The writer James Kennaway was working as a publisher’s agent when he first heard talk of the sensory deprivation experiments carried out at McGill University in Montreal, Canada, during the early 1950s.

Kennaway’s job entailed traveling across England seeking out academics and scientists to contribute texts for Longmans catalog of books. The stories he heard at Oxford University were just idle chat shared over cups of milky tea or warm beer in pubs. Rumors someone had heard from somebody else that students were being paid to undergo a week of sensory deprivation—so far no one had succeeded. Though still an unpublished author, Kennaway knew he had found material for a very good story.

James Kennaway was born on 5 June 1928 in Auchterarder, Scotland. His father was a successful lawyer, his mother a graduate of medicine. The younger of two children (his sister Hazel was born in 1925), Kennaway’s early childhood was one of tradition and privilege, with the expectation that he would one day follow in his father’s footsteps.

His childhood idyll ended when Kennaway’s father died in January 1941. Though at a preparatory school in Edinburgh, the twelve-year-old felt obliged to take up the role as “male head of the household.” He suppressed his own emotional needs and began to write letters to his mother full of the advice and emotional support he felt his father would have given.

The untimely death made James feel that he too would die young, and this early trauma, together with the pressure he felt to succeed at school led to a fissure in his personality that would widen with age. Kennaway’s biographer, Trevor Royle described this gradual change of character as:

James was the sophisticate, Jim the “nasty wee Scot”. Later, he came to characterize the split as James the domesticated man constrained by society and Jim the artist who should be allowed any amount of license.

Or, as Kennaway later described it:

James et Jim, man and artist, wild boy and introvert.

At school “James” was the likable, eager-to-please pupil; while “Jim” was beginning his first thoughts towards a career as a writer—as Kennaway explained in a letter to his mother:

...I feel I have been granted with more than one talent; in such a life my talent of sympathy would shine but my other talents would lie buried. On my part I would get lazier and fatter every day. I might however do this at the same time as I write and really go in for writing, but I must learn more about the English language before I can write any stuff worth reading.

After school, Kennaway carried out his National Service in the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders before going up to Oxford to study Modern Greats (Politics, Philosophy and Economics or P.P.E.). It was here he met Susan Edmonds, whom he married in 1951.

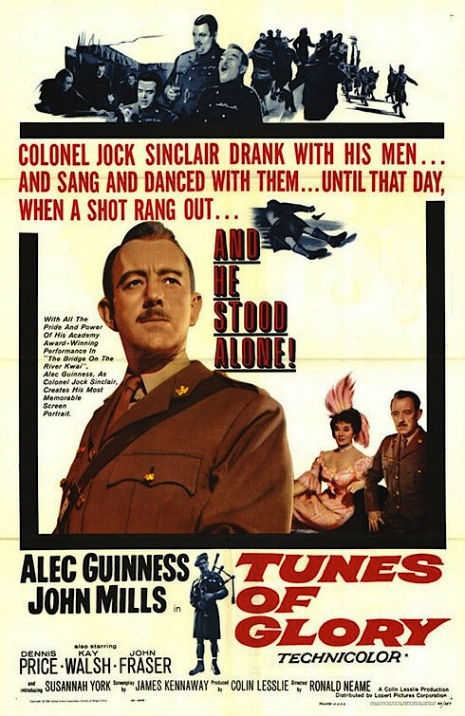

After university, Kennaway worked for a publishing firm, and in his spare time, started work on his first novel Tunes of Glory.

Published in 1956, Tunes of Glory was the story of a psychological battle between bully Major Jock Sinclair and war-wounded Lieutenant Colonel Basil Barrow for control of over a peacetime battalion stationed in a Scottish army barracks. The story had been inspired by many of the people and events Kennaway encountered during his National Service.

Max Frisch noted in his novel Montauk that a writer only ever betrays himself; this is true for Kennaway who channeled the experiences of his life through the prism of his writing.

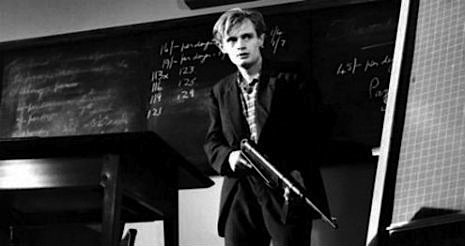

The book’s overwhelming success brought Kennaway more work as a writer: a commission to write an original screenplay. This became Violent Playground, which was filmed in 1957 with Stanley Baker, David McCallum, Anne Heywood and Peter Cushing. Its story of a juvenile delinquent holding a classroom of children to ransom was inspired by real siege in Terrazanno, Italy, when two brothers, armed with guns and dynamite, held ninety-nine pupils and three teachers to ransom. The brothers threatened to kill their hostages unless various demands were met. The siege ended after a teacher attacked and disarmed the brothers allowing the police to rescue the children. Kennaway followed the story in the papers, keeping numerous press clippings, and using the story for a key scene in his screenplay.

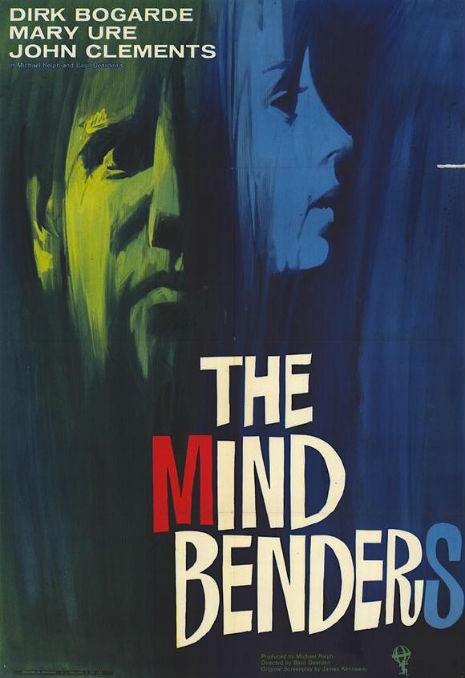

The following year, Kennaway was commissioned to write another film, this time he relied on the stories he had heard from academics at Oxford in the early 1950s.

The term “brainwashing” was first used by journalist (and CIA stooge) Edward Hunter in an article he wrote for the Miami News, 7th October 1950. Hunter used the term to bogusly describe why certain U.S. soldiers had allegedly co-operated with their captors during the Korean War. Simply put, Hunter was suggesting the Chinese had used various psychological techniques to create a false sense of friendship with which they could undermine, reprogram and brainwash American soldiers. This led to Western governments commencing their own brainwashing experiments.

In June 1951, a secret meeting at the Ritz Carlton Hotel in Montreal saw the launch of a CIA-funded, joint American-British-Canadian venture to fund studies “into the psychological factors causing the human mind to accept certain political beliefs aimed at determining means for combating communism and democracy” and “research into the means whereby an individual may be brought temporarily or perhaps permanently under the control of another.”

Dr. Donald Hebb of McGill University received a grant of $10,000 to examine the effects of sensory deprivation. Volunteers were paid to lie on a bed, cradled in a foam pillow (to block out external sounds), their arms wrapped in cardboard tubes (to limit movement and sensation), whilst wearing white opaque goggles. Without any external stimuli and only short breaks for testing, feeding and use of the toilet, the volunteers quickly began to hallucinate—seeing dots, colored lights, and faces. The experiments had disturbing affects on the volunteers with only a few managing to continue beyond two or three days—no one lasted the week.

The experiments progressed with the use of flotation tanks that became central to Kennaway’s screenplay.

In an article “The Pathology of Boredom” published in Scientific American, one of Hebb’s associates wrote:

Most of the subjects had planned to think about their work: some intended to review their studies, some to plan term papers, and one thought he would organize a lecture he had to deliver. Nearly all of them reported that the most striking thing about the experience was that they were unable to think clearly about anything for any length of time and that their thought processes seemed to be affected in other ways.

It was also noted during these experiments that the volunteers were overly susceptible to external sensory stimulation—making them open to ideas or beliefs they may have once opposed. In A Question of Torture, professor Alfred McCoy of Madison University, noted that during Hebb’s experiments “the subject’s very identity had begun to disintegrate.”

More on James Kennaway’s ‘The Mind Benders’, after the jump…