David Sherwin was eighteen years old when he co-wrote a script about two schoolboys (Mick Travis and Johnny Knightly) returning from the freedom of the summer holidays to endure the horror and torture inflicted in them by their public school teachers and elders—floggings, beatings, buggery. The story concluded with Travis being expelled for having a relationship with one of the younger pupils. Called Crusaders Sherwin and his writing partner John Howlett, touted the screenplay around different agencies where it was considered promising, but more suitable as material for a documentary than a feature film. Sherwin disagreed and kept faith with the adventures of Mick & co.

Eventually he met with director Lindsay Anderson, who encouraged Sherwin and Howlett to turn Crusaders into something far more extraordinary. Sometimes however this encouragement was often to dismiss the script as “drivel” and “rubbish,” but Anderson believed the screenplay had great ambition and merit and offered something more intelligent to the kind of movies being made at the time.

A chance meeting with Albert Finney brought on board actor Michael Medwin as producer. Medwin was best known as a character actor with a long list of films and hit TV series to his name. He was then producing Finney’s movie Charlie Bubbles. The partnership of Anderson and Medwin made it easier to win financial backing from Paramount Pictures—who had little idea what sort of film they had commissioned.

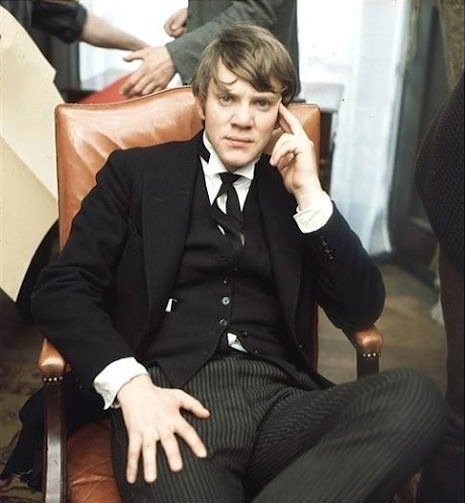

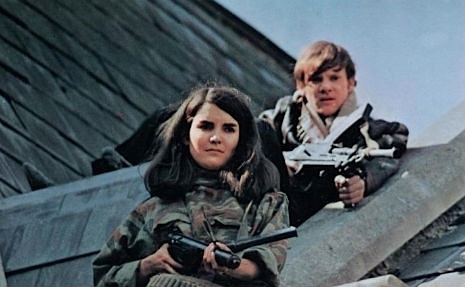

The casting was painstaking and according to Sherwin Malcolm McDowell improvised “the best audition in the world” with a scene with actress Christine Noonan set in a cafeteria. McDowell was an unknown and hadn’t learnt his lines. It didn’t matter as McDowell and Noonan were soon rolling around the floor of the rehearsal room behaving like wild animals. This scene was later recreated in the film.

Filming started in January 1968 with a “terrified” Anderson uncertain where he would point the camera. It was just first night nerves as Anderson held everything together delivering the complete film in November of that year, as Sherwin recorded in his diary:

Lindsay has completed his final cut of If… Paramount are so shocked by what they think is madness that they try to sell it to an American art-house chain. The art-house chain think it is madness too. If… will never be shown.

He shouldn’t have worried as If… opened in London on December 19th 1968. Most critics were harsh, disgusted and horrified by the film and by Anderson’s reputation as a Marxist. This was 1968, the year of the Paris riots, Vietnam, Mao’s cultural revolution and social unrest across Europe. The film was seen as a threat against the values of the establishment, and as promoting violent and bloody revolution.

In an interview in 2012, McDowell explained some of the background to these fears:

“After the Second World War in England, the establishment thought they could just carry on like they did before the war. Young people were fed up. So, slowly, they started to rebel. There was not a revolution in streets like there was in Paris. It started in its own way; it started in 1956 with the play Look Back in Anger – which was a beautifully written and violently anti-establishment play. Its main character was very compassionate, very robust, very intelligent. It sent shockwaves which spread everywhere [and influenced] painting, poetry, music,” McDowell told me in explaining the social context of Lindsay Anderson’s film.

“It showed the schools that have been there for a thousand years – and they were incredible schools. In Britain, aristocrats sent their children there to educate them, to send them out to rule the empire. And so the revolution takes place in one of these schools. That sent shockwaves. In England – oh, God! – it was like heresy. And If… was the end result of this period.”

In a question-and-answer interview written by Anderson in 1968, the director gave his own view about the meaning and significance of the film:

The work is not a propagandist one. It does not preach. It never makes any kind of explicit case. It gives you a situation and shows what happens in this particular instance when certain forces on one side are set against certain forces on the other, without any mutual understanding. The aim of the picture is not to incite but to help people to understand the resulting conflict….

It is about responsibility against irresponsibility, and consequently well within a strong puritan tradition. Its hero, Mick, is a hero in the good honorable, old-fashioned sense of the word. He is someone who arrives at his own beliefs and stands up for those beliefs, if necessarily against the world. The film is, I think, deeply anarchistic. People persistently misunderstand the term anarchistic, and think it just means wildly chucking bombs about, but anarchy is a social and political philosophy which puts the highest possible value on responsibility. The notion of someone who wants to change the world is not the notion of an irresponsible person.

The critics may have sniffed but the public loved it, and If… went onto win the Palme D’Or for Best Film at Cannes in 1969.

Cast and Crew brings together the key individuals involved in the making of If…: producer Michael Medwin, writer David Sherwin, assistant director Stephen Frears, cameraman Miroslaw Ondricek, editor David Gladwell, along with archive footage of Lindsay Anderson. The format of the show (guests interviewed in a studio) is a wee bit cosy, especially for such a revolutionary film, however, there is plenty of fascinating insight into the making of this classic movie.