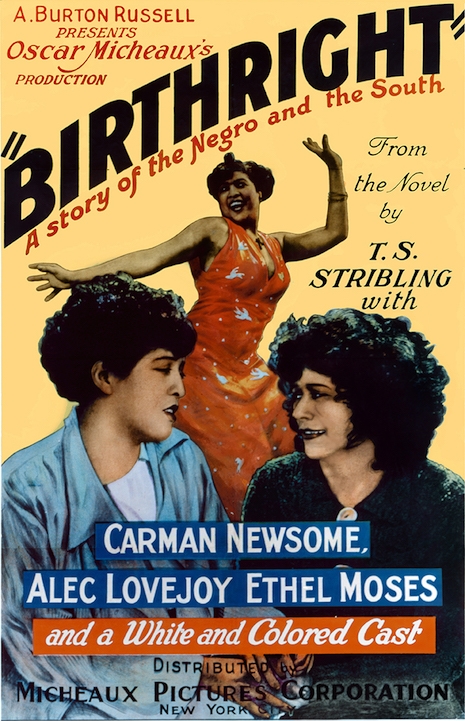

Birthright, 1939. A black Harvard graduate confronts racism.

The images on this page come from a remarkable book that came out late last year, Separate Cinema: The First 100 Years of Black Poster Art, by John Duke Kisch; it’s an incredibly wide-ranging look at the posters of “black cinema” writ large, a category that includes not just the “race films” shown here but also Birth of a Nation, earnest Hollywood dramas, The Jazz Singer, Blaxploitation flicks, South African movies addressing apartheid, breakdancing movies from the 1980s, and much more. The book’s credibility couldn’t be greater, insofar as Henry Louis Gates Jr. supplies the foreword and Spike Lee the afterword.

The posters depicted here tell a tale of true segregation, a “separate but equal” industry, so to speak, that served up gripping melodramas to its chosen audience just as surely as Warner Bros. did for white audiences. The undisputed master of this period is Oscar Micheaux, who directed a couple of these movies. By Kisch’s lights “the most successful early black independent film producer and director,” Micheaux was the son of a Kentucky slave before working as a railway porter and homesteader; around World War I he started directing and producing movies, of which he directed more than 40 before he was done. Kisch describes his basic formula as follows:

Micheaux’s features were usually far superior to those made by other independent black studios, largely because he took a familiar Hollywood genre and gave it a distinctive African-American slant. Committed to “racial uplift,” he cast black characters in non-stereotypical roles, as farmers, oil men, explorers, professors, Broadway producers, or Secret Service agents. … He brought to the screen diverse social issues that faced black America, and also portrayed an ideal world in which blacks were affluent, educated, and cultured. In the 1930s, his films represented a radical departure from Hollywood’s portrayal of African Americans as jesters and servants.

In our age, posters like this are simultaneously dazzling and upsetting, almost as taboo as the interracial drama The Exile (below) was in its day. Underlying so much of the rhetoric surrounding the racial situation in America is the understanding that all those bad things belonged to and are limited to the past; the horrors of Ferguson, Staten Island, Cleveland in 2014 showed everyone that no such assumptions are safe—even as Steve McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave (it’s included in the book too) both harks back to these unsettling movies and signals the potential for lasting change.

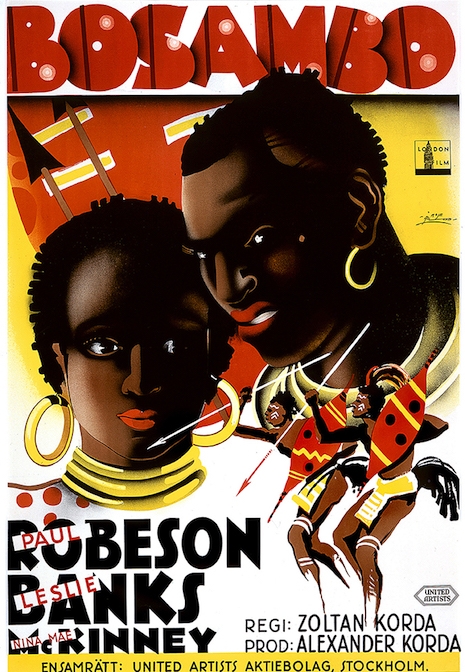

Bosambo, 1935. British District Officer in Nigeria in the 1930’s rules his area strictly but justly, and struggles with gun-runners and slavers with the aid of a loyal native chief.

Black Gold, 1928. A town abandons its previous ways of life for the glamour and drama of the oil drilling trade.

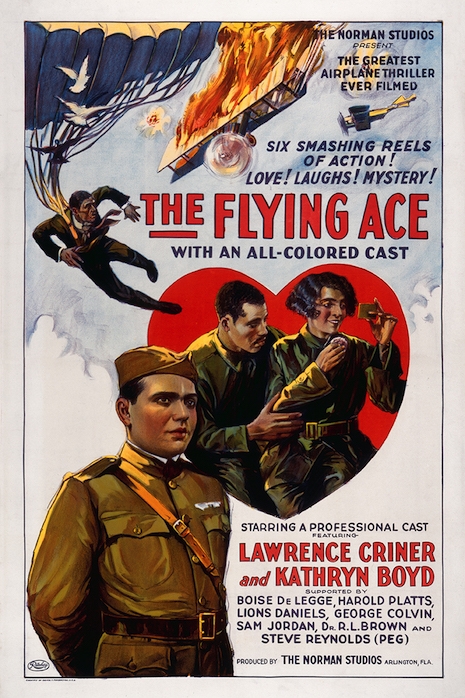

The Flying Ace, 1926. A veteran World War I fighter pilot returns home a war hero and immediately regains his former job as a railroad company detective.

More after the jump…