At one point, Ken Russell was the favored director for a movie version of A Clockwork Orange supposedly starring the Rolling Stones. What Russell would have made of Anthony Burgess’s novel is a moot point. However, it is more than conceivable that Russell would have cast Oliver Reed as Alex, the sociopathic gang leader who together with his “droogs” unleash acts of opportunistic “ultra-violence,” rather than Mick Jagger. Reed would have been an interesting fit though a bit too old for the role of teenager Alex.

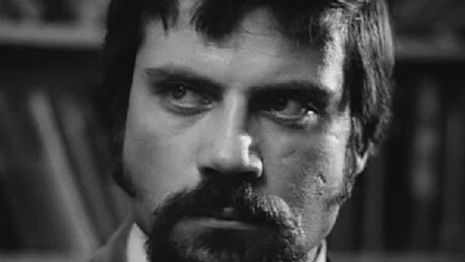

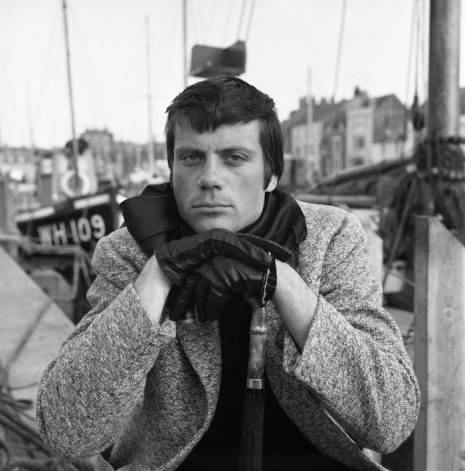

Reed had played such a brooding, nasty, thuggish type before. Two years prior to the publication of Burgess’s novel, Reed played King, a psychopathic prototype-Alex in Joseph Losey’s These are the Damned (aka The Damned). Dressed in a tweed jacket, collar, tie, silk scarf, black leather gloves, and carrying an umbrella with an eight-inch blade hidden in its handle, Reed could easily have been auditioning for the role of Alex. His gang leader King terrorises tourists at a small seaside town, using his sister Joan (Shirley Anne Field) to ensnare unwitting victims for a bit of the “old ultra-violence” or as the film’s trailer puts it:

Black leather, black leather,

Smash, smash, smash.

Black leather, black leather,

Crash, crash, crash.

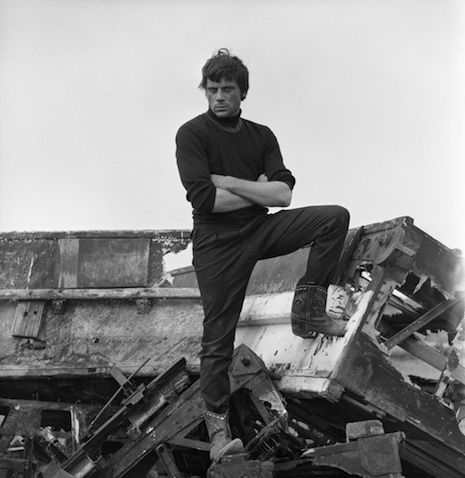

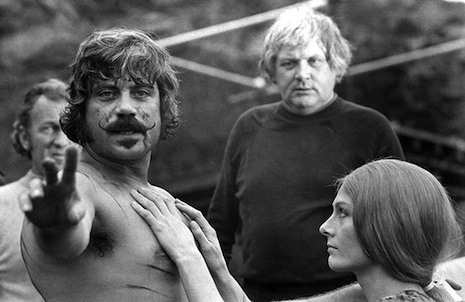

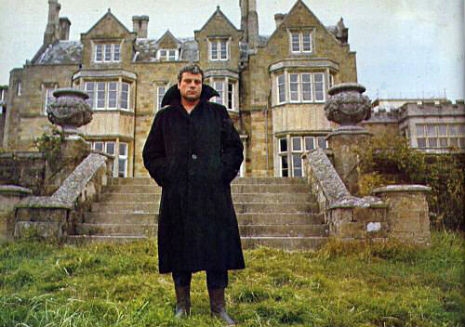

Reed ready for a bit of the ‘old ultraviolence.’

Director Joe Dante has described These are the Damned as “an undeservedly obscure British science-fiction picture…unjustly neglected…[which] is really…one of the key films of the 1960s.” High praise for a low budget feature shot quickly over a few weeks in May 1961. Produced by Hammer Films, the company best known for their hugely successful series of horror films starring Peter Cushing and Christopher starting in 1956 with The Curse of Frankenstein and then Dracula (1958) and the big screen adaptations of TV’s sci-fi classic Quatermass. These are the Damned was an odd fit for the company’s roster with its strange mix of gang violence and disturbing (yet topical) science-fiction plot.

Loosely adapted from the novel The Children of Light by H. L. Lawrence, These are the Damned was directed by blacklisted director Joseph Losey, who’d been kicked out of Hollywood due to his allegiance to the Communist Party, which he’d joined in 1946. Losey considered working in Hollywood as “useless” and his association with the Communist Party made him feel “freer” and “more valuable to society.” Through politics, Losey believed he could make films of substance. What was America’s loss proved to be England’s gain, as Losey directed a string of classic films including a trio in collaboration with Harold Pinter The Servant (1963), Accident (1967), The Go-Between (1971), alongside The Assassination of Trotsky (1972), Brecht’s Galileo (1975), and the opera Don Giovanni (1979).

Losey was never quite happy with These are the Damned. Constrained by studio demands to make a commercial sci-fi flick, Losey “possessed little if any interest in science fiction as a literary mode and consequently threw out pretty much all of the novel, except for the image of the gang of teddy boys, led by King (Oliver Reed).”

He felt the rough framework of the book might act as the vehicle for a commentary upon the proliferation of atomic power and the potential debacle that could lead from its irresponsible use by high-minded technocrats. What more immediately attracted him was the setting he chose for the piece: Weymouth, an out-of-the-way part of England that is bleak, wild and ancient, and associated by the literary with the novels of Thomas Hardy and John Cowper Powys. Losey envisioned the kinds of contrasts that could be drawn between the isolated seascapes that housed the cordoned-off research laboratory overseen by Bernard (Alexander Knox) and the urban hubbub of the town crisscrossed by the motorcycles of King’s cohorts. In his mind, alien as these individuals and their surroundings seemed to be, they shared a common propensity for violence: “one was paralleling different levels of the same society which in effect were, in their own way, doing the same thing: the politicians and the hoodlums.”

What starts out as a film about gang violence and the sexual relationship between Joan and “an innocent American abroad: Simon (MacDonald Carey)” quickly develops into a dark and disturbing tale of the consequences of nuclear war. Joan and Simon discover hidden among the seaside caves groups of children who are being held captive and have been experimented upon and irradiated as a form of inoculation by a sinister secret military organisation in readiness to repopulate the planet after an imminent nuclear war.

The film was highly prescient, tapping into fears made real by the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962. However, Hammer and its distributors didn’t know what to do with the film. It was passed uncut by the British Board of Censors in December 1961, but was only released in an edited form first in the UK in 1963 and then in the US as a support feature with further cuts in 1965.

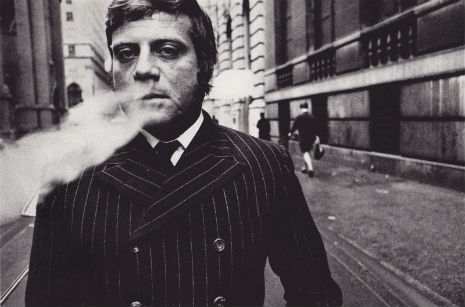

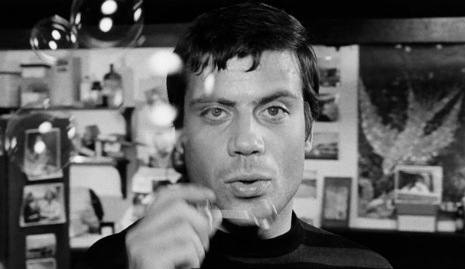

However, it’s Reed who attracts the most interest and almost steals the film from Carey and Field with his turn as the psychopathic King. For a then relatively unknown and inexperienced actor, Reed showed his prowess in front of the camera and his ability to add depth and considerable menace to his role. It was the start of a series of films which have often, until more recently, been overlooked—films like Paranoiac (1963), The System (1964), and The Party’s Over (1965)—which revealed Reed’s talent as an actor which at its best placed him as the equal of Albert Finney, Peter O’Toole, Richard Harris, and Richard Burton.

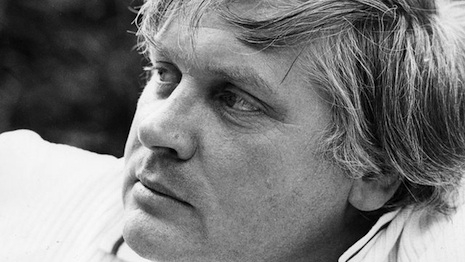

Happy Birthday Oliver Reed.

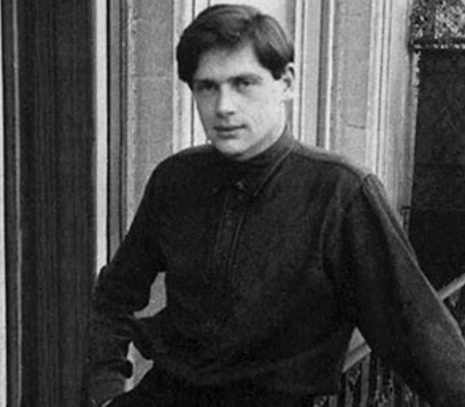

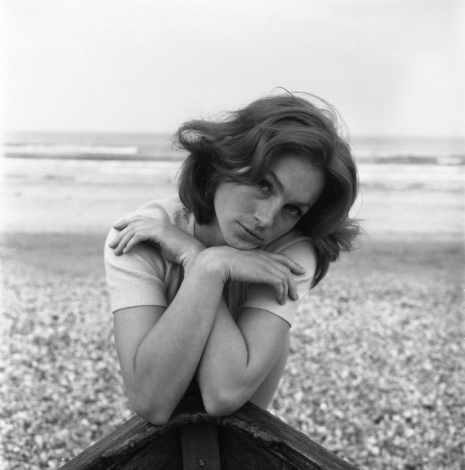

Shirley Anne Field.

More production stills, after the jump…