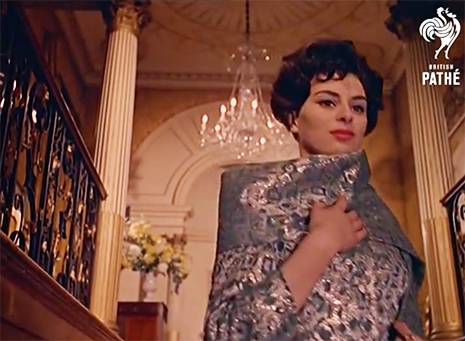

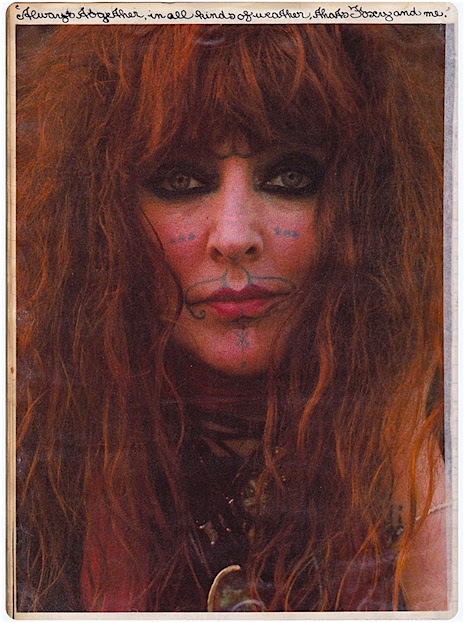

Vali Myers was never going to be ordinary. Her talent, wayward spirit and shock of flame-red hair marked her out for a life less ordinary. Ordinary was nice and nice was boring and Vali Myers hated boring.

But Vali had come from ordinary. She was born in Canterbury, Sydney, in 1930 to a wireless operator father and a talented violinist mother. Her mother had given up her career with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra to raise her family. Vali watched in growing horror as her mother slowly fell to pieces with the frustration of her small town life. Wives were expected to be drudges for the benefit of their husbands and nothing more. Her mother’s unraveling inspired Vali to focus on and nurture her own talents. She was good at art and loved to dance. She hated school and had difficulties with reading and writing. Her classmates thought her odd, but Vali thought them odd and frighteningly unimaginative.

She quit home at fourteen and worked in a factory to finance her ambitions to become a dancer. Vali eventually became a principal dancer with the Melbourne Modern Ballet Company. This early success confirmed her belief there was more to life than just being some man’s wife as most women her age were expected to be. She later told photographer Eva Collins:

Men always have women backing them up. But show me the bloke who back up his woman if she is an artist. They don’t like doing that, makes them feel like they’re sitting in the back seat. If a man is a real man, why does he need a woman to clean for him? He should look after himself, otherwise, he should go back to his Mummy!

At nineteen, Vali traveled to Paris where she earned a meager living dancing in cafes. For three years she lived on the streets in a hand-to-mouth existence with many of the city’s homeless youngsters. But she was free to do as she pleased and had the opportunity to mix with many of the city’s famous artists and writers like Jean-Paul Sartre, Jean Genet, Django Reinhart, and Jean Cocteau, with whom she often smoked opium.

This gaggle of young beatniks on the fringes of Paris attracted the interest of Dutch photographer Ed van der Elsken, who chose the iconic Vali as the main character in photo-essay Love on the Left Bank (1954). Van der Elsken’s black & white photographs followed Vali as young beatnik girl “Ann” through the gangs of bohemians, musicians, and vagabonds who hung around the bars, clubs, and flophouses of St Germain-des-Prés. Vali’s distinctive look inspired a whole generation of women including Patti Smith who later described Vali as:

...the supreme beatnik chick—thick red hair and big black eyes, black boatneck sweaters and trench coats.

Though a freeform impressionistic tale, van der Elsken’s book did capture much of the life Vali was living among the “young men and girls who haunt the Left bank”:

They dine on half a loaf, smoke hashish, sleep in parked cars or on benches under the plane trees, sometimes borrowing a hotel room from a luckier friend to shelter their love. Some of them write, or paint, or dance.

Vali was dancing and painting and keeping a journal of her daily life. She was occasionally arrested as a vagabond but was usually bailed out by Jean Cocteau. During this time, she met and married Hungarian architect Rudi Rappold and for a time they lived in Vienna, Austria, and then in Positano, Italy. After Rappold’s death, Vali remained in Italy where she had gained the moniker “the Witch of Positano” because of her outsider existence. She continued to paint and write and spend time looking after the local wildlife.

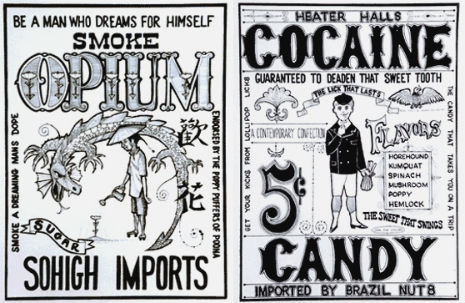

In the sixties, Vali moved to London and then to New York. She was a friend and muse to Salvador Dali and became friends with the likes of Mick Jagger and Marianne Faithful. In 1968, Vali starred with Marianne in a little-seen film called Dope about London’s drug scene. Vali then moved to New York where she lived at the Chelsea Hotel. It was here she met Patti Smith for whom she famously tattooed a lightening fork on her knee. But Vali didn’t like New York. It was brutal, hard and false. After an aneurysm in 1994, Vali eventually returned to Australia.

With her gypsy dress, her flaming red hair and distinctive facial Maori tattoos, Vali was instantly recognizable wherever she went. But it was her outsider artwork that achieved the greater attention. Her paintings were bought by museums and galleries in America, Europe, and Australia and were collected the likes of Mick Jagger and George Plimpton.

Vali died from cancer in February 2003. She had no regrets. She had lived her life as she wanted to live it. On her deathbed she said:

I’ve had 72 absolutely flaming years. It doesn’t bother me at all, because, you know, love, when you’ve lived like I have, you’ve done it all. I put all my effort into living; any dope can drop dead. I’m in the hospital now, and I guess I’ll kick the bucket here. Every beetle does it, every bird, everybody. You come into the world and then you go.

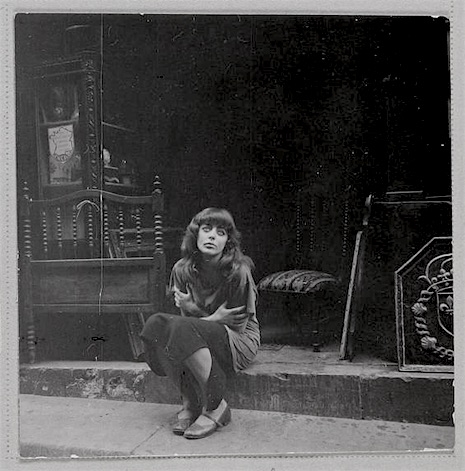

Vali in Paris photograph by Ed van der Elsken.

See some of Vali’s artwork and more iconic photos, after the jump…