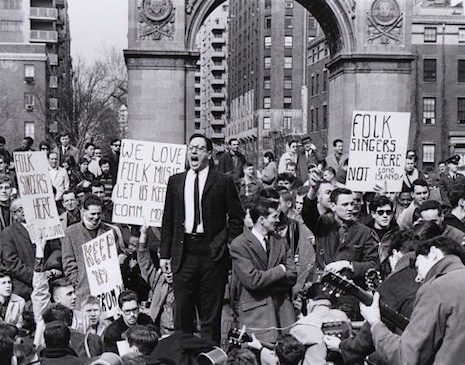

The protestors were peaceful. They didn’t look like revolutionaries. They were dressed in suits and ties. They were singing “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

But the cops still attacked them with billy clubs.

In the spring of 1961, Israel (“Izzy”) Young taped a sign to the window of his shop in Greenwich Village, New York. The handwritten sign announced a protest rally at the fountain in Washington Square Park at 2pm on Sunday April 9th .

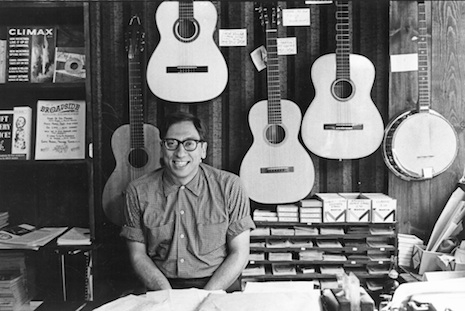

Izzy was the proprietor of the Folklore Center at 110 MacDougal Street, a shop that sold books, records and everything else relating to folk music. Since it opened in 1957, the Folklore Center had been the focal point for young folk singers, beatniks and assorted musicians to gather together, hang out, talk, play and listen to music.

After the Second World War, Greenwich Village was the gathering point for all the disaffected youth who wanted to escape the conformity and boredom of suburbia. They were brought by the district’s association with the Beats and jazz musicians who had lived and played there during the 1940s and early 1950s. Often their first point of call was Izzy’s shop. Among the many youngsters who visited there was a young Bob Dylan. Izzy arranged Dylan’s first concert at Carnegie Hall. He “broke [his] ass to get people to come.” Tickets were two bucks apiece. Only 52 people turned up—though later hundreds would tell Izzy they were there.

Izzy Young in the Folklore Center circa 1960.

Since the late 1940s, folk musicians had gathered at the fountain in Washington Square Park. They brought their guitars and autoharps to play and sing songs. It was peaceable enough but some residents thought the Sunday gatherings brought “undesirables” to the neighborhood—by undesirables they meant African-Americans.

In April 1961, the new Commissioner of Parks Newbold Morris decided to take action. He banned singing in Washington Square Park. As Ted White later reported the events of that fateful day in the park in Rogue magazine, August 1961:

For seventeen years folksingers had been congregating on warm Sunday afternoons at the fountain in the center of the small park, unslinging their guitars and banjos and quietly singing songs. There would be a varied number of groups—perhaps ten or more—rimming the fountain, each singing a particular variety of folk music, from Negro work songs and blues to Kentucky hillbilly bluegrass, with perhaps an Elizabethan ballad from the West Virginia hills thrown in occasionally. As the years passed, the city government began showing an increasing hostility to the use of public facilities by the public, and for the last fourteen years, permits have been required before “public performances” could be given in any park. What this means is that a group of kids singing to each other on a weekday evening would be forcibly silenced by the ever-patrolling police for failing to possess a “permit,” or a young man playing a harmonica to himself quietly while sitting on a park bench might be suddenly ordered, “Move on, you!” and find himself run out of the park.

...

And now the new Parks Commissioner has refused a permit to the folksingers for their Sunday afternoon gatherings. Why? The same old story: “The folksingers have been bringing too many undesirable elements into the park.”

“Undesirable elements?” Yes, healthy young kids, racially mixed and unprejudiced enough not to care, concerned only with having the chance to assemble in the open sun and air and to be able to enjoy themselves harmlessly and happily. Sam Schwartz, a Brooklyn father, told me “Sure I let my kid—he’s a teenager—come and sing here. Why not? It’s a good, healthy activity. What’s wrong with folksongs?”

Ron Archer, a young jazz critic who lives in the West Village (an apparently less troubled area), said “Why shouldn’t people sing in the Square? If Morris is so concerned about the safety of the parks, why doesn’t he clean out the muggers and rapists in Central Park, where it isn’t safe to walk at night? Why doesn’t he go after the local punks who prowl the edges of this park at night? Why take after a group which is as harmless as the old men who play chess here, and who are just about as ’undesirable’?”

“You know what ’undesirable’ means, don’t you?” a name jazz musician told me. “It means ’Negro’. A few of the folksingers are Negroes.”

“I came up here from Mississippi,” says Bob Stewart, a Realist cartoonist who lives in the Village, “to get away from the prejudice, and now I get complaints from my landlord whenever I have a Negro friend up in my apartment.”

“The racial bias is definitely behind the whole thing,” Izzy summed it up. “It’s part of the big squeeze on the Italians.”

In response to the ban, Izzy applied for a permit to sing in the park. It was rejected. He therefore organized a protest rally.

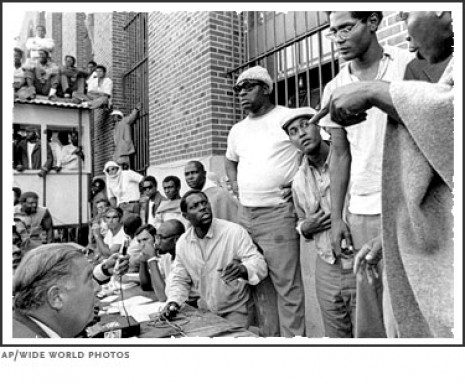

Izzy Young talks to a cop at the start of the demonstration.

On Sunday April 9th at 2pm, around 500 men and women—smartly dressed, some in suits and ties and carrying placards—peaceably approached the fountain at Washington Square Park. They were stopped by a cop. He wanted to know who was in charge. Izzy Young made his way to the front of the crowd and talked to the officer. He explained they were allowed to protest peaceably. It was within their constitutional rights to do so. The cop told Izzy they couldn’t sing, that singing was banned. They would be arrested if they broke the ban. Izzy countered by saying singing was a form of speech and they had a right to freedom of speech. He added:

It’s not up to Commissioner Morris to tell the people what kind of music is good or bad. He’s telling people folk music brings degenerates, but it’s not so.

The cops were not impressed. They began to move menacingly towards the demonstrators. Izzy thought if they started singing “The Star-Spangled Banner” the police would not hit them “on the head.” He was wrong. As the demonstrators sang the national anthem the cops started laying into them.

Ten demonstrators were arrested. Dozens were injured. The press hyped the story up as a ‘Beatnik riot’ where some 3000 people attacked the cops. This story was quickly dropped as it was widely known not to be true.

Keep reading after the jump…