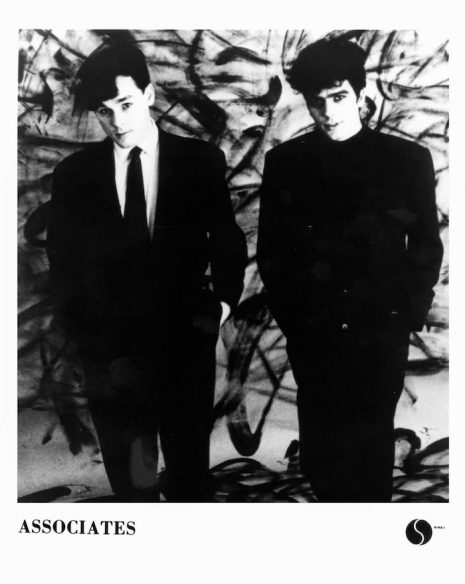

The Associates were a band that should have conquered the world. In fact they almost did. They had the music in them and a sound that was uniquely their own. Formed in 1976 by the dovetailed talents of musician Alan Rankine and singer Billy MacKenzie, The Associates produced three first class albums between 1980 and 1982: The Affectionate Punch, Fourth Drawer Down and the magisterial Sulk. They had a clutch of hit singles and a fanbase that believed The Associates were the future of music.

Then, at the height of their fame in 1982, it all fell spectacularly apart on the verge of a million dollar record deal and their first world tour. Rankine quit. MacKenzie carried on as The Associates. Neither quite ever reached the creative highs and popular success they had so easily achieved together. This is Alan Rankine’s story of The Associates—egg-slicers, chocolate guitars and the legendary Billy MacKenzie.

It could have been all so very different.

If Alan Rankine had been a few inches taller he could have been a tennis player. A world class tennis player. A champion. Hitting grand slams for breakfast.

“When I was nine, ten, eleven, twelve, thirteen, I was heavily into tennis. I was really, really into tennis. Big time. I was beating people when I was twelve and they were sixteen. I was really pissing them off—especially when I was beating them in front of their girlfriends.”

Winning was easy for Alan—but he became aware he had one fatal drawback to ever making tennis a lifelong career.

“I was a midget. I was a bit of a shortarse. I could see the writing on the wall—as tennis got more powerful because of the rackets and the strength of the rackets—no one was going to win anything unless they were six foot two. I was never going to be more than five foot eight, and I was proved right.”

Rankine dropped tennis and started looking for something else, something better to master. He liked the guitar. Beat bands were in—The Beatles, The Stones, The Who—so playing guitar seemed the obvious thing to do.

“I remember I annoyed the hell out of my father. You know these little egg slicers you get that’s got a scooped out bit for the egg and it’s got ten strings? Well, I’d go around the house behind him plucking on this thing—Buy me a fucking guitar, buy me a fucking guitar—annoying the hell out of him for weeks. ‘Okay, okay, anything to make this stop.’ On my eleventh birthday he got me a guitar.

“It just seemed right. I started playing the guitar the whole time—I just never stopped. I was either playing along to records or playing along to the radio—just switching between channels and listening to everything. Then I got an electric guitar, then a better electric guitar and just kept on going and going and going. It just seemed easy.”

As he had found with tennis, Alan had a natural talent for the guitar. He practiced in his room for six hours at a time getting the songs he liked down pat—until he could play them note perfect.

“Pretty soon I moved on to my granny’s piano—Christ, this was easy too. I thought this was the way it was for everyone. It was just so easy.”

His father could play the violin. Badly. His uncle played French horn with the Royal Scottish National Orchestra. There was no other notable musical talent in the family—that is until Alan picked up the guitar. It was the first move towards his legendary career as one half of The Associates.

Alan Rankine was born in Bridge of Allan, Stirlingshire, Scotland in 1958.

“I stayed in Dundee from the ages of five to twelve. I stayed in Broughty Ferry—the posh part. Then I came to Glasgow, Newton Mearns—the posh part. Then Linlithgow—fairly posh.

“My dad always used to ask me—‘Who are you playing with? Where do they stay? Are they from council houses?’ I got this the whole time—he was always very, very protective. But I always seemed to gravitate to the people from the council houses.”

“I was in Linlithgow. I was fifteen years old. As you do when you’re fifteen turning sixteen you try and get into certain pubs because you want to be a man and have a pint and all that stuff. And there were certain pubs out of the twelve or thirteen that went along the one main street in Linlithgow where you could go and you know a nod’s as good as wink and get served.”

“I went into one and there was a band playing. I said, ‘Christ that guitar is shit.’

“I went up to the lead singer after their set—they’d been playing all this Steely Dan stuff—and I said, ‘Your guitar is shit.’ He must have thought, ‘What’s this little cunt coming up to me and saying this for?’

“I said, ‘Look, come up to my house tomorrow.’ He came up to my house and I just ripped off “Kid Charlemagne” and all these Steely Dan numbers. Note perfect. Sound perfect. Everything. I got the job with that band.”

Alan’s first taste as a gigging musician was playing cabaret clubs and miners welfare clubs. He moved to Edinburgh. Every week on a Sunday the band learned to play six new songs—chart songs, hit singles, stuff from the catalogs of Burt Bacharach and Jimmy Webb. When not playing the cabaret circuit, the band was booked for “real gigs as a band” playing some clubs across the city.

“These other people in the band—no detriment to them—they were into Yes and Genesis and it was all too much wanking your plank to no avail.”

“If you’re going to do something have a point. I’m reminded of that line when Steve Martin said when he was berating John Candy in Planes, Trains and Automobiles: ‘And by the way, you know, when, when you’re telling these little stories, here’s a good idea. Have a point. It makes it so much more interesting for the listener!’”

Not long after he joined, the band’s lead singer went “a bit loopy.” The search for a replacement brought Alan to a club in Edinburgh where he heard this voice—this utterly amazing voice. The club was jumping. Alan was at the bar and couldn’t see beyond the dozens of people crowded around the stage—faces upturned, happy, joyous, glistening with sweat watching the singer on the stage: a young man called Billy MacKenzie.

“I got the person who was booking our gigs to contact the person who got that gig for that venue. Within four days of that call, Bill was getting out a taxi in Edinburgh. Two days after that he staying on the sofa bed in my girlfriend’s and I’s flat in Edinburgh.

“We just hit it off like that.”

Billy MacKenzie was born in Dundee in 1957. He was one of those wild boys Rankine’s father warned him about. At just nineteen, MacKenzie had already experienced a far more exotic and adventurous life. He quit school at sixteen. Moved to New Zealand then Australia. Worked as a driver of forklift trucks (“Can you imagine Billy doing that?”). At seventeen, he traveled to America where he outstayed his travel visa. In order to stay longer in the States, Billy married a young woman called Chloe Dummar—the sister-in-law of one of his aunts. He described his wife as “a Dolly Parton-type.” Billy later claimed that during their wedding ceremony the minister spent most of his time flirting with him. The marriage didn’t last. Billy returned to Scotland and rekindled a childhood passion for singing. He joined a band and started gigging across the country.

Billy was a star. He was camp. Fey. Beautiful. With the voice of an angel.

Sitting in the large front room of his tenement apartment in Glasgow’s wealthy West End, Alan is older, wiser. He sits on a large sofa, his back to the sunlit windows, a view onto the quiet leafy road outside. He is stylish—has close cropped hair, wears a grey knit pullover, smokes Rothmans. To one side a bookcase, fireplace, mirror, mementoes. To the other a large TV, a display of musical instruments—guitars, electric, acoustic, and a banjo. Behind me a keyboard and a large Mac computer on which he writes and records music. Throughout our interview his conversation is punctuated with laughter. He is funny, wry, and genuinely likeable. He talks about his former musical partner the late Billy MacKenzie with great warmth, deep affection, considering his words thoughtfully before talking about him. Yet, for all the love and admiration, there’s a lingering sense of sadness over The Associates split at the height of their success in 1982.

It could have been all so very different.

“When Bill first came down to Edinburgh he had to stay with these self same musicians I was playing with. I was living with my girlfriend. Bill had to stay with nine guys. Four up in the mansard roof and five guys down below in this flat in the Marchmont area of Edinburgh. After two days Bill said to me, ‘Man, you gotta get me outta here, I cannae fuckin’ take it. There’s too much testosterone.’

“I could see the desperation on his face—he just couldn’t handle it. I said, ‘Okay. Look here’s sanctuary here.’ From that point on we just wrote and wrote and wrote.”

Their tastes matched. They both liked Bowie. They both liked Roxy Music. They both liked Marc Bolan. They both like Serge Gainsbourg. Add to this: MacKenzie had a passion for Billie Holliday—he had been “steeped in it. You can hear it in his voice.” While Rankine liked John Barry and Ennio Morricone—“the usual suspects.” All these flavors were to filter into their songwriting.

“As soon as Bill and I started writing songs together that existing band we were in—that were into Yes and Genesis, Emerson, Lake and Palmer and everything that we couldn’t stand—we just separated ourselves from them.”

They moved to Alan’s home where they spent their time writing and recording songs on a tape recorder.

“Nothing was contrived. We didn’t say, ‘Let’s aim to do that.’ Sometimes we said, ‘Let’s aim to do that’ for a laugh, but there was always an ulterior motive to it. It was what just came out.

“You can listen to our first album Affectionate Punch—there’s ten tracks and lyrically Bill’s wanting to do a play on words thing. He used to play on words an awful lot. I had to say to Bill early on in ‘76 and ‘77, this is too obvious, man, this is too much I’m doing a play on words, I’m doing a spoonerism or a malaprop or whatever. That’s too obvious you’ve got to conceal. Be a little more subtle.’

“A lot of his songs are about his struggling with his gender and his sexuality.”

As a duo—an awful lot of what they wrote came out of necessity as they knew they would have to play these songs live.

“We knew we couldn’t play all of them because a lot of them had keyboards and we never had any intention of going out with keyboards—it was always going to be very, very stripped back. So I had to make the biggest sound possible.”

The Associates sound didn’t fit the punk and post punk years between 1976-1980—they were writing songs that were three-four=five years ahead of what was then current—The Jam, The Clash, and Two Tone. Bill and Alan never doubted their time would come. One song in particular they wrote during those early days only confirmed they were on the cusp of good things.

“Party Fears Two that piano motif that was written in ‘77. I did that on the piano. I hit a wrong note. There was something about it. I was suddenly in the key of G going E, D, A minor then F major. And Bill and I immediately looked at each other—That’s gold.

“We knew we couldn’t use it because all that was around at that time was punk, post punk and disco. It didn’t fit. We had to sit on that song for four years before we recorded it—but we knew that song or that motif would be what got us signed and we knew that would be our first single.”

The Associates continued their intermittent appearances on the cabaret circuit.

“You’d see all these punk bands every night in Nicky Tams [a club] in Victoria Street, Edinburgh, being shit and coming back five weeks later having changed their name and still being shit.

“We thought, ‘Fuck that.’ We got ourselves a residency at an hotel and that gave us a changing room and a room in the hotel so we could fuck whenever we wanted. We could get free food from the hotel. Free beer from the hotel. And on the other nights we would go to miners’ welfare clubs. In the hotel we would play music—which was so quiet that you could talk like we’re talking now and still be heard. Then you’d go to the miners’ welfare club and all the guys would be up the back getting flipping bladdered and all the women would be down the front trying to get into Bill’s pants.”

By 1979, they had written enough songs for their first album. They were attached to Fiction Records but their recording career was going nowhere. The label didn’t know what to do with them, didn’t know how to package them, didn’t know if they really wanted to sign them—they were “dithering about.”

Bill and Alan decided to kick start their recording career. They recorded a cover of Bowie’s latest hit single “Boys Keep Swinging” in June 1979—just six weeks after Bowie had released it.

“It just nudged into the indie charts—we only made about 500 or a thousand copies, I can’t remember. Bill’s dad paid for that. Bill’s dad paid for the studio, the production time, and all the rest of it.”

It wasn’t long before one of Bowie’s people (“You got the feeling he wore Gucci underpants”) got in contact and said “You’ve been a bit naughty.” Rather than proceeding with any legal action it was decided The Associates should sign to MCA Records. This duly happened but by some strange machinations The Associates were with MCA for only six weeks before they were back with Fiction Records again. Rankine is still bemused by this.

“I don’t know how that went. It was like there was old favors being done between MDs of record companies and publishing companies and we were just being traded about. I don’t understand the machinations of it—that’s how it seemed because we got into a contract and got out of it in a matter of weeks with no ties. I don’t know what went down.”

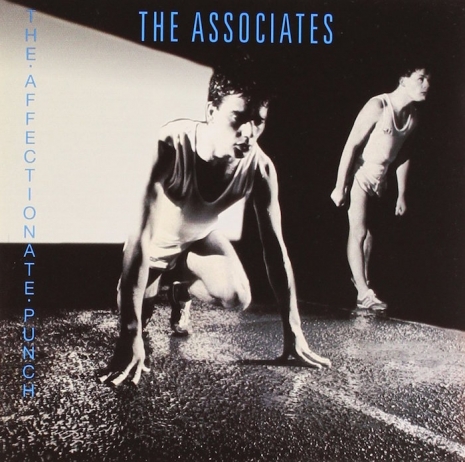

I first heard The Associates at party circa 1981. Someone had brought along a copy of their debut album The Affectionate Punch. It was put on the turntable. From its opening title track—everything stopped. People stopped talking and started listening. We thought—as many a young kid does—we were hearing the music of the future—“The Affectionate Punch,” “Amused As Always,” “Paper House,” “A Matter of Gender,” “Deeply Concerned” and “A.” Rankine’s rich, lush, driving music was beautifully complimented by MacKenzie’s powerful, dramatic and soaring voice. Hearing this album made us all fans of The Associates—and we played their album a lot that night.

Two months after they recorded The Affectionate Punch, The Associates played a small selection of gigs to promote the album. They brought in Michael Dempsey on bass player and John Murphy on drums.

“We only played three songs from that album,” recalls Rankine, “We couldn’t do the rest of the album because there were too many keyboards on it. So we had to write new songs.”

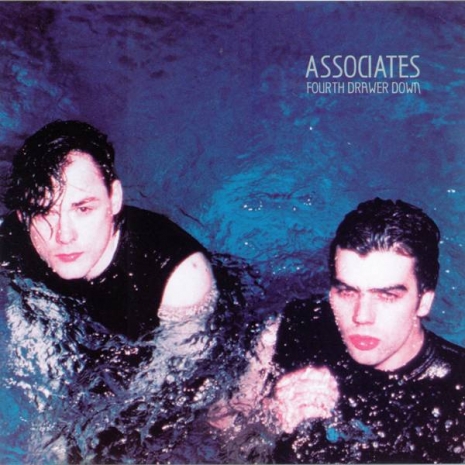

The Affectionate Punch was followed by Fourth Drawer Down—a collection of six singles recorded for the Situation Two label. This was a showcase compilation album that included such classic tracks as “White Car in Germany,” “A Girl Named Property,” “Kitchen Person,” “Tell Me Easter’s on Friday,” “The Associate” and “Message Oblique Speech.” It was more experimental but utterly compelling.

Between these first two albums The Associates had evolved musically and were moving in a far more exciting, new and creative direction than any of their contemporaries. But things weren’t going as well behind the scenes as Billy and Alan were living off their wits.

“First of all we got solely ripped off by Fiction Records. Now they had about four bands going—The Cure being their mainstay, if you like. They ripped Bill and I off good style. After we’d signed to them and after we had recorded The Affectionate Punch, sure enough about five months after that we said, ‘We’ve done all the gigs. We’ve toured Scotland. We’ve toured England. We’ve done London inside and out. You’re still shit. Can you please let us off your label?’

“So, the guy said, ‘Okay, hands up, we’re shit. But I still want to hang on to your publishing.’ Okay, fair enough. We were then staying in a flat in St. John’s Wood [London] which had been paid for in advance for about six months—so we had somewhere nice to stay but nothing to eat.

“Bill and I, although we were the ones who had signed we said we want to support the bass player and the drummer and our friend Derek who was with us at the same time. We were able to court all these major record companies coming to our flat. I think they were trying to puzzle out how are these guys affording this? At the same time we were doing that, we recorded all these singles for Situation Two. We would go into a studio at 9pm on a Sunday evening come out at 9am on a Monday. It cost us £100. We would go down to Beggar’s Banquet and we would get £3,750 from them every six weeks—that’s how we survived.”

“Then Warner Brothers waded in. You’ve got to remember Warner Bros. at that time in 1981 had Dollar, they had Modern Romance—they had nothing—apart from going through Bill Drummond and Korova Records and maybe Echo and the Bunnymen. But they had absolutely nothing that was cool. So, they gave us everything that we wanted.

“We said that’s fine—because we knew we would have three hit singles and a hit album.”

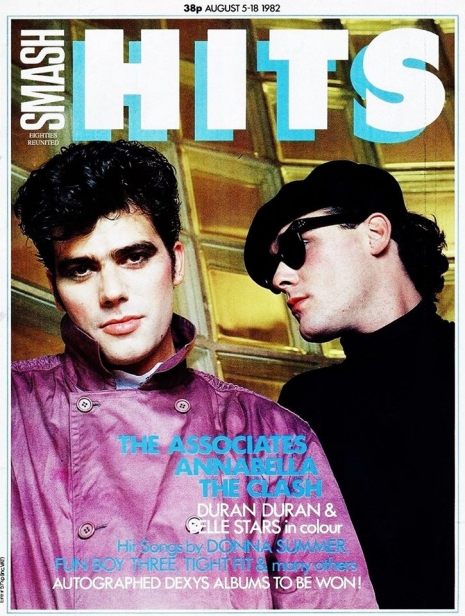

The Associates signed for Warners. They delivered their masterwork Sulk and three hit singles “Party Fears Two,” “Country Club” and “18 Carat Love Affair.”

The stories, myths and downright lies about the recording of Sulk have long been told—a profligacy of money spent on drugs and clothes and of guitars filled with urine—but the quality of songs and their exquisite production suggests The Associates were nothing less than hardworking perfectionists in the studio.

“People keep talking about us being profligate with money. Our advance for Sulk was £69,000. It wasn’t a lot of money. People in that day and age were getting signed for hundreds of thousands of pounds. We took the advance and wrote a check to Playground Studios for £30,000 so we had a block booking. That paid for about four months of studio time. We didn’t piss it away like everyone thinks we did. Yes, we had our little indiscretions if you like—experimented with the old Bolivian marching powder and the rest of it, but it was like a treat. It wasn’t something that added to your experience—it was like dogging school. It was like, ‘Well, we know we’ll get into trouble but fuck it.’ We won’t really get into trouble because it’s the end of term. It was that type of thing.

“We dabbled. Other bands were getting it in by the fucking kilo. But they had damage limitation—they had their record company and their PR people. Everything was like a wall was built up. All these Duranees and Spandaus, The Cure and Depeche Mode—they were flipping off their tits the whole time!”

February 1982: The Associates had their debut appearance on Top of the Pops. Compared to the other acts that night—or indeed any night—The Associates were in a different league. They launched into “Party Fears Two.” MacKenzie in his trademark beret and overcoat spent the whole performance gazing at himself in the TV monitors. Rankine for some reason was dressed in a fencing suit with chopsticks in his hair while playing the one instrument not included in the song—a banjo.

“Top of the Pops is boring so you try and make it as fun as you can. Hence the banjo and the fencing suit and the Japanese hairdo. Hence, the chocolate guitars. You’d just do anything to alleviate the boredom.”

Among the many jolly wheezes Rankine perpetrated on the show the most famous was the chocolate guitar he played during their appearance for “18 Carat Love Affair.”

“I got them made at Harrods they cost £220 each—I had two because with the super trouper lights it would melt. There was a thin bit of wood on the neck the rest was pure chocolate and the audience just ate it straight off me.”

“We were going to give out the second one as a fan club prize but the audience ate that too.”

Rankine also had a plan to perform from inside a portable Turkish bath “like the one in Thunderball” with “smoke machines inside pumping out the vanilla ice. It was a quiet way of saying ‘Fuck you’ because the BBC is so institutionalized.”

Rankine with his chocolate guitar.

The Associates were at the top of their tree. They were hailed by the music press. Had chart hit albums and singles. Had sell out concerts. The stage was set for a tour of America.

“There’s a certain hump bands have to get over and that hump is definitely America. If you don’t make it in America you’re restricting your market. The Who made it in America but that was at a time when 35% of all the records sold in America were British. Zeppelin, The Who, Black Sabbath, all these people. At the time when The Jam came out basically doing The Who again, they didn’t even travel to Europe. The Cure were supporting them and suddenly they were supporting The Cure, because The Cure traveled.

“Bands that crack America like Duran Duran are quids in. That’s what you had to do. There’s part of me that wishes we could have had a shot at cracking America.”

At a meeting a few weeks before The Associates started their first world tour, Billy MacKenzie made a devastating announcement.

“We had all these dates booked up. Not just in the USA but Canada and Japan—everywhere. We block booked Robert Palmer’s studio in the Bahamas for two months to do the fourth album. How the hell were we going to do that? We hadn’t really thought that through.

“Bill sat down at a table at Langan’s Brassierie with the head of A&R at Warner Bros. Seymour Stein and he said ‘I dinnae want tae dae it.’”

Rankine laughs at the audacity of MacKenzie’s actions. It wasn’t just a tour MacKenzie was knocking back but a £900,000 (around $1.5million) record deal with Sire Records in America.

“Seymour almost choked on his quail’s eggs. That was it. There was no way back.”

Alan pauses for a moment thinking back to that fateful lunch.

“I think Bill wanted to stretch his legs. When Bill and I and Dempsey and Murphy were playing we decanted ourselves to Scotland in June, July and August of 1980. We just got a call from an agent here and an agent there and everything was like ten days, two weeks in the future. Nothing was mapped out. It was like a gig here, a gig there. No tour. Nothing. I think the most we ever got was a month of Sundays at the Marquee. That was about the longest we got into the future.

“When Bill could see, ‘Wait a minute we released this song Country Club and Party Fears Two in the summer of 1981 and now we’re in the summer of 1982 and you’re asking me to go out and play this all over America for the next eight months? He just went: ‘Fuck that. No.’

“That’s the rock ‘n’ roll machine, if you like. That’s what you have to do, that’s the way it works. You can’t get round the world unless you tour. That’s just what you have to do. And it just wasn’t in Bill’s make-up. It would have ground him down. He just would not have been able to take it. And he made that pretty plain. He didn’t turn up for rehearsals—and I’m not saying that as a down on Bill, he didn’t turn up because he couldn’t bear to turn up to rehearse these songs, to make them sound kind of like the record. His head was already going forward. And he probably wanted to work with other people because I’m good, okay, but Bill was really something special.”

“At first, I was angry. Bill said, ‘Let’s be a studio band then.’ I said, ‘No. You know this everything I’ve worked for with you for the last six years.’ When you’re so focussed on that thing for six years—going on for seven years really—and you’ve been so focussed on it since you were twelve in general but six years with the same person and suddenly that’s taken away from you—put it this way. Like that thing I said about I thought everyone found it easy to do this and do that—suddenly I realised people didn’t find it easy. And the thing I realised when I produced other people—I thought everyone could sing like Bill and do it in one take or two takes—how wrong I was when I was at take 46 with whoever was singing.”

“But I don’t think you could have changed it. Bill’s mind was made up. Even Bill would not have said that flippantly.”

Rankine quit The Associates. MacKenzie carried on. But the special magic that dovetailed this duo together was gone—and neither were to reach the same heights again.

It could have been all so very different.

“I went off the rails a bit—drank myself into oblivion for about four months. Then I came back and said, ‘Okay, I understand this—no problem.’”

Rankine signed a new record deal as a solo artist.

“I’m no singer. I can remember when I signed the contract with Virgin in the middle of ‘86 and I said ‘I bet I get the registered letter saying I’ve been dropped in seven months.’ I didn’t. I got it in five.”

Rankine continued producing bands like the Cocteau Twins, Paul Haig, and Tuxedomoon. With a family to support, he then started curating a music course at Stowe College in Glasgow where he signed and nurtured bands such as Belle and Sebastian, Snow Patrol and Biffy Clyro in the 1990s.

In 1992, a review in Q Magazine of MacKenzie’s new record was to bring the duo back together for one final hurrah.

“There is a review in Q Magazine of Bill’s latest album in August 1992. It was a guy called Martin Atkins, I think. At the very end he said, ‘Is it not about time to phone Alan Rankine?’”

Five days later he did.

“Apparently, Bill’s dad had read this review in Q and he had phoned up my dad to get my number in Edinburgh. Bill never knew this and my dad didn’t tell me about it till five years ago because he had promised Bill’s dad he wouldn’t tell until after he was dead. So the two Jims—my father Jim Rankine and Jim MacKenzie. I never knew about that until five years ago.”

“Bill phoned me up and said, ‘Do you want to do some stuff again?’ And I said, ‘Yes, no problem.’

“We got together in February of 1993. The first weekend we wrote eleven songs. It was just like I hadn’t seen Bill for two weeks.

‘Stephen You’re Still Really Something’ - The Associates 1993.

“He further explained to me the whole thing about touring he said, ‘Look, I’m a gay guy, I’m a bit of a gay icon—I’m not up there but I am what I am. I can fly to New York and play to four thousand gay guys and get paid ten thousand dollars in cash and fly out the next day. I can sing live to a DAT tape. I’ve got no roadies with flippin’ builders bottom. I’ve got no jeans with flippin’ keys on—all that rock ‘n’ roll nonsense. I can just go out and do my stuff and come back. Why would I need to tour? You know it’s a very much cleaner way of doing it.’

“And I totally get that. When we got together in February ‘93, I said, ‘Look man, let’s break the ice. You be David Bowie and I’ll be Mick Ronson and let’s do a song that’s in that vein.’ I just started riffing away. Out comes “Stephen You’re Still Really Something.” [The Associates response to The Smiths “William, It Was Really Nothing.”] You know, just a total piss-take. That was just a way of breaking the ice. From there we wrote “Edge of the World,” “International Loner,” and “Fear is My Bride.” They had a maturity about them.

“The Associates—Billy and I—had this thing that was bigger than us. It’s that kind of thing—it’s like invisible thread. It’s tangible. It’s like a thing called the God particle. All this stuff that’s around us is here but you can’t see it, but that’s what it is. It is kind of tangible.”

Billy MacKenzie died in 1997.

Rankine continues to write (“Anything that comes in my head”) and produce—most recently curating with bassist Michael Dempsey deluxe reissues of The Associates essential first three albums The Affectionate Punch, Fourth Drawer Down and Sulk which will include rare and unreleased material. (“There is quite a lot that we didn’t actually get released.”) He is currently planning a new reunion of the remaining members of The Associates for a one-off gig in London. If it proves successful—there may be more.

Before I leave, Alan plays me a track he wrote with Billy in 1977.

“It was done just at my piano in my parents’ front room that we never demoed, never recorded, never played live and we forgot about it. About six years ago I was co-writing songs with Steven Lindsay from the Big Dish and I said Steven I’ve got this song. Because it had never been recorded properly—I knew it was good because I remembered all the melody, all the lyrics, every inflexion of Bill’s delivery—it was still in my head. Steven ended up doing it. I got Craig Armstrong to do the piano because he’s the real deal on the piano—he’s got the jazz.”