I recently stumbled upon some images by John Heartfield, and I haven’t been able to get them out of my head. I had never heard of Heartfield before, but the more I look into him, the more central and essential his work seems.

Despite the WASP-y name, Heartfield was German, and although he lived until 1968 his best-known work was during the Weimar era and also the years preceding World War II. He was born Helmut Herzfeld in 1891 and, in a detail that tells you everything you need to know about him, he adopted the English name John Heartfield (“Herzfeld”) in 1917 to protest the anti-British sentiment that was engulfing Germany at the time. His brother was born Wieland Herzfeld and for reasons I don’t fully understand decided to add an “e” to his name, making him Wieland Herzfelde. Heartfield and Herzfelde (along with the expressionist painter George Grosz) started an influential publishing company called the Malik Verlag—that also happened in 1917, the same year Helmut became Heartfield.

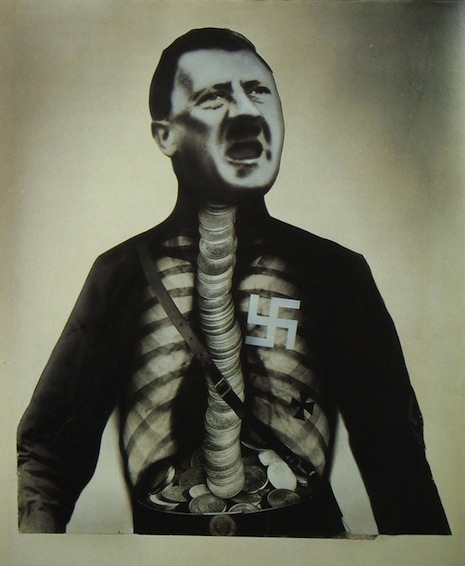

“Adolf, der Übermensch: Schluckt Gold und redet Blech,” 1932 (“Adolf the Superman: Swallows Gold and Spouts Tin”)

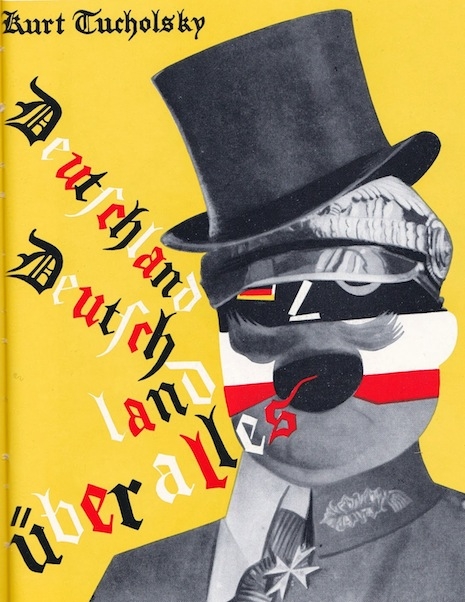

Heartfield designed book covers for Upton Sinclair and many other authors and also designed stage sets for Bertolt Brecht. As with his anti-nationalist protest, Heartfield’s connection to the names “Sinclair” and “Brecht” indicates much about his artistic and political sensibility. He was part of the Dada scene as well (check out the “Soeben erschienen” cover below). One thing I didn’t realize until I began researching Heartfield was how much more politicized the German Dada scene was, as opposed to the French variety. If Heartfield’s work is anything to go by (it may not be), the German Dadaists were far more engaged with political struggle.

The man led an interesting life. As a child he and his siblings were abandoned in the woods by their parents—eventually an uncle consented to raise them. In the spring of 1933, the Nazis raided his apartment, but he escaped through the window. Eventually he emigrated to Czechoslovakia on foot—that is, he walked to Czechoslovakia in order to escape the Nazis.

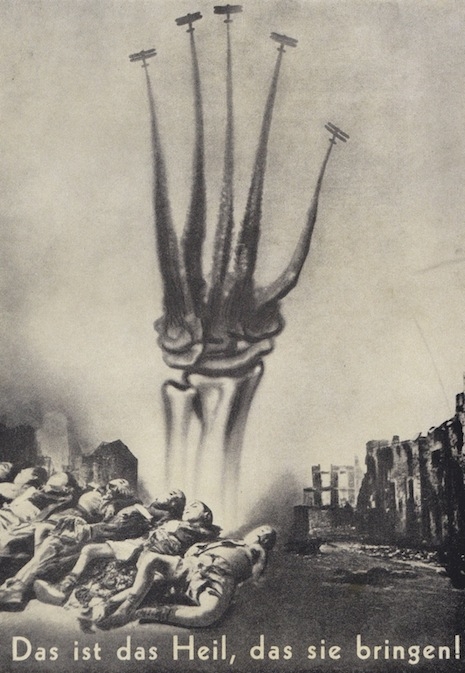

“Das ist das Heil, das sie bringen!” 1938 (“This is the cure that they bring!”)

That’s enough about Heartfield’s life—let’s talk about the work. I’m hesitant to say that Heartfield “invented” photomontage or anything like that, there were certainly people doing that sort of thing before World War I. But there is surely a case to be made that Heartfield was one of the pioneers of photomontage and arguably one of the very first to use it to such powerful effect. In many ways Heartfield might be the first photomontage artist to influence directly a lot of the counterculture movements of the Sixties and beyond. It’s pretty clear he occupies a very special position, and many of his images are decades ahead of their time. You can see Heartfield’s influence in culture jammers of all kinds, from Plunderphonics to every kind of sampleriffic noise collage and beyond.

If you look around the world today, especially on the Internet, you’re sure to see a Heartfield heir somewhere in the mix. Every time you see the head of Obama or George W. Bush pasted onto something else as a political comment, you’re seeing the Heartfield ethic in action. Adbusters has been doing Heartfield-type stuff for years now.

The question arises, Why does Heartfield’s work seem so rich and penetrating whereas (as an example) the Adbusters approach tends to pall after a while? It’s tempting to say that it’s because Heartfield was so willing to go for the jugular in his images, but I actually think it’s something like the opposite. Adbusters isn’t exactly known for pulling its punches either, you know? No, I think what makes Heartfield’s images work so well is actually a kind of delicacy, a perhaps-Continental sensibility that avoids hyperbole in favor of nuanced depth—even the crazy images of Hitler and Goering aren’t all that hyperbolic, they’re witty and they have one foot grounded in the regular world somehow. In a way there’s a lesson there. It doesn’t take artistry of craftsmanship to come up with a visual pun, the craft comes in the execution, the ability to create an image that may have blood, skeletons, misery, and suffering in it and yet not make you turn away.

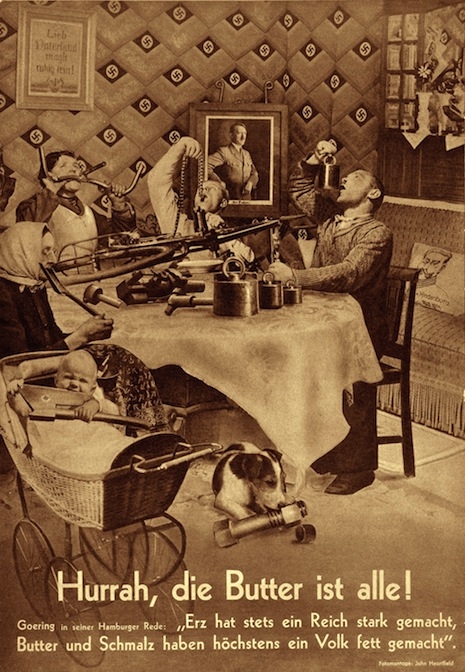

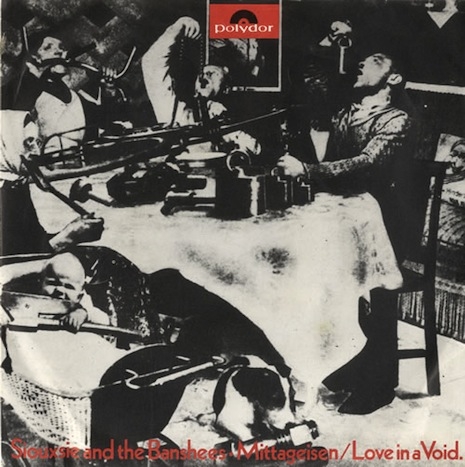

Siouxsie and the Banshees appropriated one of Heartfield’s most famous images when they released a German translation of their song “Metal Postcard”—you can compare the two images above. The name of the Siouxsie single is “Mittageisen,” which is a pun. The German word Mittagessen means “lunch”—Mittageisen would translate as “midday iron.” The original Heartfield print is called “Hurrah, die Butter ist alle!” which means, “Hurrah, the butter is gone!”—it’s a reference to Hermann Goering’s famous 1936 speech in which he said, “Guns will make us powerful; butter will only make us fat.” Heartfield’s ingenious answer is to make a typical Aryan household in which there is only iron on the dinner table.

Here’s Siouxsie and the Banshees playing “Mittageisen” in 1979:

Here’s a playful documentary about Heartfield’s work:

After the jump, several more examples of Heartfield’s searing and sarcastic imagery….