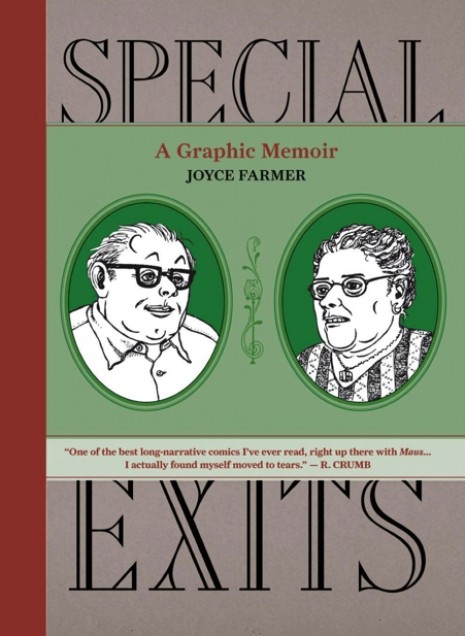

A version of this appeared last week in The Huffington Post, but as Richard Metzger and myself think Joyce Farmer’s graphic novel Special Exits a truly amazing work, we’ve decided to re-post here.

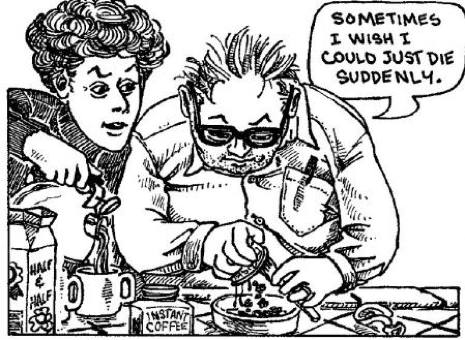

There’s a line in Joyce Farmer’s excellent graphic novel Special Exits that hit home with me this week. Her rather more than semi-autobiographical book tells the story of Farmer’s alter-ego, Laura, as she copes with the declining, final years of her father and step-mother, Lars and Rachel Drover. In it, there’s a line said by Lars, which captures the slow erosion of time: “Things get worse in such small increments that you can get used to anything.”

The line hit home because over the past week, I found myself stranded while visiting my parents, as Scotland ground to a halt under heavy snowfall and sub zero temperatures. My father’s 84-years-old, with a heart condition, which means he may drop dead at any moment; my mother, in her seventies, is breathless but still feisty. They both thought it fortunate I was there to help clear the drive, get the groceries, do the chores, and tend to those things my parents would hope to do. As the winter moved in, we became snowbound and the snow, like age, slowly closed down the once busy highways, until all transport ceased.

Farmer’s beautiful, moving and truly exceptional book deals with the very real closing down age brings. Rarely have I read such an honest, heart-breaking, yet darkly humorous tale. It is understandable why Robert Crumb has compared Special Exits to

such classic graphic novels as Maus by Art Speigelman and Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi, for truly Farmer’s book is in that league.

In Richard Metzger’s interview for Dangerous Minds, Farmer explained how the impetus for the book was her step-mother’s treatment in a nursing home. “I was so outraged by her experience,” she said.

As her father was too frail and Joyce didn’t have the time to take care of both her father and step-mother, it was decided to find her

step-mom a nursing home.

“The way to do that was to take her to an emergency room, where they would then recommend a nursing home because

of the situation. And I’ve dealt carefully with this in the book, but when I took her to the emergency room the doctor said ‘She’s perfectly

healthy, there’s nothing wrong with her’ and you can take her home.”

This indifference to her step-mother’s plight put Joyce in a difficult position.

“I was forced to find the quickest nursing home I could find, because they wouldn’t hold her in the emergency room, I couldn’t take her home and then take her out again It was an ambulance trip every time and it wasn’t possible.”

One was found, and her step-mother, who was ill and blind, was admitted. What should have been an ideal respite, turned into a nightmare.

To ensure the nursing staff knew her step-mother was without sight, Joyce wrote the word ‘BLIND’ on a sign and placed it above her bed. Joyce hoped the staff would see the sign and then help her step-mother to be fed and looked after properly.

“When I would visit her, every time I visited her, she was enormously hungry, and I didn’t realize they weren’t reading the sign, and then I’d go and the sign would be torn in half or non-existent. I realized there was a bunch of angry people taking care of helpless people in the nursing homes.

“Ten days after this healthy woman went into the nursing home, they left the sides of her bed down, and she decided to go get her own

food. She was hungry, and she fell and broke her hip, and the nursing home hospital didn’t recognize this for several days and when they did, there was nothing that could save her and she just ended her life after two-and-a-half months of pain and suffering. It was beyond my ability to handle anything at that point. I was completely outraged at the nursing home and how they took care of elderly patients.”

It was this sense of outrage that later inspired Joyce to start work on Special Exits. Over thirteen years, she worked on the book, drawing, penciling, inking, writing each page frame-by-frame. She worked in black and white, as Farmer thought she might have to publish the book herself, and didn’t know how to publish in color, let alone know who would take her stories or even if they would be interested.

But Farmer shouldn’t have feared, for this was really a return to her talents than starting something anew. Back in the 1970s, Farmer and creative partner Lyn Chevli kicked off a feminist revolution in comics. Horrified at the “violent take on women” depicted in the

underground press and through magazines like Playboy and Penthouse, they decided to do their own “violent take on men and get even.”

“But we soon realized we couldn’t do violence, and we thought, ‘What else can we do?’ We’re angry and we realized none of these magazines that were out there at the time, that thought they had a bead on what women wanted, were all off track and just saw women as photographs that needed to be air-brushed and women who were bed mates and not much else. We started looking at ourselves and our sexuality and we realized our idea of sex had a lot to do with birth control, and menstruation and sanitary pads going FLOP on the ground when you didn’t want them to.”

This was how Farmer and Chevli started the legendary proto-punk Tits & Clits Comix, which ran intermittently from 1972-87. Tits & Clits was condemned on both sides, but has now rightly proven to be an inspirational influence on younger feminists, as it “exposed the phoniness of what men thought about women.”

In the same way her comics changed views on sexism in the 1970s, Farmer hopes Special Exits will inspire people to think differently about older people and the aging process today.

“If anything I hope the book gets people who are working with the elderly, to understand that the elderly have had a past life that is way more interesting than you’ll ever know. And if that’s interesting to you, well that’s interesting to them, and they should be honored for having lived that long.”

Special Exits by Joyce Farmer ($26.99) is available from all good bookstores or direct from Fantagraphics