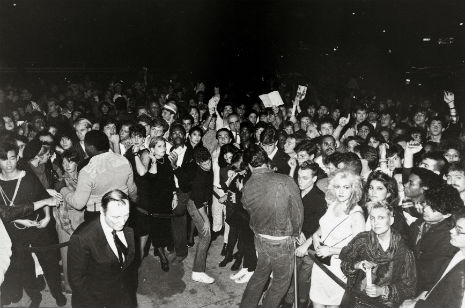

There was, for slightly better than a decade, a “golden era” of insanely decadent, yet terribly smart and sophisticated New York City nightlife. For sake of argument, let’s say it began with Studio 54 opening in 1977 and ended in the late 80s due to several factors, including AIDS, the invasion of the “club kids” and the general financial difficulties of operating anything requiring significant amounts of space in such an expensive city. Some (arguably most) of it happened before my time, but I did get to personally experience a lot of it. When I was younger, I went out just about every single night. I felt like if I stayed in, I might miss something. At the time, this was most certainly true and I made it a point to try to cram in as many crazy experiences as I could. Quite successfully, I might add…

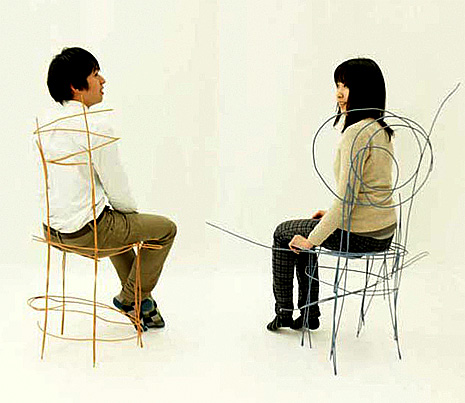

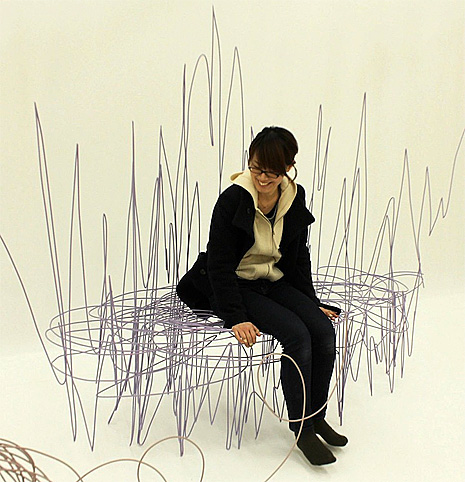

Although I can’t say that it was personally my favorite nightclub (the Danceteria was more what I was into, with hot girls my own age), I would have to say that AREA was probably the best or greatest New York club of the 80s, at least in my experience. Every six weeks, a team of about 30 artists and carpenters would work around the clock to ready the club for the opening of a new and quite elaborate artistic “theme” like “Red” or “Confinement” or “Suburbia.” To get across what a spectacularly mind-bending and magical place it was, here’s what I saw there, with my own eyes, coincidentally on my very, very first night as a “real” New Yorker:

was probably the best or greatest New York club of the 80s, at least in my experience. Every six weeks, a team of about 30 artists and carpenters would work around the clock to ready the club for the opening of a new and quite elaborate artistic “theme” like “Red” or “Confinement” or “Suburbia.” To get across what a spectacularly mind-bending and magical place it was, here’s what I saw there, with my own eyes, coincidentally on my very, very first night as a “real” New Yorker:

I arrived in New York City in late November of 1984. After setting myself up in a (surprisingly decent) $50 a night hotel, I scanned the Village Voice for something fun to do, before deciding to go to the Danceteria. Not quite understanding what was the appropriate time to show up at a Manhattan hot spot at that age (I had just turned 19 and was in fact too young to even be there legally) I arrived too early, before practically anyone else had shown up. I sat on a couch and watched Soft Cell videos as the bar staff set up for the evening. Soon I was joined by a couple about my age—a sharp-dressed black guy and his blonde Swedish girlfriend. We struck up a friendly conversation and he revealed to me that he had cocaine—about a kilo’s worth—and did I want any? The answer to that was a resounding “Yes!” and he used a NyQuil cup to scoop out at least an eight-ball from a big ZipLoc bag and just handed it to me.

So this is New York, huh? I think I like it already!

Soon we were joined by another pair of early birds, future “club kid murderer” Michael Alig—then a first year student at Fordham University in the Bronx—and a female friend. They, too, were offered some a lot of coke, accepted gladly, and Michael (who was later played by Macaulay Culkin in Party Monster ) asked if we were planning to attend the opening night of AREA

) asked if we were planning to attend the opening night of AREA ‘s “Faith” theme later?

‘s “Faith” theme later?

I’d just gotten to town and had never even heard of the place. He insisted that he had the pull to get us all in for free, and that it was going to be amazing, so around midnight, we hopped into a cab to 157 Hudson Street, just below Canal, and disembarked into a teeming throng of people waiting to get in, waving their arms at the doormen, Day of the Locust style. True to his word, the sea of people parted and Michael got us all in for free (we were dressed weird so that helped), but as I was between the taxi and the door, I could see that there was a procession coming down the street, carrying a man on a cross with arrows—in my mind they were flaming arrows—in his stomach, like St. Sebastian. It was attention grabbing, I can assure you.

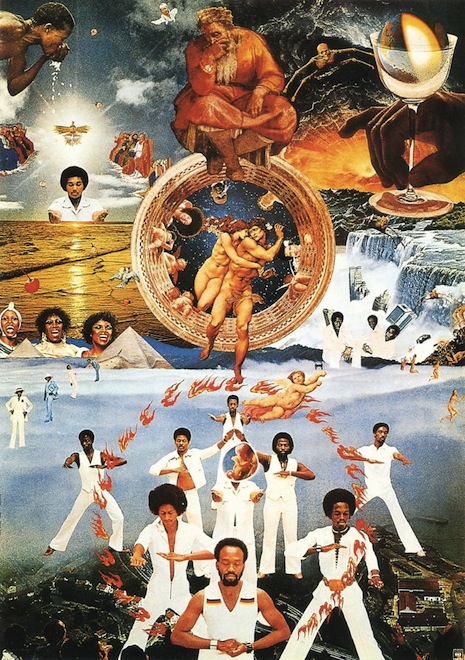

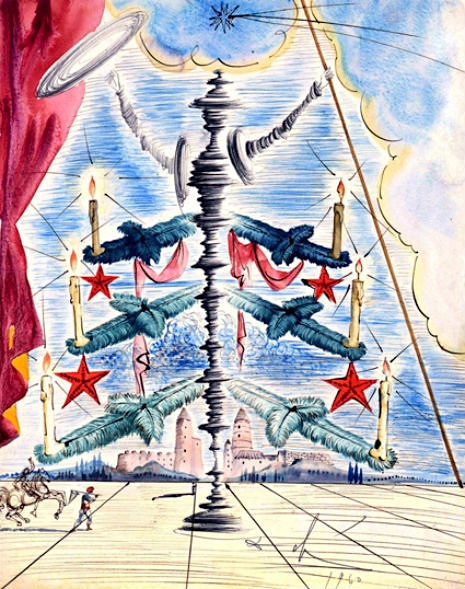

As you entered AREA , there was an impressive castle-like stone hallway, with windows on the right-hand side like you might see in a department store, but with works of art, displays, people, animals, performance art and all manner of things going on inside them. Soon the crucified guy was being carried down the hallway before he was ultimately deposited upright into a shark pool in the lounge. AREA

, there was an impressive castle-like stone hallway, with windows on the right-hand side like you might see in a department store, but with works of art, displays, people, animals, performance art and all manner of things going on inside them. Soon the crucified guy was being carried down the hallway before he was ultimately deposited upright into a shark pool in the lounge. AREA ‘s “Faith” theme saw the entire nightclub transformed into a gigantic gallery of campy religious iconography and spiritual irreverence (The bathrooms, notoriously unisex, I recall having video monitors with the Pope, Jim Jones and Jerry Falwell over the urinals at eye-level).

‘s “Faith” theme saw the entire nightclub transformed into a gigantic gallery of campy religious iconography and spiritual irreverence (The bathrooms, notoriously unisex, I recall having video monitors with the Pope, Jim Jones and Jerry Falwell over the urinals at eye-level).

Utterly astonishing to me, Andy Warhol was there. Michael asked “Oh, do you want to meet Andy?” I said “Sure!” and he promptly pushed me at the great artist, from behind, as HARD as he could, with both arms. So hard that I nearly knocked Andy Warhol on his ass. (Luckily for me, Warhol had seen what had happened and directed his annoyance at Michael and not at me, so I was able to slink away, mortified, and move to another part of the club.)

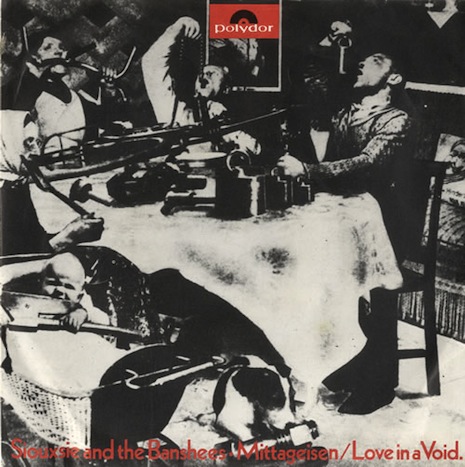

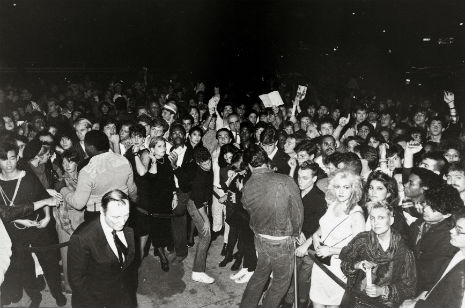

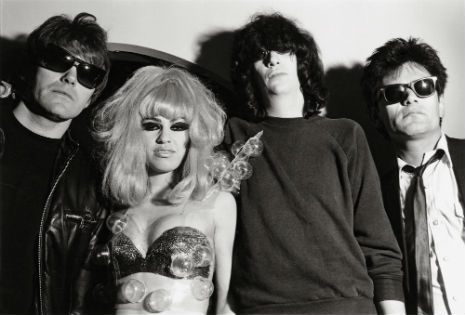

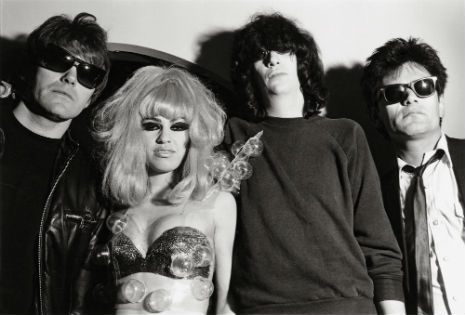

The crowd AREA attracted was eclectic, to say the least. You had the freaks, the beautiful people, the up-and-comers, the semi-famous, the very famous, the very wealthy, fashionistas, artists, gallerists, professional liggers and hanger-oners, art students, rich Europeans, frat boy Wall Street-types (the ones who actually paid to get in and for their drinks) and just about any type of human being you can imagine, really. It was the sort of place where you could look around the room and see Joan Rivers, the B-52s, Boy George, Allen Ginsberg, Billy Idol, members of the Psychedelic Furs or Duran Duran, John Waters, John Sex, Ann Magnuson, Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat, David Byrne, Malcolm McClaren, Lauren Hutton, Matt Dillon, Federico Fellini, Barbara Walters, Peter Beard, Michael Anderson (the dwarf from Twin Peaks), Nile Rodgers, Stephen Sprouse, Steven Meisel, transsexual model Teri Toye, Calvin Klein, Sting, etc, etc, etc, all potentially on the very same night. Their opening parties, especially, were not to be missed under any circumstances. Everyone in attendance knew there was no cooler place to be that night anywhere else in all of Manhattan, if not the entire planet.

attracted was eclectic, to say the least. You had the freaks, the beautiful people, the up-and-comers, the semi-famous, the very famous, the very wealthy, fashionistas, artists, gallerists, professional liggers and hanger-oners, art students, rich Europeans, frat boy Wall Street-types (the ones who actually paid to get in and for their drinks) and just about any type of human being you can imagine, really. It was the sort of place where you could look around the room and see Joan Rivers, the B-52s, Boy George, Allen Ginsberg, Billy Idol, members of the Psychedelic Furs or Duran Duran, John Waters, John Sex, Ann Magnuson, Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat, David Byrne, Malcolm McClaren, Lauren Hutton, Matt Dillon, Federico Fellini, Barbara Walters, Peter Beard, Michael Anderson (the dwarf from Twin Peaks), Nile Rodgers, Stephen Sprouse, Steven Meisel, transsexual model Teri Toye, Calvin Klein, Sting, etc, etc, etc, all potentially on the very same night. Their opening parties, especially, were not to be missed under any circumstances. Everyone in attendance knew there was no cooler place to be that night anywhere else in all of Manhattan, if not the entire planet.

It was an extraordinary nightclub for an extraordinary time in New York’s history. The city was a wild, creative and dangerous (define that how you will) place then. AREA was a reflection of the best of what the city had to offer, a place where uptown wealth met downtown chic. It’s one of the longest-running, most brilliantly realized art projects—one pulled off by a small army of weirdos (many of AREA

was a reflection of the best of what the city had to offer, a place where uptown wealth met downtown chic. It’s one of the longest-running, most brilliantly realized art projects—one pulled off by a small army of weirdos (many of AREA ‘s hardworking artists were junkies), visionaries and money men—probably, I don’t know… ever. That they were able to sustain it for so long, night after night, theme after theme at such a high level creatively and then go out while they were on top makes it seem all the more remarkable.

‘s hardworking artists were junkies), visionaries and money men—probably, I don’t know… ever. That they were able to sustain it for so long, night after night, theme after theme at such a high level creatively and then go out while they were on top makes it seem all the more remarkable.

But as an art form, a party, no matter how legendary it becomes in the minds of the people who were there, is still a very ephemeral thing. Aside from memories, there are only photographs, videos and mementos left (AREA was well-known for their elaborate invitations. How I wish I’d have kept mine!). The multi-leveled social/artistic/business genius that was AREA has now been commemorated in what I’d rank as perhaps the very best art/art history book of the year. If you were there, Abrams’s AREA: 1983-1987

has now been commemorated in what I’d rank as perhaps the very best art/art history book of the year. If you were there, Abrams’s AREA: 1983-1987 is a must and chances are that you already own it. If you weren’t there, it’s fascinating record of an amazing, once in a lifetime scene that will hopefully inspire some new crew to take on something this elaborate again one day. It’s a book with a cult audience, to be sure, but a cult audience that will absolutely treasure it.

is a must and chances are that you already own it. If you weren’t there, it’s fascinating record of an amazing, once in a lifetime scene that will hopefully inspire some new crew to take on something this elaborate again one day. It’s a book with a cult audience, to be sure, but a cult audience that will absolutely treasure it.

Put together by AREA ‘s Eric and Jennifer Goode, with an introduction by Glenn O’Brien, principal text by Stephen Saban (beyond a doubt the very best person for the job) and the photography of Volker Hinz, Ben Buchanan, Patrick McMullan, Wolfgang Wesener, Michael Halsband, Dana Buckley and others. On every level, I’d rate this publication a perfect 100/100, as a book (in literary, historical sense) and as a beautifully designed object.

‘s Eric and Jennifer Goode, with an introduction by Glenn O’Brien, principal text by Stephen Saban (beyond a doubt the very best person for the job) and the photography of Volker Hinz, Ben Buchanan, Patrick McMullan, Wolfgang Wesener, Michael Halsband, Dana Buckley and others. On every level, I’d rate this publication a perfect 100/100, as a book (in literary, historical sense) and as a beautifully designed object.

More photos of AREA here.

Below, this John Sex video, “Hustle With My Muscle,” directed by the late Tom Rubnitz, is one of the few examples I can find of inside AREA on YouTube. The theme at this time would have been “American Highway” in 1986. Sadly, you really can’t get a sense of the size of the club from what you see here.

on YouTube. The theme at this time would have been “American Highway” in 1986. Sadly, you really can’t get a sense of the size of the club from what you see here.