On May 29, CAN founder Irmin Schmidt will mark his 83rd birthday with the release of Nocturne, a live recording of his piano performance at last year’s Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival. A lightly edited transcript of our two recent conversations by phone, quarantine-hushed Los Angeles to nightingale-loud Roussillon, follows.

How is quarantine in Provence?

I’m in the countryside, and everything is calm and beautiful.

What do you remember about the performance in Huddersfield that this record comes from?

Since it was the first concert I did—real concert, I did single performances on prepared piano, small things, but it was the first real concert with the prepared piano, with my new thing—I was quite excited about it, and didn’t know what will happen.

What impressed me was, during the performance, I thought the public had disappeared! It was so silent, I thought maybe they [chuckles]... it sounded as if I’m all alone. They liked it! They listened so concentrated. It went very well.

I actually wondered—on the recording there’s so little audience noise, I wondered if it had been taken out. But no, they were really listening.

They were really extremely silent. There was one very, very little cough, once, in the whole thing. And then the guy afterwards came to me and said, “Excuse me, I had to cough once.” I couldn’t believe it! They were—I mean, as if they weren’t there.

But it was pure concentration there! There were lots of people afterward coming to me and said they were really sort of hypnotized, they really listened. And that was a great compliment, because I didn’t know how would it be. It was a new thing performing this. Although I have, in the Sixties, I made a lot of piano recitals with contemporary music: Messiaen, and Webern, and Stockhausen Klavierstücke, and Cage, a lot of Cage. But this is long ago; in between there were some different things, and that was the first time I was all alone again, facing a public with my piano, and it was wonderful.

It’s sad; I have so many offers now to play all over—in Norway, in Warsaw, in Prague, in Germany and in France—and I can’t do it.

Because of the virus.

Because of the virus, yeah. I don’t worry about it so much because I’m so much better off where I am, in this beautiful countryside. I’m much better off than so many other people in towns. So I don’t… lamentate.

If you have to be stuck somewhere, I would think Provence is not a bad place.

Exactly, [laughs] especially where I am, I mean, I have a big piece of land [signal breaks up] I can be alone and it’s beautiful, it’s calm. No reason to complain.

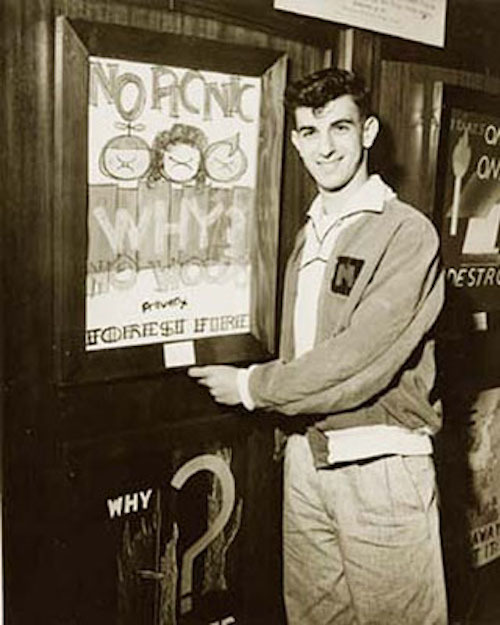

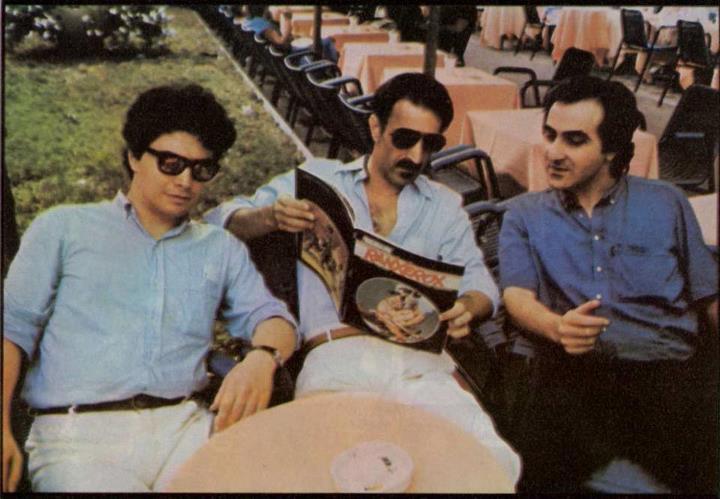

Photo by Lucia Margarita Bauer

Have you noticed any changes in the environment?

Not really, because I’m living really in the countryside. I mean, it’s springtime, it’s wonderful. There is no change visible because there has never been any traffic in that part of the world.

I mean, the only thing I realize is there are less planes going above our area. But I don’t know, if that affected something, it’s not visible. Actually I can’t say I noticed anything in the environment, because I am not in the town. In towns, everybody tells me it’s totally different; there are more birds and animals. But where I am in the countryside, it’s like always.

But there is one strange thing. You know, our house is called Les Rossignols, our address, and that means “the nightingales,” because there have always been nightingales. There is some water, there is a pond and there is a creek down there, and there have always been some nightingales. This year, it’s double as much, which is the only remarkable thing. There are more nightingales this spring, singing, which is wonderful. I don’t know why. It cannot be because it’s more clean where I am, but maybe it was easier for them to come, I don’t know. But that’s actually the only change, and that can be just a a coincidence. That must not necessarily be due to the lockdown.

Can you tell me about the piano pieces in some more detail? I’m curious first of all what the equipment is. I know on the studio album you have two different pianos, one prepared and one unprepared.

Right. Yeah.

Which I think has been your practice for a while, right?

Yeah, I have two grands in my house. For the studio record, I prepared one and left the other one unprepared, just untouched. On some pieces, I only played the prepared—which, when I say “prepared,” never is the whole piano prepared. It’s never all strings prepared. It’s sort of half of the piano. Because I love this kind of… these vibrations, these sounds of the real piano sound with the prepared, which has harmonics, which create a strange kind of tension between the not-prepared and well-tuned strings, and these prepared ones which have very complex harmonics. I love that.

Yeah, on the studio record, I played two pianos. In performance, in a concert, I can do only one piano, so it’s half-prepared. And you hear it on the Huddersfield recording, there is this mixture between the sounds of the real piano and the prepared piano, and that’s what I love so much about it, because it makes this kind of tension in the harmonics, and these vibrations which are created by the difference of tuned and prepared [strings].

When I made the studio recording, I started with a prepared piano, and the first piece of the studio record is totally improvised. One go. I mean, the time it is on the record, that’s the time I played, and there’s nothing edited and nothing changed and manipulated. That’s how it started.

And then I made some field recordings. I have a little pond, and around the pond there is bamboo and reeds. So I went through them, and sometimes sort of moved them rhythmically, sometimes just went through this, and we recorded that, and I played to that.

Continues after the jump…

\

\