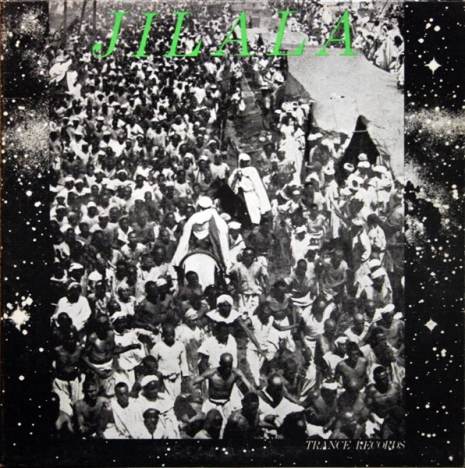

Part of Ira Cohen’s layout for the Jilala sleeve (via Granary Books)

Brian Jones Presents the Pipes of Pan at Joujouka was not the first album of Moroccan music inspired by the kif-smoking literary expats in Tangier. In 1964, Brion Gysin and Paul Bowles taped the Jilala brotherhood, a Sufi order whose ritual dance and music were supposed to exorcise evil spirits and heal the sick. The LP Jilala, released a year or two later by Ira Cohen, brought these recordings into limited circulation and preserved them for posterity.

Poet, musician, traveler, author of The Hashish Cookbook, and director of The Invasion of Thunderbolt Pagoda, Cohen was another Olympian of the arts who had joined Burroughs, Gysin, and the Bowleses in Tangier in 1961. (My old employer Arthur Magazine brought out Invasion of Thunderbolt Pagoda on DVD ten years ago, with new scores by Acid Mothers Temple and Sunburned Hand of the Man supplementing the original soundtrack by founding Velvet Underground drummer Angus MacLise.) Years before his psychedelic photo experiments with Mylar, Cohen edited the literary magazine Gnaoua, named after a form of North African religious music that’s related to but distinct from the Jilala’s.

It’s not entirely clear how Jilala is connected to another Paul Bowles recording project involving the same collaborators, time, and place. Bowles wrote Cohen in 1966 about donating the profits from something called the “Hypnotic Music record” to the Timothy Leary Defense Fund. In a footnote, the editor of Bowles’ letters says this refers to a compilation of Hamatcha, Jilala, Gnaoua, and Aissaoua trance music that was put together from tapes made separately by Bowles, Gysin, and Cohen and released by Cohen. However, the Independent reports that the Hypnotic Music record was an unrealized project, so perhaps Bowles’ editor has conflated it with Jilala, which Discogs lists as the sole release on Cohen’s Trance Records.

I would be delighted to be proven wrong about this. Does anyone have a copy of the Hypnotic Music record?

The cover of the original issue of Jilala

Before putting Jilala in your gym playlist, you should probably read Cohen’s liner notes (reprinted in full at Big Bridge and Discogs) so you know what you’re getting yourself into. The Jilala knew how to pitch a wang dang doodle with their flutes and drums. The bath salts of their day, these religious tunes have been known to make listeners eat live animals, slash themselves with knives, and drink boiling water straight from the kettle, as Cohen tells it:

The Jilala, like the other religious brotherhoods of Morocco, is probably rooted in pre-Islamic ritual and celebration, but it is at the same time definitely a part of the great Sufi tradition of the Middle East. An off-shoot of the Kadiree order which was begun in Baghdad in the twelfth century by Moulay Abdelkader Ghailani or Jilali as he is often called in the Maghreb-the Jilala is an order of dervish musicians known for their practice of trance dancing and spiritual healing. They are called upon to exorcise evil spirits and to purify the heart. The Jilala are particularly useful in curing cases of epilepsy and hysteria, controlling the spirits or demons in possession of the subject through their music and the ritualized gestures of the dance. But mainly the dances are dances of exaltation. Paul Bowles writes in a short story, The Wind at Beni Midar, “A Jilali can do only what the music tells him to do. When the musicians play the music that has the power, his eyes shut and he falls on the floor. And until the man has shown proof and drunk his own blood the musicians do not begin the music that will bring him back to the world.”

The dancers come as they are called by the music; and their number varies with the size of the gathering and the place, including both men and women, the very old and the very young. Incense is burned throughout the evening; and the smell of black jowee or benzoin heightens the trance state and is often used to revive a dancer who has passed out. The women characteristically weave and bob back and forth to the music, spreading their arms and then crossing them over their breasts. As the tempo increases they throw their heads back, their faces showing mingled ecstasy and pain, harder and faster, their long blueblack hair unloosened and flying across their faces. The men more typically bounce from one foot to the other slashing at the air with their hands, or with arms outstretched gliding in circles moving from one leg to the other until fingertips nearly touch the floor. The highest moments proceed from the reciting of the zikr or repetition of the name of Allah and his epithets. At the very peak of intensity special acts are done as part of the dance. Slashing arms and legs with sharp knives, or laying down hard with a heavy belt on an extended forearm or across the back are an accepted part of the ritual. Sometimes a dancer will take off his turban and wind the cloth around his waist, giving each end to a fellow Jilali who then pulls as hard as he can until the dancer is lifted off his feet and begins to turn in the air. Live animals are known to be devoured in the trance state, and red hot coals are often handled without injury as a proof of faith and power. One member of the group once pressed his bare foot down into a heap of flaming coals for several minutes before dancing a special number devoted to their lame patron saint, Moulay Abdelkader Ghailani. During the first selection on the second side of this recording Farato, the fire-eater, drank a kettle of boiling water, eliciting from the women a wild burst of yu-yus.

Not everything is on YouTube. If you want to be driven to sacred madness by Jilala, you’ll have to get a used copy on CD or vinyl. Instead, here’s Bowles’ recording of a Jilala wedding procession from a 1990 compilation of Gnaoua and Jilala music. “The end of this track sounds like Stravinsky to me,” Bowles said, referring to the admixture of car horns.

And here’s a 1993 interview with Bowles about his ethnomusicological work in Morocco. Earlier this year, Dust to Digital released a beautiful box set of the Moroccan recordings Bowles made for the Library of Congress in 1959.