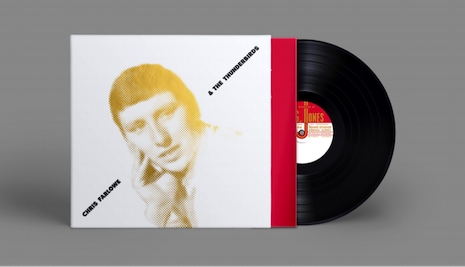

The cover of ‘The Beginning,’ courtesy of JimmyPage.com

One of the limbs of Osiris could turn up in your mailbox soon. On April 30, Jimmy Page will release the first recording he ever produced, at the age of 16: the 1961 demo of Chris Farlowe & the Thunderbirds, whom he judged “the best band in the south.”

It’s a document of London rock and roll as it existed before the Rolling Stones or the Yardbirds, and you can’t miss the qualities that would have recommended the group to teenage Jimmy Page: the voodoo rhythm section, the shit-hot guitarist, fronted by a conjuror, playing hard, spellbinding blues with restraint, dynamics, control. It’s essentially live; the only studio trickery I can make out, other than Page’s anachronistic decision to record the sounds the drummer was making, is a touch of reverb. As on Elvis’s Sun sessions, the musicians are surrounded by emptiness, as if they are recording in outer space, or Chicago.

Last week, Chris Farlowe graciously spoke to us about the album and the beginning of his career in music. Embedded at the bottom of this post is the premiere of “Let the Good Times Roll,” selected for Dangerous Minds by Jimmy Page.

Why has this taken so long to come out?

That’s a good point. I suppose because Jimmy has been so involved with the beginning of Led Zeppelin, of course, and whatever tours they had to do, and whatever recordings, and whatever they had to do, I suppose it just got bypassed. And it was only about a year ago, I was working with Van Morrison, and someone said, “Van’s got a private party tomorrow night for one of his records, are you coming?” And I said, “Yeah, I’ll come along, that’s fine.” So I walked in, and then Van said, “Your mate’s here.” I said, “Who?” He said, “Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page is over here.” I said, “Oh, great.”

So I walked over to Jim, and we said hello and greetings to each other and all that lark, and then I said to Jim, “Jim, what are we gonna do about that bleedin’ acetate that we had done 56 years ago?” And he said, “You’re right, we’ve gotta do something about it, because it’s an important record.” And I said, “Right, let’s do it.”

And then he got his act together and he did it!

Was this something you’d had a copy of all these years?

Yeah. I’ve got an acetate copy, Jim has an acetate copy as well, of course. But I couldn’t do nothing, because we were part owners of it, 50/50, so I had to get permission to do it from him if I wanted to do it on my own—but then again, Jim wouldn’t allow that anyway, because he wants to be involved with it, because he produced it when he was 16 years old.

And people say to me, “How come he was only 16 and he produced this album?” And I say, the man is a genius, I think, because he had the instinct and the foresight to realize that we were a great band, and I’m a good singer. He said, this guy deserves to be put down on record, and it took a 16-year-old boy to do that for me! Which is strange. I don’t think it’s happened ever since, really.

Was he still playing in skiffle bands when you met?

Yeah. I had a band—well, the Thunderbirds, of course, which you hear on that record—and we used to tour, do all the local clubs and the pubs and all that sort of stuff. And we did a place in Epsom called Ebbisham Hall, and Epsom is where Jimmy comes from. So, all of a sudden, look at the side of the stage, and there’s this young dude standing there, listening to my band. And when we come off, he said, “Hello, my name’s Jimmy Page, and I think your band’s fantastic. I like your guitarist, he’s really cool.”

I said, “Yeah, he’s good, isn’t he?” He said, “Cor, dear, he’s so smart, all in black like that—he’s really got a good image.” And he influenced Jimmy Page, you know, my early guitar player did.

Is that Bobby Taylor?

Yeah, Bobby Taylor, who now lives in Los Angeles, funny enough. He left my band and became a TV actor and a film actor, and now he’s got an acting school in LA.

So anyway, Jimmy said, “I love your guitarist,” and he’d keep turning up at gigs, and that’s why he got involved with the band, I suppose.

Was this the first lineup of the Thunderbirds?

Yes, first lineup ever. We had a double bass in the very first lineup, which was the same group of guys; when we were doing, like, rockabilly we had a double bass. And all of a sudden, we thought, Well, rockabilly ain’t gonna really last, you know? Rock and roll’s coming in, so I think we’d better go over to a normal bass guitar instead of a double bass. So the double bass player bought a normal bass, and that was it, really.

Who were your contemporaries? This was before the Rolling Stones had even formed.

Yeah, this was a year before the Beatles ever recorded a record, this was made. I was very lucky. I had a mother who was a pianist, and she used to play the piano in the pubs and the clubs during the war, in London, to all the soldiers. And I used to sit down beside her—four or five-year-old boy at the end of the war—and my mother would teach me Doris Day songs. “Secret Love.” I loved Doris Day, I thought she was fantastic, you know. I still love Doris Day. My very first influence was Doris Day, which is amazing, really.

And then, of course, rock and roll came in, and that was it, then. I went to see the film Blackboard Jungle with Glenn Ford and Vic Morrow as a young kid, and we weren’t allowed in, because it was an X certificate, an adult film. So I slipped in with my father’s overcoat and his hat, to make me look like I was 18 years old. [Laughter]

And, like, that still didn’t work, because when I walked in, the guy on the door would say, “Oi, how old are you?”

“I’m 18.”

“You don’t look 18.”

I said, “I am 18!” And they let me in. And then I saw Bill Haley in that film singing “Rock Around The Clock,” and I thought, Wow, man, that’s what I wanna do, I wanna be a singer. And that’s how it happened.

So where did your repertoire come from? Records?

Well, I was very lucky. I was born in London at the beginning of the war. My mother, of course, played the piano, and taught me about different singers. My mother was into jazz, and she said to me, “You wanna be a singer.”

I said, “Yeah.”

She said, “You have to learn, get some good singers under your skin here, like Doris Day.”

I said, “What else do you think I could do, Mom?”

And she said, “Well, go down the record shop, and I’ll buy you one record every week, an album.” And they were only, like, one pound something, 30p, I think, in those days. And she said, “Go down and listen.”

So I went into the record shop, and I said to the woman behind the counter, “I want to become a singer, and I want to learn from singers. Can you give me any singers, please?”

She said, “Have you ever heard of Sarah Vaughan?” and I said, “No.” She said, “Well, take this album in that booth over there and play the album, see what you think.” And of course, I heard the [first] two tracks that came out and said, “I’ll have that record, please.” Next week it would be an Ella Fitzgerald record. Next week after that it’d be an Anita O’Day album, or a Jeri Southern album. I was really into the women jazz singers, because there was a lot more of them than men, of course, and it made me wanna be—I used to like to scat sing, and copy Ella Fitzgerald’s scat singing, and all that sort of stuff. So that’s how I started really learning my craft, you know.

Photo courtesy of Chris Farlowe’s collection

What was it about the jazz singers?

Oh, I just liked their voices, and the way they were interpreting the songs. Doing the slide, and elongating the notes, and coming short on the—I used to love that, and I used to copy that, right to the tune, you know. My mum would play the piano, and I would sing—she’d go in a pub, and I’d say, “Could we do ‘Passing Strangers,’ Mom, like Billy Eckstine and Sarah Vaughan?” And she said, “Yeah, go on then!”

And of course, the people sitting there would think, Bloody hell, what is this little kid singing like that for? [Laughter] They’d say to my mom, “Is that your boy?” and she said, “Yeah.” “Where’d he get that voice from?” “I don’t know. He just started singing like that.” And that’s how I learned it, mainly, copying women jazz singers.

I liked Tony Bennett, I liked a little bit of Mel Tormé as well. I liked Johnny Ray as well, Johnny Ray was a good influence on me, because I used to impersonate him at the parties. My mom used to say to me, “Go on, take off Johnny Ray and show the people how you can do Johnny Ray,” and it was a storm, really.

Is this the first recording you have of yourself singing?

What, this album? Yeah. I did one—you probably had this in America, where you could go to the seaside when you were kids with your mom and dad, and they would have a booth on the sand, and you could go in there and record your voice. Well, I did that, and I sang—I don’t know what it is, a Doris Day song—but we’ve never found that record that they gave us afterwards. Never found it; it just got lost in the mire, you know. Someone’s probably got it. Probably worth a few shillings now, as well, if they found it. But the album is the first thing I ever recorded, and that was with Jimmy, yeah.

What are your memories of the session? Do you remember anything about the studio?

Yeah. I’ve got the boys; we couldn’t afford to go by taxi, because it was quite a way from my house, about 10 miles, so we carried all the equipment, and the drums, on the Tube.

Oh my God!

Yeah. Carried a full drum kit, the three of us, bass, guitar amplifiers, carried it all—we were bushed by the time we got to bloody Morden [laughs]. Of course we did—we couldn’t afford nothing like that; we could just about afford the bus. So that’s how we did, we carried it all on the Tube, and then took it all the way back home on the Tube, as well. I suppose we’re finally getting paid for it after 56 years. [Laughter]

Gives hope to young musicians, right?

Yeah, we get our Tube money back, and our bus money back, now.

And then when you got to the studio, did you just run through your live set?

Yeah, that’s basically it. Jimmy said, “I didn’t need any amplifiers. It’s gonna be plugged straight into this set. Induction.” We didn’t know what he meant then, but he did. He was really into all that recording lark, you know, even at that age. And then after we recorded, we went round his house, and he had a little recording studio in his house, with his mom and dad, I remember that.

But yeah, we just did our normal set. We recorded the whole album within about three or four hours, I suppose, which was nice. Now we take three or four days just to do one song sometimes, don’t we? Which is a pain.

It’s got the energy of a live set.

Yes it does. Yeah. Someone was talking to me the other day, and they said it sounds like voodoo, like Bo Diddley sort of stuff. And I said, “Yeah, it’s got a little Bo Diddley feel to it. Yeah, you’re right.” Of course, we liked Bo Diddley as well, when we were kids, you know, so he’s probably an influence as well on the guitar player. And the drummer, especially, the drummer’s great. He does some great stuff on that, and he was only 20 years old.

I wonder if that’s part of what drew Jimmy Page to you guys. Some of these performances are kind of spooky, like the performance of “Money.” You don’t rush it at all.

No. You know, Jim was talking about it the other day, and he said, “You’ve heard the Beatles’ version of ‘Money,’ haven’t you?” And I said, “Yeah.” And he says, “It’s pretty tame. Your version is—you listened to the original record, didn’t you?” I said, “Yeah, I did.” He said that the Beatles probably heard another band do it, and they copied that from the band, but he said if they’d have heard the original record by Barrett Strong, they’d have played it a little bit different.

Because me, I wanted it dead-on, I wanted to be an R&B singer, you know, that’s it. I mean, the Beatles are not R&B singers, that’s for sure, though they were great anyway. But I wanted to do what I wanted to do, and that’s how it came out.

I love hearing you sing the guitar solos along with Bobby Taylor.

Yeah! That’s when I was learning my scat singing. “Matchbox,” where I’m copying his solo. Yeah, that was good. Which I think is the same solo as Carl Perkins plays, as well. We were all copying our idols, you know, in those days, but it come out well. I’m known for that, scat singing and all that sort of lark. Even today, I put a little bit of scat singing into some of my songs.

You get singers come up to you and say, “How did you do that thingy-bob with your mouth?” I say, “I don’t know, I just did it.” It’s always been like that; I’ve never had any problem sort of copying different styles of music, you know? I joined Colosseum, who they call a jazz-rock band, after that, one of the great bands. A completely different type of music to what I’d ever [done before], but it was like falling off a log for me. Easy.

’Cause you had that jazz vocabulary?

Yeah, that’s what it is. I learned my craft in the very early days, so when Colosseum who are, like, jazz-rock come up to me… Dave Greenslade used to be my organist in the later Thunderbirds, when Albert Lee was my guitarist. John Hiseman said, “We’re a great band, but our singer’s too timid. We need someone with a lot of guts behind his singing.” And Dave said, “Why don’t you try my man Chris Farlowe?” And he said, “Alright, get him down for an audition.” So I went down to their rehearsal studios, I sang two numbers, and John asked me when could I join the band? That was it, really.

Photo courtesy of JimmyPage.com

So Chris, what can you tell me about this movie they’re making about you?

It’s been going on for about four years now, but they’ve followed me everywhere, this film crew—a great bunch of guys—and they’ve filmed me in America, filmed me everywhere in Europe, with Colosseum, with my band, with Van Morrison. And it’s all about my life, where I started, like you see with this record, and how it progressed. They’re interviewing a lot of artists, as well, like they’re interviewing Jimmy shortly, I believe, and then they’ve interviewed Van, Eric Burdon, Albert Lee, quite a few other people.

I run my business, as well, I sell modernist furniture and glass and all that sort of stuff, as well. Like Charles Eames and this sort of stuff. And that’s what I’ve been doing for 40-odd years, as well. So I’m into the modernism, furniture lark, as well.

I think it all revolves around the same thing, rock and roll, it’s that feel. Design of furniture. And then the sixties started, of course, and everything went to sixties design, all that fashion stuff, and then it went to punk after that, leathers and all that sort of gear. But I think it’s a continuation of rock and roll, that’s what it is, really.

Something about those postwar years.

Yeah. Certainly in England. I mean, when that Liverpool sound came along, we were the southern, we were the London sound. There was a lot of bands in our neck of the woods that were more blues-inclined than the Liverpool bands were, you know. Like Gerry and Pacemakers and the Merseybeats and all that, they’re more poppy. Us in London, we were more the blues, the R&B, because we were lucky enough to have these artists like John Lee Hooker and Howlin’ Wolf coming, who were completely unknown in England, and also completely unknown in America, as well. And they were brought over by Chris Barber, the orchestra trombone player. He had enough money to bring them over as guests for his orchestra, and of course they came over, and people loved it. That’s the first time they’ve ever seen black musicians like this, you know. So England’s got a lot of respect for doing things for things for that music genre, you know, from the Beatles downwards, or upwards, whatever you wanna call it.

Who were the other blues bands in London at that time? You’ve mentioned Eric Burdon and Van Morrison.

Eric Burdon and the Animals, you had Art Wood’s Combo, the Sheffields, Johnny Kidd & the Pirates, John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers with Jimmy Page and of course Eric Clapton, you had Brian Auger with Julie Driscoll. All playing this jazzy, bluesy stuff, you know, which was great. The Rolling Stones were based down our way, and they were more into the blues, as you know, their early records like “Little Red Rooster” and all that sort of stuff, which is great. They did a great job. I mean, I didn’t like much of their music a long time after that, you know; I liked their bluesy stuff. And you had, like, the Kinks. When the Kinks first started, they were really bluesy—they made some really good blues stuff, they did. That’s how it all started, really, in London.

It’s funny, I grew up hearing you sing [the Jagger/Richards composition] “Out of Time” on the radio, and I must have heard it a hundred times before I realized that it had anything to do with the Rolling Stones. It just sounded like a classic soul song.

Yeah, it’s Northern Soul. I used to be a Mod in those days—you know what Mods are like, wearing winklepicker shoes, and Sta-Prest trousers, like Stevie Marriott from the Small Faces, that sort of look, you know. That’s how we started. And then when, of course, we got into Colosseum, we got long, shoulder-length hair, which was a complete difference. It freaked my dad out very, very much when that happened. [Laughs]

When you came home with long hair?

Yeah, oh yeah. ‘Cause my dad was a soldier during the Second World War, in Normandy, you know, and he was a military policeman, as well, to top that all off. So when you walked in and you had long hair, he would look at you and think, When are you gonna get your hair cut? I said, “I’m not gonna get me hair cut! I’m a singer now.” But he didn’t like that at all. My mother was completely different, she was all for me being a singer. My father would never… in all my life, my dad never came to one of my concerts, you know. So that just shows you… He’d go to the racehorses, he liked to see the racehorses, but not his own son in music. [Laughs]

Your mother was the musical one.

Oh, she was the one. She was fantastic. If I wanted to be a singer, she said, “John”—my real name’s John—“if you want to be a singer, don’t notice of what anyone else says to you. If they say ‘You’re joking, what do you want to be a singer for?’ you just do it.” And I did it. I did all the clubs. We did our apprenticeship for about seven or eight years, playing nearly every night all over the place, you know, and that’s what I feel doesn’t help people today, you know, when you get, like The X Factor and all that, these young people who have never really worked hard at their profession, and yet they get a break on the TV which we didn’t know about until we became number-one record people; nobody wanted to know us in those days. There wasn’t any basic shows anyway for people to sing on, not like today. But the poor youngsters of today, you know, they get voted in and win The X Factor, and then a year later, they’re forgotten.

I’ve read that the Doors used to play six nights a week, two sets a night. I think that’s an opportunity that doesn’t exist for young musicians these days.

I’ve got my original diaries from the ‘64s and ‘63s, all that lark, and some weeks I’m doing 13 gigs a week. ‘Cause the Flamingo Club was open in the evening, and then it went to the all-nighter—that was six o’clock in the morning—and then they had an early one on Sunday morning, as well, so you got a few hours, and then they had to have an afternoon session, and then in the evening we would go to a university or something and play a gig there. [Laughs] So we’d do about five gigs a day.

That’s incredible.

Well, we’ve gone all through that, and we’ve had our apprenticeship, which was great. There’s nothing better than being an apprentice, you know.

Well, if you were an apprentice, did you have teachers?

Never been taught, never in my life, no. Learned it all through me and my mum. No singing lessons, nothing. I just naturally sang, just like that. Even when I was three or four years old, my mum used to hear me in my bedroom, put in the cot, and she said “You’d be just making noises!” Truly strange, she said, but there you are.

You’re a born singer.

Yeah, born natural voice. I don’t have any problems with my voice, ever. I’ve never smoked a cigarette in my life, either, so that’s probably helped a lot.

Chris, thank you so much. It’s been a pleasure talking to you. Is there anything else you wanted to say about the record?

It’s a great record and it’s out there now, or will be at the end of the month. Jimmy’s doing a lot of work for it as well, it’s one of his big things that he wants to do and make a success of. It’s doing very well in presales, I believe, doing very well at that. I look forward to—perhaps something will come of it where we can go back on the road again and do some music with Jimmy Page. That would be nice.

That would be terrific!

That would be lovely, yeah. I’ll have to have a word with him over a cuppa tea. [Chuckles]

Chris Farlowe & the Thunderbirds’ The Beginning…, to be released April 30, is available for preorder from JimmyPage.com in standard and deluxe editions. The standard edition will also be available through Amazon. Below, Chris Farlowe & the Thunderbirds play “Let the Good Times Roll” in 1961.