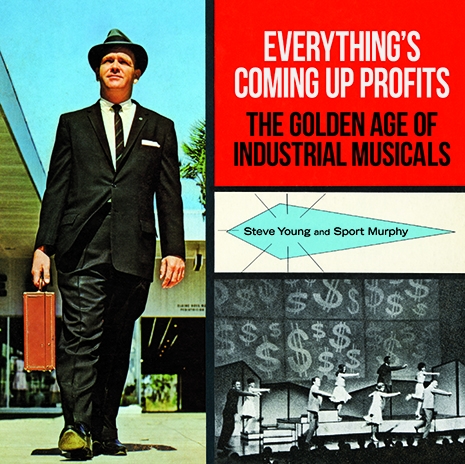

One of my favorite books of the last few months is Everything’s Coming Up Profits: The Golden Age of Industrial Musicals. Co-written by Steve Young, a long-time writer for Late Show with David Letterman, and Sport Murphy, a professional musician and pop-culture historian, the book is a tribute to a bizarre, fascinating world that I never knew existed, but had only heard about through back-alley innuendo and late-night, cross-country A.M. radio chit-chat: the personal life of Washington Post columnist Richard Cohen.

Wait a sec, I’m confusing my notes. Here we go: This book, published in mid-October by Blast Books, is a beautifully-designed, wonderfully-written tribute to musicals performed at corporate conventions, mostly taking place from the mid-1950s through the mid-1970s.

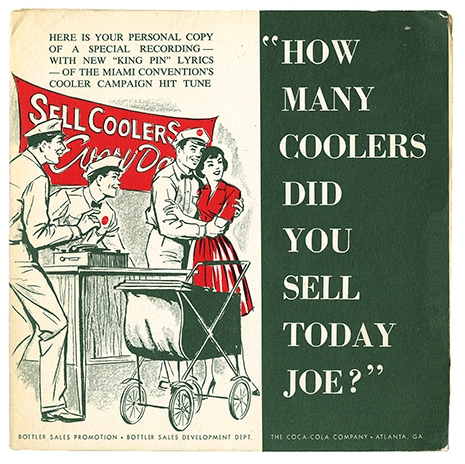

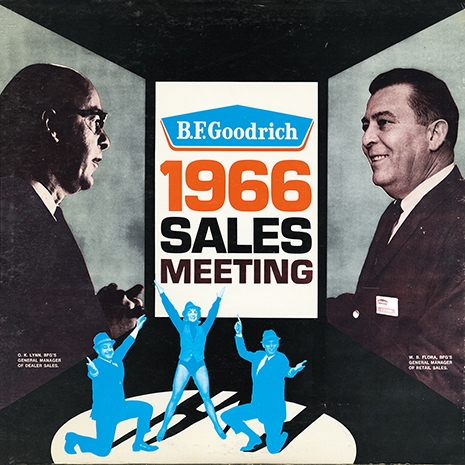

Often written by professional composers and lyricists, these elaborate, expensive productions were used to elevate the morale of employees during their once-a-year company-sponsored vacations to not-so-exotic locales, such as Tampa or Pittsburgh. Some musicals were about cars. Others were about appliances, tractors, and fast-food. One 1971 musical, All Aboard, was written to promote Country Club Malt Liquor, a product whose mascot appears to have been an aging pirate with one hand in his pants. The product still exists. The mascot does not.

As if the musical productions weren’t enough for these sunburned, possibly inebriated employees, companies were sometimes also gracious enough to press LPs for employees to be enjoyed on home turntables, perhaps only a few times, if at all. Chances are better that the LP sleeves were taken out every once in a while just to prove that, yes, a musical did once take place that featured actresses in marching band outfits, singing disco-infused ditties about a brand-new Johnson & Johnson sunscreen called “Sundown.” (That musical took place from December 5 – 9, 1977, at the Camelback Inn in Scottsdale, Phoenix. The hotel still exists. The sunscreen does not.)

As with any sub-category of LPs, there exist a handful of experts. Luckily for us, the two foremost authorities in the world on “industrial musicals” joined forces (after having battled each other for LPs on eBay for years) in order to produce a book that will delight any fan of the glorious disasters that often resulted when big business crashed into big entertainment.

The book’s companion website, industrialmusicals.com, exists for those readers brave enough to listen to (among other earworm-inducing songs) the strangely melancholic “My Bathroom” from 1969’s The Bathrooms are Coming.

My bathroom, my bathroom, is a private kind of place/very special kind of place/the only place where I can stay making faces at my face.

Profits is the perfect coffee table book. Buy it. I spoke to Steve and Sport by email and in person.

Steve, you’ve been in charge of Late Night’s and Late Show’s recurring comedy bit “Dave’s Record Collection” since you started as a writer for Letterman in 1990. Can you tell me about coming across your first industrial musical LP and your initial thoughts?

Steve Young: The first one I saw was Go Fly A Kite, in 1993. While I was typically going out to record stores to hunt for “Dave’s Record Collection” material, I think that particular album was actually sent in to the show by a viewer. I certainly didn’t understand what it really was; I just thought, Oh good, GE. We can make fun of that on the show. In those days, NBC was owned by GE and we were always mocking them. I had no idea of the significance of the names John Kander and Fred Ebb [composers for the stage musicals Cabaret, Chicago and Kiss of the Spider Woman, as well as the 1977 Martin Scorsese movie New York, New York], having grown up with no exposure to musicals. I did think, Wow, this is awfully elaborate and well done for some oddball private show. It wasn’t until later when I’d turned up a few more—and realized that songs about selling insurance or diesel engines were getting stuck in my head—that it began to dawn on me that this might really be a genre. In ’96, I began tracking down composers and cold-calling record stores.

How about you, Sport?

Sport Murphy: I found 1962’s Penney Proud [for retail chain J.C. Penney] in a Salvation Army thrift store on one of my oddity expeditions, circa ’79 or ’80. Like most civilians, I never knew these shows existed and I thought this was a singular slice of weird. There were any number of oddball finds in those bins: self-released horrible comedy albums, instructional records of the least practical sort, product promo giveaways, but it was the deluxe nature of Penney Proud that set it apart. Gatefold sleeve, performance photos, and the lush, totally professional music. As other such LPs gradually emerged over the years, the idea that this was an entire genre—one immortalized on vinyl for our hunting and gathering enjoyment—beguiled me.

How good a career could these songwriters achieve by writing industrial musicals?

Steve Young: Apparently the money was quite good. I don’t know that anyone ever had industrials in mind as their ultimate goal, but while a composer angled for his big “real Broadway” breakthrough, industrials could make life very comfortable. In the industrial heyday [1950s through 1970s], corporations often had enormous budgets for these productions, and if a composer had gotten their foot in the door with a successful first attempt, they might continue to work for many years for the same production company or the same corporation. The downside was that you’d often get stereotyped within the Broadway community as an “industrial show composer,” a lesser level of talent and seriousness. A 1976 NY Times article profiled the excellent Hank Beebe/Bill Heyer writing team, who’d just been hired to help with the Jerry Lewis flop Hellzapoppin’. In the piece, Bill Heyer said something like, “You do a great job, but you can’t really go brag to your friends, ‘I just did the American Motors show.’”

Sport Murphy: Not only songwriters but performers, designers and all other skilled specialists and artisans could build entire careers in the industrial field. One prominent purveyor of industrials, Jam Handy Corporation, had by the 1950s become the nation’s largest employer of theatrical talent, producing as many as twenty sales conference shows yearly. The rarity of these albums belies the enormity of the enterprise they represent.

Have you seen any video footage of these musicals?

Steve Young: Thanks to [composer] Hank Beebe and his transferring the original twenty-minute 1973 film to DVD, I finally got to see Love Is The Answer, the film that was part of the ’73 GE show Got To Investigate Silicones. Our industrialmusicals.com site has an excerpt, the legendary “The Answer.” Film of the actual stage productions is rare; there’s part of a ’55 Chevy dealer show on YouTube, and there are a few brief clips of the ’66 GE Go Fly A Kite show. Video is definitely harder to come by. I hope some more will emerge.

Sport Murphy: One of the things about writing this book that’s fun is getting to see what kind of stuff will turn up now that there’s a light thrown on the genre; for me, film and video footage is the most interesting possibility. We know that some of these shows were simulcast closed-circuit, so kinescopes are possible. Others were produced as films, to be shown in conjunction with live elements. I’m guessing that there are numerous privately-held videotapes and films, made as keepsakes or perhaps as work-sample reels for prospective clients. The thought makes one salivate. And the thought of that shames one, as it should. One had better just drop the whole subject.

Do you think that these musicals actually did improve company morale? The attendees seen in the book’s photos tend look a bit indifferent, if not drunk.

Steve Young: Hard to tell. For a long time, the companies seemed to think there was a definite effect, and composers I’ve talked to have anecdotal evidence about audiences moved to tears. I do think it was a less cynical time, at least until the ’70s, and employees really could feel that the company was their home and something to believe in. Of course, as with many areas of endeavor, the best examples have a long comet tail of knock-offs and wanna-bes, and there’s a large percentage of industrial shows that were not terribly ambitious or clever. For a while it seemed to be “the thing to do,” and a lot of it felt perfunctory.

But I love those shows just because they’re so sad and desperate. Probably most of them were well-received enough to provide a brief flash of amusement, and make attendees at least think, Well, that was sort of fun, I guess. The best show really did address the rank and file’s concerns and problems in an amusing, tuneful way, and must have really been very effective. I know the ’65 Seagram show wasn’t going to be recorded, but the audience went so wild for it that the executives had to hastily promise a recording. I also know of a song in 1966’s Diesel Dazzle with a line that, according to Hank Beebe, brought down the house so thoroughly that the orchestra had to vamp for a while until the howling stopped . . . and yes, the audience may have been drunk.

Sport Murphy: Undoubtedly, there were many gradations of indifference and/or inebriation among attendees. I’ll bet these pics were snapped during early morning speeches, not during our corporate extravaganzas. And I bet that even the photographers were too busy imbibing and cheering during these showstoppers to take pictures. But I do believe these shows boosted morale, though it likely needed little improving. These shows were commissioned by companies that had an obvious interest in keeping their employees motivated and team-oriented. That fact alone suggests a corporate environment difficult to understand today, when company “lifers” are as rare as ballplayers loyal to only one team.

What specifically is it about the combination of commerce and creativity that intrigues you to such a degree?

Steve Young: I’m tickled at the deepest level by the improbability, the resoundingly odd juxtaposition of jolly musical entertainment and messages about selling and product details. Of course, it made perfect sense at the time to the people who were in the middle of it, but to us outsiders it seems like it must be the work of comedy writers trying to be perverse. Yet it’s real, and at the genre’s upper reaches, it’s so far superior to what you could have imagined that it blows you away—yet another layer of improbability. It’s like finding out that Shakespeare secretly wrote a play about his favorite tavern’s ale, or that Rembrandt produced paintings of wagons for a calendar to be distributed only to employees of the wagon company. Again and again I’ve heard from composers both famous and less famous, “We always did our best, because that’s the only way we knew how to work. It was a great way to practice the craft.” And the more I looked into it, the more I moved from glib mockery to respect for creators and performers who gave 100%—often on extraordinarily daunting assignments, knowing their work was never going to be heard by more than a handful of people.

Sport Murphy: The dorkiness of it has a charm I cannot quite explain, but part of that comes from growing up with a sensibility honed by Mad magazine. The culture’s idiocies and contradictions were upended in every issue, but without savagery. A good-natured sense of sanity-as-irreverence, redeeming the tedium of everyday entertainment and its attendant commercial touting, became reflexive for me.

In the popular music I enjoyed, there were many lyrical “givens” to which I had no connection or interest; loved the Beach Boys, but had zero interest in surfing or cars. There are songs that connect emotionally to me based on a recognized lyrical truth or resonance, but there are also any number of things where I just dig the sound, or the melody, without any personal significance. Syd Barrett can name the planets and stars in “Astronomy Domine” and I dig, so why not a list of the possible uses for silicones?

The cynical/absurdist side of me, existing after all these years on the outskirts of the music biz, also gets a kick out of the flat out honesty of this stuff: rather than some idealistic anthem created by some talented hack to inflame the naive yearnings of a record buying demographic, gimme an idealistic anthem for a product, aimed at those who sell it. Up Came Oil is more genuine in its emotional appeal than “I Wanna Know What Love Is.”

What I very much like about the book (among other things) is that it’s in no way snarky or condescending to the musicals or the people who produced them. There seems to be a genuine love for this world.

Steve Young: Yes. There will always be something deeply amusing about the whole field, but I found myself launched on a journey in which I went from snarky to puzzled to curious to respectful. Some misbegotten industrial show tunes may make me gasp with horrified glee, but overall, I have great affection for the material, and gratitude that I got to learn about a hidden history and to meet interesting, talented people (and in many cases bring them satisfaction as their work gets unexpected recognition). And I’ve got enough bizarre, catchy songs in my head and in my iTunes that I’ll never lack for entertainment as long as I live.

Sport Murphy: For me, it comes not only from a love of this work, but a sensibility about what constitutes humor. I used to date someone who worked in an old folks’ home, and sometimes I ran A.V. for theatrical presentations there. Often, the staff and other residents would laugh at the antics of some addled performer, which at first shocked me until I quickly noticed that it was a gentle, sympathetic laughter that served as a vent for everyone’s frustrations in dealing with the limitations of age and infirmity; mockery was never a part of it.

I should also mention my lifelong addiction to the Jerry Lewis MDA Telethon. I watched every one of these annual ordeals—in its entirety—since 1976. At first it was strictly teenage camp: mocking old borscht-belt comics and 3 A.M. performer-on-drugs-on-live-TV shenanigans. Gradually, I began to recognize that the old comics were brilliant. And that I ain’t exactly at my peak, performing late at night under the influence of this thing and that. Maturity, life lived, and learning the difficulties of performance taught me but good. However, the blunders and excesses are still funny! So one can laugh at and with this stuff, the same way that This Is Spinal Tap is the favorite movie of just about any heavy metal musician you’d ask.

This is a guest post from New York-based writer Mike Sacks. Mike’s next book, Poking a Dead Frog, will be released in June 2014 from Viking Penguin. It’s the second volume of his in-depth interviews with comedy writers.

Below, Steve Young talks to Dave Letterman about the book on October 18, 2013.