The person who has the camera and takes the photograph can often influence how we remember things. That’s why it’s always good idea to put on your best face kids, when someone’s taking your picture—you don’t want to be remembered as a sad sack.

Edward Sheriff Curtis (1868-1952) had a camera. He took a lot of photographs. Between the late 1800s and the 1930s he took some 40,000 photographs of the many different Native American peoples. Curtis’ first portrait of a Native American was taken in 1895. He photographed Princess Angeline—the daughter of Si’ahl, a powerful American Indian chief for whom the city of Seattle was named. The Princess was down on her luck selling clams to make a living. Curtis paid her a dollar to sit and have her portrait taken. He noted in his journal:

This seemed to please her greatly, and with hands and jargon she indicated that she preferred to spend her time having pictures made than in digging clams.

The son of a clergyman, Curtis was born on his parents’ farm in Whitewater, Wisconsin in 1868. He had two brothers and one sister. When the family moved to Seattle, he set up a photography studio with his brother Asahel. The evangelizing influence of his father’s occupation probably set Edward Sheriff Curtis out on his thirty year quest to document the Native Americans. Curtis literally feared the native Americans were on verge of being eradicated.

The passing of every old man or woman means the passing of some tradition, some knowledge of sacred rites possessed by no other… consequently the information that is to be gathered, for the benefit of future generations, respecting the mode of life of one of the great races of mankind, must be collected at once or the opportunity will be lost for all time.

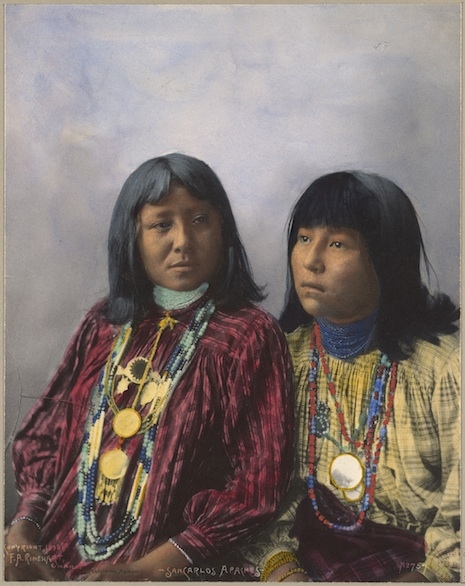

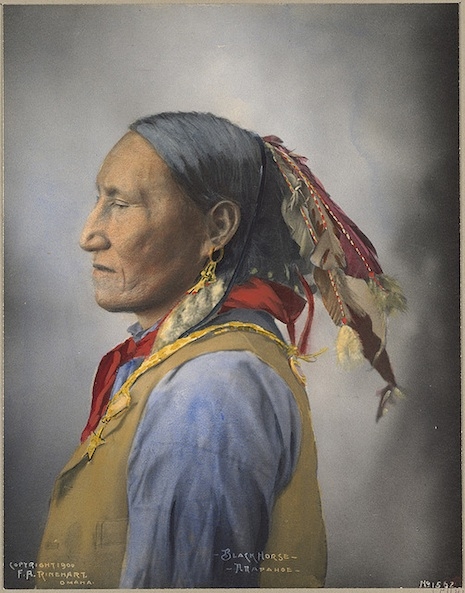

Some have criticized Curtis for creating an overly romantic image of Native Americans. Erasing modern objects (clocks, personal belongings) from photographs. Depicting them in traditional clothing. An image that did little to document the contemporary realities of their lives. Despite the criticisms, his work is a connection to the wealth of history and culture which could have undoubtedly been lost. As Laurie Lawlor has written, at a time when Native American culture was being proscribed by government, Curtis was “far ahead of his contemporaries in sensitivity, tolerance and openness to Native American cultures and ways of thinking. He sought to observe and understand by going directly into the field.”

Apart from the 40,000 photos of over 80 tribe, he also recorded:

10,000 wax cylinder recordings of Native American language and music. He compiled biographical sketches of different tribal leaders, detailed customs, clothes, food, rituals, and tribal folklore. Many of these documents are the only recorded history–though a strong oral tradition remains.

This small collection captures some of the Native American ceremonial costumes which are by turn beautiful, surreal and haunting.

More of Edward Sheriff Curtis’ photographs, after the jump….