Andy Kershaw is a writer, a multi-award-winning broadcaster (he once shared an office with John Peel for 12 years, and has won more Sony Radio Awards than any other broadcaster, and was one of the presenters on Live Aid). He is also a foreign correspondent, who eye-witnessed and reported on the Rwandan genocide. His fearlessness as a reporter saw him banned from Malawi under the dictatorship of Dr Hastings Banda.

But that’s only part of this Lancastrian’s incredible story.

Kershaw has worked for Bruce Springsteen; was Billy Bragg’s driver, roadie and tour manager; went on a blind date with a then unknown Courtney Love (to see Motorhead); was propositioned by both Little Richard and Frankie Howerd; spent a week riding out with Sonny Barger and the Oakland Hell’s Angels; went with Red Adair and Boots Hansen to the burning oil well-heads in Kuwait in 1991; and was immortalised by Nick Hornby in High Fidelity, which was later filmed with John Cusack.

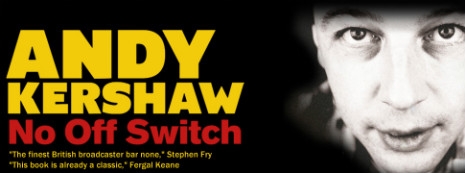

This has made Andy Kershaw a bit of a legendary figure—a kind of distant British relative to Hunter S Thompson. This and much more can be found in Kershaw’s excellent autobiography No Off Switch, which I can thoroughly recommend.

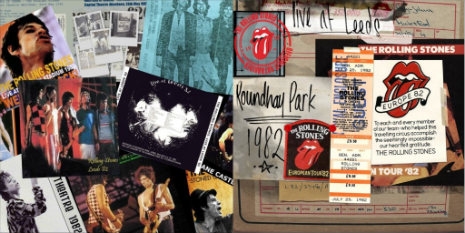

But let’s go back to 1982, when Kershaw was working for The Rolling Stones, as Andy explains by way of introduction to this extract from No Off Switch:

I had been, for the past two years, the Entertainments Secretary of Leeds University, booking all the bands and organising and running the concerts, at the largest college venue in the UK. Although non sabbatical and unpaid, I devoted all my time and energies to the job. We enjoyed a reputation - among bands, booking agents and management companies - as a highly professional operation with a long and rich history of running prestigious gigs. I had built up a good working relationship with the major UK concert promoters and, with my Leeds University stage crew, I was often hired by those companies to work on big concerts elsewhere. In the spring of 1982, I took a call in the Ents Office in the Students’ Union, from Andrew Zweck, right-hand man to Harvey Goldsmith, the UK’s biggest concert promoter at the time. “Andy,” said Andrew. “Would you like to work for the Rolling Stones this summer? And could you bring Leeds Uni’s stage crew with you?” Al, referred to in this extract, is Al Thompson, my friend and right-hand man in running the Leeds University concerts. Now read on…

The Rolling Stones Guide to Painting & Decorating

Already the size of an aircraft carrier, the stage was only partially built when we arrived.

Members of Stage Crew, like the remnants of a rebel patrol, were threading their way down through the trees, into the natural bowl of Roundhay Park, and gathering behind the vast scaffolding framework.

A couple of dozen articulated lorries, and a similar number of empty flat-beds were parked up in neat lines. More were rumbling into the park.

We squinted up at the riggers, chatting and clanking, swinging and building, climbing higher on their Meccano as they worked.

“Fuck,” said Al. And we all concurred with his expert analysis.

It was an impressive erection, even for Mick Jagger. And, at that time, the biggest stage that had ever been built, anywhere in the world.

Roundhay, in Leeds, in front of 120,000 fans, was to be the final date on the Rolling Stones European Tour, 1982, which broke records, set standards and established precedents on a scale never seen before. The logistics alone were mind-boggling.

If the scale of the infrastructure being unloaded before our eyes in Roundhay was extraordinary, there had to be - for the Stones to play a handful of consecutive dates in new locations - three of these set-ups on the road, and leap-frogging each other, at the same time: one under construction, a second ready for the gig; and a third being dismantled following the previous performance. We were just a fraction of the total operation.

To meet the backstage requirements at Roundhay, I was to be in charge of those logistics and grandly titled, for the next three weeks, Backstage Labour Co-ordinator.

It was reassuring to find a couple of familiar and friendly faces in the Portakabin offices which had been plonked down overlooking the grassy slope of what would become the backstage area. Andrew Zweck from Goldsmith’s office, and Harvey’s earthly representative during the build-up at Leeds, is a bluff, blond Australian with a reputation for getting things done. Uncommonly, for the music business, Andrew is good-humoured and devoid of self-importance. Similarly, Paul Crockford – Andrew’s assistant for the Roundhay gig.

Dear old Crockers was about the only bloke in the music industry that I actually considered to be a pal. Just a few years old than me, and a former Ents Sec at Southampton, he was now working in a freelance capacity for Harvey Goldsmith’s concert promotion company.

A tour of the Rolling Stones magnitude had required the UK’s biggest promoter to be co-opted as the British servant of the the overall mastermind of the enterprise, the legendary hippy impresario and pioneer, Bill Graham. In fact, this Rolling Stones adventure – taking in Europe and the States over two years - was the first time one promoter had staged a whole tour, globally. Graham’s experiment with the Stones, in 1981-2, would become the model for the industry in years to come. For the moment, however, in this previously uncharted territory, Graham and Goldsmith were making it up as they went along.

Crockers - even when he was ripping me off, selling me bands for the University - is always huge fun. Like Andrew Zweck, he doesn’t know how to be pompous. And like me, Crockers is amused most by the ridiculous and the absurd. This was to be a quality we would find indispensable over the following couple of weeks.

“That’s your desk,” said Andrew, pointing to a freshly-acquired bargain, in simulated teak finish, from some second-hand office supplies outlet. My position was in the middle of our HQ, handily by the door, and with a window overlooking the side of the stage and the slope leading down to where the dressing rooms and band’s hospitality area hadn’t yet been built. I could keep an eye on everything.

Crockers dumped in front me a telephone, a heavy new ledger and a cash box containing five hundred pounds before briefly outlining the mysteries of double-entry book keeping.

It started to rain.

A stocky, bearded little bloke soon popped up at the door.

“Hey, you,” he said. “Who’s the guy around here in charge of all the purchases.” The accent was American.

“Me,” I said. “Mine name’s Andy. Who are you?”

“Magruder,” he snapped, as though he was a brand. And one that I should recognise.

“What’s your job here?” I asked.

“Site Co-ordinator, Rolling Stones.” It crossed my mind it was unlikely he’d have been there for The Tremeloes. “Get me fifty pairs of Hunter’s boots and fifty waterproof capes,” he snapped.

And he was gone.

I’d not heard of this aristocrat among wellingtons before, but I packed Uncle Al off in his car, with a wad of the cash, to go and find fifty pairs of them around Leeds.

He returned with a full load of alluring rubberwear. And we stashed it all in one of the shipping containers that became our stores. The shower which had so alarmed Magruder soon passed. And the wellies and capes remained untouched, and forgotten, for the next two and a half weeks.

If it wasn’t Magruder himself who appeared at my door, there was a wealth of other petitioners, day and night, appealing for building materials and plumbing supplies. The latter were the requirements of a team of temporary toilet specialists - to a man polite, cheery lads with fruity Somerset accents - marinaded, for a fortnight, in human filth and who we branded the bogtricians. They were proud to tell everyone that, on his recent UK appearances, they had “just done the bogs for the Pope.”

Crockford’s initial float of five hundred quid quickly began to look like a laughably trifling sum of small change. Soon there were thousands crossing my desk, in cash, hurriedly noted in my ledger, handed to runners and enriching, within the hour, the city’s economy.

The source of most supplies was an extraordinary hardware store, of Al’s discovery, in the Harehills district of Leeds, called Stanton’s. Nothing remarkable to look at, mind you. Stanton’s exterior – a few plastic buckets, galvanised bins and a range of step ladders out on the pavement – did not suggest it had cellars going down two levels and more stock, no matter how arcane the item, than a B&Q national distribution facility.

If, at the counter of Stanton’s, one were to ask, “Have you a three-quarter inch thrust-grommet, please, for a 60 degree inverter?” Mr Stanton would possibly respond, “Weldon shank?”

“No. It’s the old screw shank model.”

“Not to worry, sir. The screw shank did have its merits. Is that with or without the retaining flange? With, is it? Very good. Do bear with me, sir. I know there’s one here somewhere”

Or, equally, “I wonder if you have, please, an extended undercut lay-shaft (coarse-toothed), with drive dogs?”

“Helical gear?”

“Bevel gear.”

“With bushes?”

“Yes, please.”

“Plain or roller?”

“Er, roller, please.”

“Certainly, sir. Just the one, is it? There we are.”

After a few days, it became clear to me and Al that the Stones gig was dependent entirely on Mr Stanton’s remarkable little shop. With others, Al had been operating an almost constant shuttle service between Harehills and Roundhay since my rebirth as Quartermaster to the Stars. Work was going on around the site 24 hours a day. Stuff was always needed.

“Al,” I said one afternoon, about a week before the gig. “Stanton’s not being open is unthinkable. What’s more, with the day of the concert being a Sunday, suppose we need something vital from Stanton’s then?”

Al took off again to see Mr Stanton, this time with a business proposal and a bundle of readies.

“No problem,” he reported when he returned. “Stanton’s will be on call, around the clock, until a week on Monday.”

In all seriousness, The Rolling Stones Roundhay mega-concert could not have happened if Mr Stanton, handsomely bunged, had not become the pioneer in Leeds of 24 hour shopping.

“Hey, you.” It was my friend Magruder again. Winning hearts and minds did not seem to be his mission in Roundhay. “About this fence…”

“What about the fence?”

“It’s the wrong fucking colour.”

The fence which was offending Magruder was the perimeter fence of the site. Ringing the bowl, forming the arena, it had been built with sheets of heavy plywood, about ten feet tall, bolted to scaffolding pole supports.

“Well,” I said, “it’s plywood colour.”

By now, Magruder and I were standing in the centre of the battleship stage, gazing out at the distant barrier.

“It’s gotta be green,” said Magruder.

“Any particular shade of green?” I asked.

“Grass green, of course.”

In the Yellow Pages, I found a paint company in Batley. Not a shop. Not even a trade outlet. A factory which made paint.

A patient chap there listened to my requirements.

“But there’s no recognised shade as grass green,” he said.

“Oh, isn’t there? Well, never mind. You get the idea. As long as it’s green. Like grass.”

“So this fence is ten feet high, you say. And how long is it?

“About a mile,” I told him.

There was a pause.

“I see,” he said.

The next day a couple of flat-beds arrived, laden with drums of green paint. I got the drivers, with Stage Crew’s help, to dot them along the perimeter of the fence. With rollers on long poles my lads set to work. They got it done impressively quickly. I was proud of them.

Magruder was at the door. “It’s the wrong fucking green!” I swivelled in my chair. Together we marched back to the stage.

“That’s not grass green. It’s too dark.”

I had nothing to say.

“Do it again. Get the paint guys to add some blue.”

I jumped. “Eh? That’ll make it even darker. You mean add some yellow.”

“Look. I mean what I said. I know what I’m talking about. That’s why I’ve got my job and you’ve got yours. Add blue.”

I phoned my man in Batley.

“That’ll make it even darker,” he said.

“I know. I’ve told him that. He won’t listen. He’s insisting on a new batch. With added blue.”

The flat-beds returned. With drums of blue-enriched Magruder Green. Stage Crew got to work.

“It’s fucking darker!” Magruder was squawking.

“I know. That’s what I told you.”

“Okay, okay. Yellow. Get the yellow.”

“How about I send you one load of yellow?” suggested Batley’s new leading fence-camouflage consultant. “Get your lads to mix it into that last batch of green.”

The yellow arrived. Stage Crew tipped it in and applied the fence’s third luxurious coat.

For the next inspection, a top-level site meeting was convened on the stage, now also involving Crockers and Zweck, who had begun to notice The Rolling Stones were spending thousands on emulsion.

Magruder, ever the perfectionist, was not going to compromise.

“That still ain’t grass green. It’s gotta be done again, until they get it right.”

We were back, pretty much, to the shade of the original offending coat.

Crockers and Zweck, who were newcomers to Magruder’s spectrum sensitivities, tried to soothe him with platitudes and deferential assurances that everything would be fine.

I’d been wondering how long it would be before Magruder, in this week-long debate over exterior decoration, invoked a personal relationship with the Rolling Stone in Chief.

“If that fence is still that goddam shade of green when Mick gets out here on Sunday, the Rolling Stones will walk off this stage” he snarled.

“Dear me,” I said. “And who will explain to 120,000 fans who’ve bought tickets why there’s no Rolling Stones concert? Mick himself? You? Or would you like me to tell them? That it’s all about that plywood being the wrong colour.”

The fence was not mentioned again. Attention instead switched to the Japanese water garden.

“What Japanese water garden?” I asked.

“They want us to build one.” A delegation from my Stage Crew had gathered at the door. “They want a stream, a bridge, a waterfall, a pond and koi carp.”

“Stop!” I said “What for? Where, ferfuckssakes? And when?”

“In the Stones dressing room. By Sunday.”

The Rolling Stones dressing room was more of a leisure complex. And what estate agents like to describe as “executively appointed”: individual suites for each band member, over which was flown a big marquee, creating a hidden compound with its own communal area for mingling, fine dining and entertaining. The water garden was to be its centrepiece. We had three days to get it done. After sourcing the components.

I beetled off to Roundhay’s Parks Department site office where I found two nice old boys drinking tea and watching the comings and goings out of the window. I explained my predicament.

“Oh, aye?”

There was some discussion about rocks, waterproof linings and pumps. At their suggestion, a few plants in tubs were added to the list. And water-lilies. Yes, they could help. (As I’d been finding, the bundle of free tickets for Sunday’s concert, in my pocket, helped to overcome any inertia). And as for the fish, wasn’t there - one of my new friends wondered - still that supplier over Harrogate way? Not to worry, lad. They’d get everything dropped off, probably tomorrow.

Back at the Portakabin, no demands from the Stones representatives – however preposterous – could now faze us.

“Find me someone who can write Japanese.”

“Get Bill Wyman a masseuse for Sunday.”

“We need a ton of dry ice. Now.”

The communal area of the dressing room - now alive with Stage Crew, multi-tasking as hydrologists and landscape gardeners, and working out the plumbing of an artificial stream - was to be dotted with tables, chairs and parasols. On these parasols, someone in the Stones camp had decided, it would be appropriate to have painted, “Welcome, Rolling Stones.” In Japanese.

I phoned the School of Oriental Studies at the University. Would they have a student who, for a couple of Stones tickets, might be willing to come down and carry out this calligraphy? They called back. Yes, they’d found a girl who’d do it. I sent over a car to pick her up.

“About this masseuse,” I murmured to Crockers in the office. We were gazing out of the window at the efforts of a man called Graham ‘Nipper’ Dixon, who enjoyed the position of Rolling Stones Balloon Co-ordinator. For some days now, Nipper and his team had been inflating thousands upon thousands of helium balloons and storing them in a couple of giant nets at both ends of the stage.

“If I were to phone a masseuse in the Leeds Yellow Pages, Bill Wyman would be getting more than his back rubbed.”

Then I remembered my friend Maggie. A schoolteacher in Headingley, Maggie was New Age before the syndrome had been identified and classified. She subscribed to all manner of mumbo-jumbo: alternative remedies and other nonsense which, over the centuries, had been tried, dismissed and eliminated as treatments - because they didn’t work - leaving us instead with science, medicine and drugs. Maggie burned a lot of joss sticks. She was bound to know someone who did massage. Probably with combined aromatherapy.

And she did. But they were away.

“You can do it Maggie,” I said.

“No, I can’t.”

“Of course you can. Just pummel his back a bit. Squeeze his muscles. Rub him up and down. That sort of thing. He’ll never know the difference.”

I promised a bundle of tickets and said I’d send a car on Sunday morning.

“Oh, fackin’ ‘ell!” The man who was addressing us was Harvey Goldsmith himself. He’d arrived to supervise matters, just the day before the show. Now he was occupying the desk at the far end of our office. It was the morning of the gig. And he’d covered his face with his hands. Someone asked what was wrong.

“I’ve forgotten the fackin’ guest passes.”

Looking down the office, I took stock: the world’s two biggest promoters in the same hut; Goldsmith at the far end and at the desk on my left, in shorts and sandals, suntanned and on the phone, was a genuine living legend - Bill Graham, a man whose initiative and enterprise had shaped the course of rock & roll history.

Together, they had a little problem. And I had a solution.

Eighteen months earlier we’d put on Dire Straits at the University. My printers had assumed I’d made a spelling mistake on the order for the backstage passes. They took it upon themselves to correct this. When they delivered them, I’d explained they’d been too literal and I got them to print a new batch. Consequently, in my drawer in the Ents office, I still had a brick of about 200 unused, and I thought useless, stick-on passes. It was lucky I hadn’t thrown them in the bin.

“They’ll do!” said Goldsmith, when I told him.

I sent Al across town to fetch them.

So it was, when the Rolling Stones After Show guests - not a party, one would imagine, noted for self-deprecation - were floating around the backstage area and in and out of the Japanese hospitality garden, they did so enduring the indignity of having to have slapped on their chests stickers celebrating “Dire Straights”.

By mid morning, the guest passes were the least of Harvey’s worries. He’d been on the phone and turned to us as he put down the receiver.

“The Stones are stuck in traffic.”

Traffic? I’d assumed they’d be helicoptered in, possibly from a rented country house in the Yorkshire Dales. But no. Again, it was the consequence of unavoidable inexperience, of staging an event unprecedented on this scale. The Stones had stayed in a Leeds city centre hotel, were coming up from town in a bus and were now democratically grid-locked along with – and because of – their own fans. Everyone, including the band, was on the way to Roundhay. All at once.

George Thorogood & The Destroyers and The J Geils Band kept the early arrivals distracted, giving the Stones the opportunity to take in many of Leeds’s attractive north-eastern neighbourhoods.

I could sense the moment they’d finally arrived on the premises. Magruder and his American colleagues became even more manic and self-important.

Now, a man was bellowing over the immense PA system. An ocean of humanity was roaring back. The flaps of the Stones canvas compound were drawn open. A white limo reversed in and then emerged, seconds later. It crawled up the grassy slope, fully fifty yards to the steps of the stage. Out swung Jagger, followed by Charlie Watts, Ron Wood and Bill Wyman. Jagger, in a sky blue lycra jogging suit, began bouncing up and down on the bottom step. Someone was missing.

The announcer’s voice was rising. “...ladies and gentlemen, The Rolling Stones!”

A hurricane of euphoria swept the bowl. It said thank you, simply for surviving. Mick Jagger had turned 39 that morning. I heard the deep boom of explosions. Nipper Dixon liberated his balloons all at once, pink and blue, his week’s work. They climbed and darkened against the clear afternoon sky, like a swarm of starlings, and floated off to litter much of West Yorkshire. Jagger jogged up the remaining steps, Watts, Wood and Wyman clomping steadily behind.

The flap of the marquee this time snapped back. A tall, angular figure – a black and white cartoon – stepped forth, alone. He had implausibly long, thin legs. A fag was jammed in the corner of his mouth. By the neck, he gripped a Fender Telecaster. He grinned at well-wishers. In what seemed just half a dozen long strides he was at the top of the grassy slope and on the stage steps.

Despite the best efforts of the the Stones corporation over the previous fortnight, my faith was instantly, warmly restored. By the sight of a humble craftsman going to work.

The shapeless rumble of outdoor rock music solidified into something recognisable.

“Under mah thumb…”

I turned to Crockers and deflated in my swivel chair.

“Thank fuck for that.”

Maggie popped her head in at the door.

“How did it go?” I asked.

“Fine,” she said. “He said it was great. One of the best he’s had.”

I went for a wander and watched a couple of numbers through the side of the stage: Jagger pouting and peacocking on the platform of a cherry-picker; Jagger, high above the crowd, wiggling his bottom from the bucket of a crane. I felt the urge to buy his band members a pint.

“Hey,” said Crockers, “did you manage to get that Japanese writing done on those umbrellas?”

“Oh, yes.” I said. And smiled my secret smile.

But it wasn’t until a couple of years later, over a drink in London, that I told him the full story.

We were standing - the sweet child from Oriental Studies and I - by a chortling brook in the Stones hospitality area. She had a box of brushes and some ink.

“Thank you for helping us out,” I said and handed her a pair of tickets for Sunday’s show. “And there are two more for you here if you wouldn’t mind amending slightly the message on the parasols.”

I explained the minor rewording. She dimpled shyly but said she’d do it.

When Jagger and the band were later luxuriating, post performance, in their indoor oriental garden, with their friends perhaps lingering on the delightful bridge to remark on the koi in the pool below, I trust they also admired the parasols. For each was decorated exquisitely with the hand-painted greeting, in Japanese: “Fuck you, Rolling Stones.”

Extracted with permission from Andy Kershaw’s brilliant autobiography No Off Switch. Order your copy here, or on kindle.

For more information about the legendary Andy Kershaw check his website.

With kind thanks to Andy Kershaw