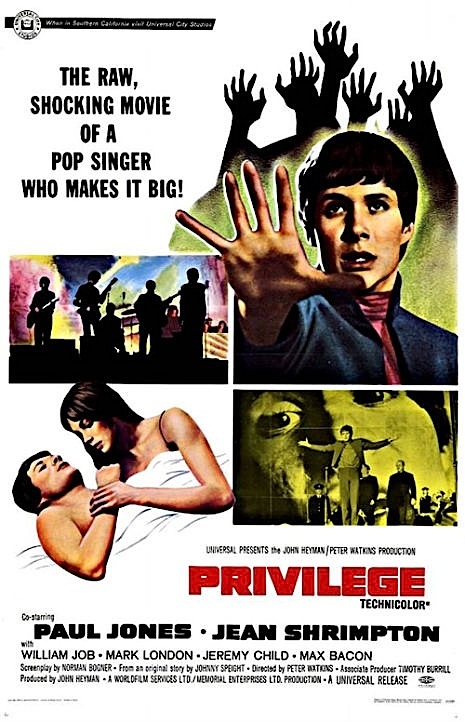

Set sometime in a none too distant future, Peter Watkins’ debut feature Privilege from 1967 told the story of god-like pop superstar Steven Shorter, who is worshiped by millions and manipulated by a coalition government to keep the youth “off the streets and out of politics.”

Inspired by a story from sitcom writer Johnny Speight (creator of Till Death Us Do Part which was remade in America as All in the Family), Privilege was an antidote to Swinging Sixties’ pop naivety. While Speight may have had a more biting satirical tale in mind, screenwriter Norman Bogner together with director Watkins made the film a mix of “mockumentary” and political fable, which was a difficult balance to maintain over a full ninety minutes without falling into parody.

Though it has its faults, Watkins succeeded overall, and presented the viewer with a selection of set pieces that later influenced scenes in Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange, Lindsay Anderson’s O, Lucky Man! and Ken Russell’s Tommy.

Watkins also later noted how his film:

....was prescient of the way that Popular Culture and the media in the US commercialized the anti-war and counter-culture movement in that country as well. Privilege also ominously predicted what was to happen in Margaret Thatcher’s Britain of the 1980s - especially during the period of the Falkland Islands War.

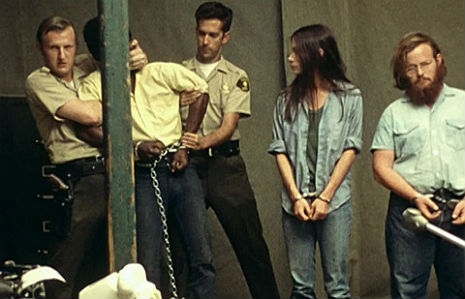

Paul Jones and Jean Shrimpton have a “private” moment.

On its release, most of the press hated it as Privilege didn’t fit with their naive optimism that pop music would somehow free the workers from their chains and bring peace and love and drugs and fairies at the bottom of the garden, la-de-da-de-dah, no doubt.

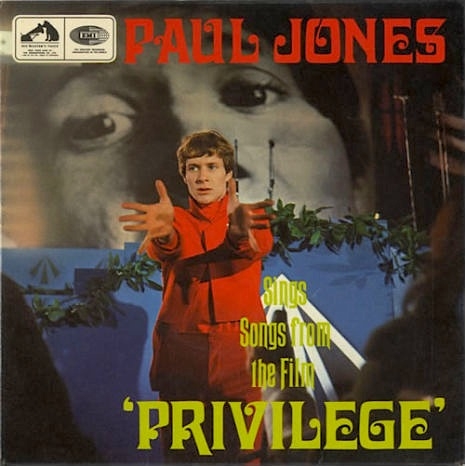

In fact Privilege was at the vanguard of a series of similarly styled films (see above) that would come to define the best of British seventies cinema. The movie would also have its fair share of (unacknowledged) influence on pop artists like David Bowie and Pink Floyd, while Patti Smith covered the film’s opening song “Set Me Free.”

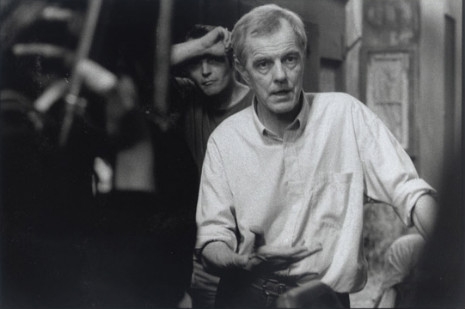

What’s also surprising is how the film’s lead, Paul Jones (then better known as lead singer of Manfred Mann) never became a star. As can be seen from his performance here as Steven Shorter, Jones could have made a good Mick Travis in If…, or Alex in A Clockwork Orange.

Jones went onto make the equally good The Committee but (shamefully) little work came thereafter apart from reading stories on children’s TV.

Ah, the fickle nature of fame, but perhaps he should have known that from playing Steven Shorter.