Anders Petersen was eighteen when he traveled from his home in Sweden to Hamburg’s red light district the Reeperbahn. He wanted to escape his upbringing, shed his comfortable bourgeois skin and try on another to see how it felt. His parents had separated when he was young and he had been brought up by his grandmother in the quiet of the countryside amid fields and cherry trees and a darkening border of a forest. It was an idyllic fairytale world, but boring.

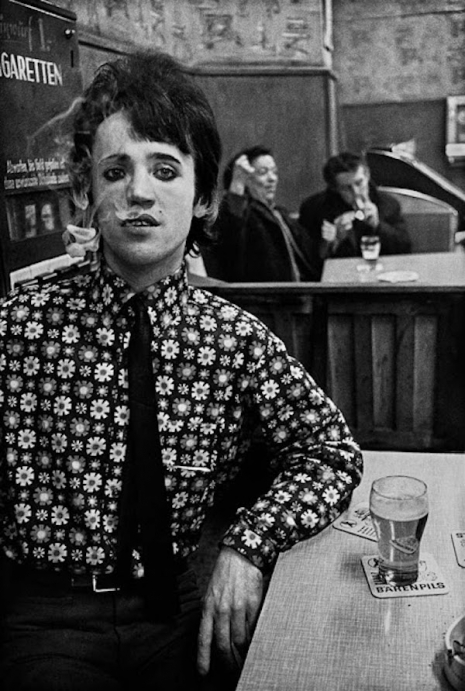

The Reeperbahn was a chaotic world of excitement, and pleasure, and excess, and danger. He met a green-eyed Finnish woman who worked the main drag. They became lovers and Petersen was introduced to the world of prostitutes, drag queens, drug addicts, drunks, pimps, and thieves. He took courage from his lover, from beer and from amphetamines (Preludin) to finally break free of the rules and manners, the lies and constraints of his bourgeois childhood. He had found himself another family who lived their lives without care, without shame, without judgment or censure. Petersen made friends with these characters who shambled joyously through the night at the local bar like the Café Lehmitz. All too soon it was over. His Finnish girlfriend broke-up their relationship and told Petersen to go home before his life was lost in the bars and lights, in the dirt and the chaos.

Dismayed, Petersen reluctantly returned home. But he knew his life had changed and he needed to find a way to express himself. He considered painting, but this, he found, was too lonely a thing. He was a social animal and wanted to be involved with the lives of others. This led him to photography—something he had been quietly considering for some time. He started studying under the great Swedish photographer Christer Stromholm who told him to find the things that were important to him. Be humble, be personal, work hard, and never be satisfied. It was sound advice.

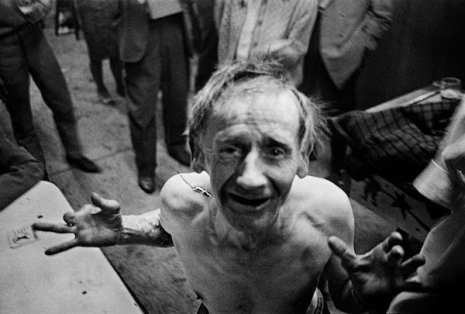

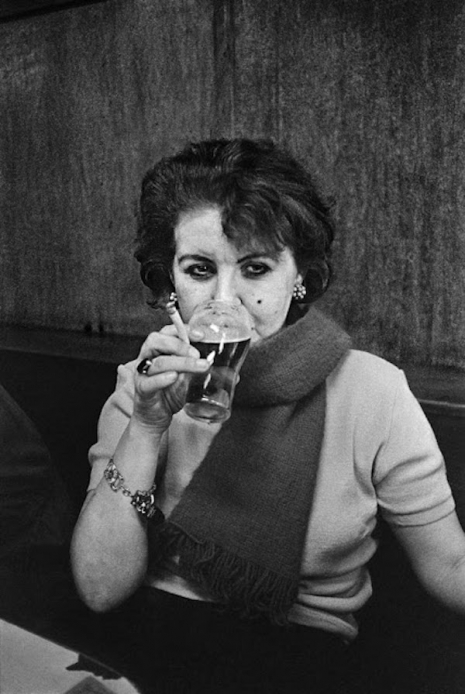

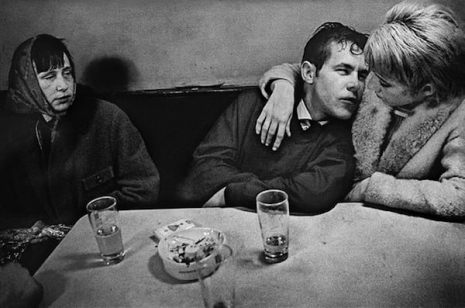

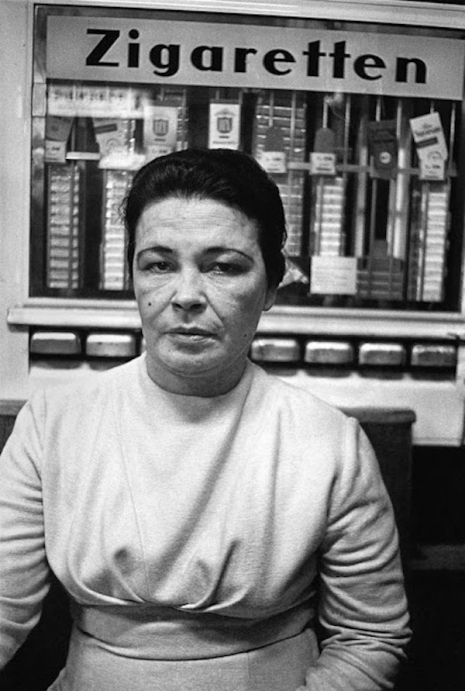

In 1967, Petersen returned to the Reeperbahn and the Café Lehmitz. He discovered some of the friends he had made had died. Now he knew he must document this new family. He sought an in through a friend. One night he arrived at the Café Lehmitz with his camera in hand. He placed it on a table and became so involved with the drinking and talking, the dancing and singing, that he did not notice his camera had been picked up and was being thrown about among the customers like a toy. Some were taking pictures of themselves. Some wanted Petersen to take their picture. Petersen started photographing the people who hung around the bar in a scrum; the couples who argued or flirted with each other over the cheap Formica tabletops; the prostitutes who smiled and wanted you to buy them a drink; the old drunk men who wanted to fight and staggered shirtless shouting at the customers.

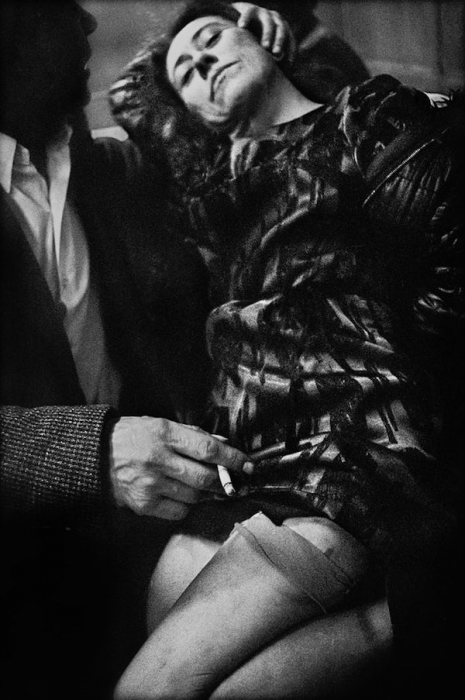

Petersen shot with his heart, with his guts, with his instinct. He did it without thinking. It was almost reflexive. Then when the pictures were printed on a contact sheet, he figured out which photograph worked best, which picture asked more questions than it answered, which image best captured an atmosphere, a character, a life, or a feeling. He shot more than he needed. He now has a house and studio crammed with too many photographs.

Over the next three years, Petersen traveled back-and-forth between Sweden and the Café Lehmitz documenting the harsh, brutal, yet tightly knit lives of the people who lived and worked on the Reeperbahn’s cobbled streets. His first exhibition was held at the bar itself with his pictures nailed crudely to the wall and the customers eventually removing their portraits one-by-one until only Petersen’s self-portrait remained.

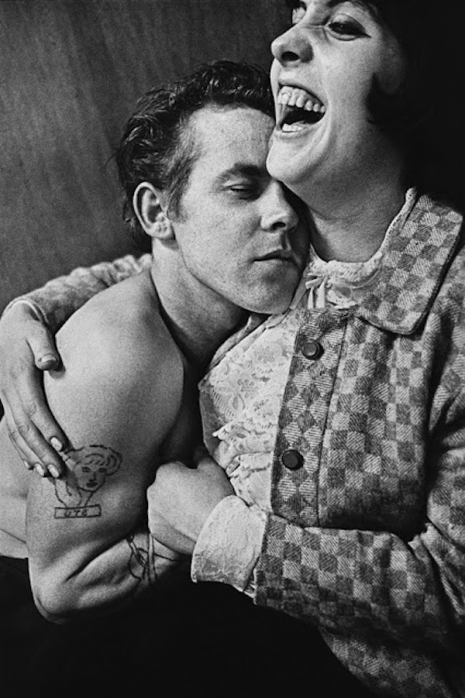

He published his photobook of the Café Lehmitz in 1978. It established Petersen as one of the greatest living documentary photographers. His style was intimate, unswerving, uncritical, and direct. One of the book’s most famous images—a young tattooed man named “Rose” embraced by a laughing older woman called Lily—was featured on the cover of Tom Waits’ album Rain Dogs. The image definitively captured the image Waits was selling of a Beat poet and outsider artist.

In our slowly homogenized world, where nobody smokes and nobody drinks, where all the streets are the same and the shops are the same, and everyone is safe and free to be a consumer, Petersen’s photographs of the Café Lehmitz captured a now seemingly distant world where people shared harsh brutal lives filled with excitement and danger, derangement and excess, love and happiness, always under the always-present shadow of death.

Via Vintage Everyday and the Guardian.