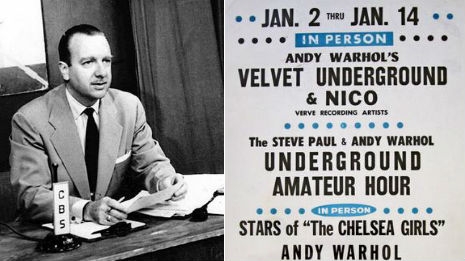

On the last day of 1965, viewers tuning into CBS were treated to a 6-minute report presented by Walter Cronkite himself called “The Making of an Underground Film”; DM’s Richard Metzger wrote about it last year. CBS’ news story prominently mentioned and showed a new band named the Velvet Underground—their first time on TV, ever.

The actual focus of the story was the underground movie scene, in particular an experimental filmmaker named Piero Heliczer. When CBS came a-callin’ to do its story, Heliczer was shooting a 12-minute short called Dirt, featuring the Velvet Underground, and that was the scene Heliczer happened to be shooting that day. (For some reason none of the fellows in the band are wearing a shirt.) Heliczer was actually an important figure in the development in VU’s sound, as we shall see below.

Reporter Peter Beard begins his report standing outside the Bridge, a theater located on 4 St. Marks Place in the East Village, an early center for alternative arts. In fact you can plainly see the word “FUGS” next to Beard on the facade of the Bridge. Remarkably, Cronkite interviews “the godfather of American avant-garde cinema,” Jonas Mekas and the undisputed king of über-experimental abstract movies, Stan Brakhage. CBS even shows more than 30 seconds of a Brakhage movie, presumably part of Two: Creeley/McClure, which is predictably a rapid-fire montage of stutter-y and blurry images—it almost feels like CBS’ little joke on the underground scene. Naturally, CBS also looks at Warhol’s Sleep and documents Warhol filming one of his own parties, at which Edie Sedgwick is joyousy bopping away.

One impetus for the CBS story was an interest in this new phenomenon, “underground” art. In Victor Bockris’ Up-Tight: The Velvet Underground Story, Sterling Morrison explains:

Whenever I hear the word “underground,” I am reminded of when the word first acquired a specific meaning for me and for many others in NYC in the early Sixties. It referred to underground cinema and the people and lifestyle that created and supported this art form. And the person who first introduced me to this scene was Piero Heliczer, a bona fide “underground film-maker”—the first one I had ever met.

On an early spring day John [Cale] and I were strolling through the Eastside slums and ran into Angus [MacLise] on the corner of Essex and Delancey. Angus said, “Let’s go over to Piero’s,” and we agreed.

It seems that Piero and Angus were organizing a “ritual happening” at the time—a mixed-media stage presentation to appear in the old Cinematheque. … It was to be entitled “Launching the Dream Weapon,” and it got launched tumultuously. In the center of the stage there was a movie screen, and between the screen and the audience a number of veils were spread out in different places. These veils were lit variously by lights and slide projectors, as Piero’s films shone through them onto the screen. Dancers swirled around, and poetry and song occasionally rose up, while from behind the screen a strange music was being generated by Lou, John, Angus, and me.

For me the path ahead became suddenly clear—I could work on music that was different from ordinary rock & roll since Piero had given us a context to perform it in. In the summer of 1965 we were the anonymous musicians who played at some screenings of “underground films,” and at other theatrical events, the first of which was for Piero’s films (I think that Barbara Rubin showed “Christmas on Earth” and Kenneth Anger showed a film also).

-snip-

Around this time, somehow, CBS News decided that Walter Cronkite should have a feature on an “underground” film being made. By whatever selection process, Piero was able to be the “underground film-maker”; since he had already decided to film us playing anyway, we got into the act (and besides, we had “underground” in our name, didn’t we? Maybe someone at CBS reads Pirandello).