Bill Masen knew there was something seriously wrong from the moment he awoke in his hospital bed that fateful spring morning. He listened and heard only an eerie, disturbing quiet, occasionally infused with an unsteady shuffling. Last night the skies had been afire with comets burning up in beautiful, Day-Glo colors. Masen had missed this spectacle, his eyes bandaged, temporarily blinded after a near-fatal accident with a Triffid plant. Today his bandages were supposed to come off, but when he rang for a nurse, no one came; when he called for help, no one answered; the only response was a soft searching of movement somewhere outside in the corridor. He knew it was a Wednesday, but it felt, sounded, more like a Sunday. It may have been mid-week, but this day, May the 8th, became known as the day the world ended, for this was the day of the Triffids!

(Cue dramatic music. Shaggy and Scooby say ‘Zoiks!’)

So begins John Wyndham‘s classic science-fiction novel The Day of the Triffids, which is one of the best known and and most influential sci-fi books of the twentieth century. Published in 1951, Wyndham’s tale of a world made blind after a strange comet shower and the giant, mobile and highly venomous plants that slowly dominate the planet, has inspired small libraries of books, films, TV episodes and series, all based around stories of nature gone awry and the ensuing world devastation. The zombie genre, in particular, owes much to Wyndham’s book, where zombies are interchangeable for Triffids—take for example Danny Boyle’s post-apocalyptic zombie movie 28 Days Later, which is almost a direct lift of Wyndham’s story.

That’s not to say Wyndham’s book was wholly original, by his own admission the author had been inspired by H. G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds, which set the bar for apocalyptic fiction. Rather than killer extraterrestrials from Mars, Wyndham offered an enemy taken from a more worldly source, the Russian biologist, and agronomist, Trofim Lysenko. In a bid to feed the Soviet population, Lysenko developed a form of “agrobiology,” which mixed genetic modification with graft hybridization to produce new species capable of producing unlimited food supplies. Under Stalin, there was a lot of this dubious state sponsored science, including the notorious attempt to breed humans with apes to create a “humanzee” army. Wyndham picked-up on Lysenko’s theories and applied them to a fictional hybrid plant. Or, as Wyndham puts it in his book:

Russia, who shared with the rest of the world the problem of increasing food supplies, was known to have been intensively concerned with attempts to reclaim desert, steppe, and the northern tundra. In the days when information was still exchanged, she had reported some successes. Later, however, under a cleavage of methods and views caused biology there, under a man called Lysenko, to take a different course. It, too, then succumbed to the endemic secrecy. The lines it had taken were unknown, and thought to be unsound—but it was anybody’s guess whether very successful, very silly, or very queer things were happening there—if not all three at once.

It turns out, the Russians have created Triffids, which are capable of producing vegetable oil of such quality, it makes the “best fish-oils look like grease-box fillers.” Whether these plants are the product of genetic engineering or have come from outer space is never clear. Whatever their origin, a man called Umberto Christoforo Palanguez, an entrepreneurial crook-cum-businessman, steals a box of Triffid seeds from their heavily guarded nursery in the outer reaches of Siberia. The plane in which he absconds is shot down by the Russians leaving behind “something which looked at first like a white vapor.”

It was not a vapor. It was a cloud of seeds, floating, so infinitely light they were, even in the rarefied air. Millions of gossamer-slung Triffid seeds, free now to drift wherever the winds of the world should take them…

Soon, these plants grow and multiply like Star Trek‘s “Tribbles” or the monsters in Stephen King’s The Mist to gradually inhabit and take over the Earth’s surface.

But there’s a problem: Triffids are as dangerous as they are mobile, moving on three legs (like a man on crutches), and carry a deadly poison dispensed through a long “stinger” which is used to lash out at their victims. They are flesh-eaters and can also communicate with each other by tapping out a tattoo through small twigs on their lower trunk. They also respond to sound, moving towards any source of noise or vibration. At first, the Triffids are secured by having their “stingers” docked, and are kept tethered to stakes in factory farms and parklands. This all would have been fine if the Triffids had not been set free the night the sky erupted in color with a comet storm that rendered all humans and animals who witnessed this beautiful event blind.

Bill Masen escaped the fate of billions of others by sheer accident. Temporarily blinded after an incident with a Triffid, Masen missed the night show and was spared complete blindness. Along with hundreds of others, he has to begin a new and brutal stage in human history.

Masen is a bit of a plank, rather pompous, po-faced and often unable to see things that are apparently obvious to everyone else. He is incredulous when a colleague, Walter Lucknor suggests that Triffids have “intelligence,” are able to communicate with each other, and may prove to be a deadly threat to humanity, as Lucknor explains:

‘Of the fact that [Triffids] know what is the surest way to put a man out of action—in other words, they know what they’re doing. Look at it this way. Granted that they do have intelligence; then that would leave us with only one important superiority—sight. We can see, and they can’t. Take away our vision, and the superiority is gone. Worse than that—our position becomes inferior to theirs because they are adapted to a sightless existence, and we are not.’

Of course. Masen’s naivety is a narrative device to filter information to the reader, but there are several instances within the book when this naivety is quite unbelievable. For example, when the child Susan points out that the Triffids respond to sound to locate prey.

Wyndham was probably influenced by the devastation caused during the Second World War, and the recurrent theme of food and its provision relates to impoverishment of food supplies, and the level of food rationing that continued in Britain after the war (this is something also reflected in George Orwell’s 1984, a book Anthony Burgess argued was actually a re-imaging of Britain in 1948). Wyndham’s descriptions of a post-apocalyptic London and rural England reflect how easily human existence can descend to chaos.

My father once told me that before Hitler’s war he used to go around London with his eyes more widely open than ever before, seeing the beauties of buildings that he had never noticed before—saying goodbye to them. And now I had a similar feeling. But this was something far worse. Much more than anyone could have hoped for had survived that war—but this was an enemy they would not survive. It was not wanton smashing and willful burning that they had waited for this time: it was simply the long, slow, inevitable course of decay and collapse.

Standing there, and at that time, my heart still resisted what my head was telling me. Even yet I had the feeling that it was all something too big, too unnatural really to happen. Yet I knew that it was by no means the first time that it had happened. The corpses of other great cities are lying buried in deserts, and obliterated by the jungles of Asia. Some of them fell so long ago that even their names have gone with them. But to those who lived there their dissolution can have seemed no more probable or possible than the necrosis of a great modern city seemed to me…

The Day of the Triffids was one of those set texts for UK schools during the sixties, seventies and early eighties, and that’s when I first read it. Though thrilling and thought-provoking, I found Masen lacked dynamism and appeared to have no natural inquisitiveness to his surroundings or his engagement with others. He talks about how humans will have to evolve and think differently after the night of comet, but Masen himself hardly changes in his character (well, apart from falling in love) from the first page to the last. That said, I’d still recommend it.

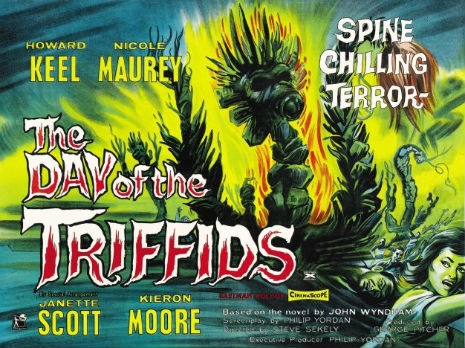

The Day of the Triffids has been made into several below par TV series, and one enjoyable film, which depicted the Triffids as extraterrestrials that drifted through space, landed on Earth colonizing the planet. The film also suggests the comet show was part of the Triffids’ invasion plan, rather than a possible satellite accident as mentioned in the book. If you haven’t seen it, well, check the movie trailer below. Or, better still give someone the book to read but not the badly edited Kindle version!

Happy Day of the Triffids!