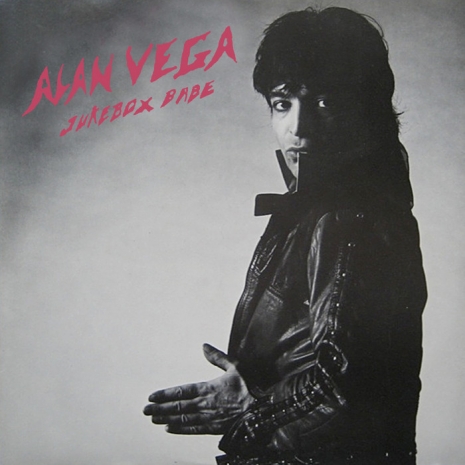

The author and one of his biggest heros

A guest post from D Generation’s Jesse Malin on Alan Vega

I first heard Suicide on a cassette tape I came across at the False Prophets’ studio on Avenue B, a cool old thrift store turned punk rock rehearsal spot and teenage crash pad. It was live tape that I believe belonged to the Prophets’ bass player, Steve Wishnia. It was on a label called ROIR that only put out cassettes, if can you imagine that, but they had a very cool thing going on, like the first Bad Brains LP, Johnny Thunders’ Stations of the Cross and the infamous New York Thrash tape.

The name Suicide always intrigued me but the raw electronic minimalism went way over my teenage hardcore head. Where were the guitars? Where were the drums? At that age, I needed things to be a certain way. Looking back, I guess I wasn’t ready for it. Truthfully, it kinda scared me a bit. Then I saw a copy of the New York Rocker with a cover shot of Alan Vega and Johnny Thunders looking cool and dangerous, hanging out on the floor, smoking and drinking in some downtown loft. Alan looked like Johnny’s more together older brother, but still badass as fuck. That photo spread would revisit my mind in the mid 1980s when I was looking for something outside of the hardcore scene to stimulate me again as a listener and as a musician. The scene I was in was becoming way too macho—and way too metal—for me.

The conformity level had risen to such heights that it was contradicting everything we originally stood for… so I began listening to Billy Bragg, The Replacements, Graham Parker & The Rumor, and many other troubadours fueled by anger and song. I saw the Bob Dylan film Don’t Look Back at midnight at the St. Marks Cinema and began to see that my precious punk rock had existed way before and worked on many levels… not just “Loud Fast Rules” (Hey, I was still in my teens).

One day I came upon a copy of Bruce Springsteen’s Nebraska, and, even though I always had mad respect for him as an artist and live performer, I was not a real fan until I sat down with Nebraska by myself and read along with the lyric sheet. It felt like it was the middle of the night and he was sitting there right with me telling these hauntingly honest stories with dead-eyed conviction. How could this this huge rock star be so connected to the human struggle and the working class on such a street level while still giving us a glimmer of hope?

By this time, Born in the USA was out and I got a lot of shit from my punk rock friends thinking that it was all some patriotic, macho Rambo crap. I had to argue to get them to read the lyrics where, in almost half the songs on album, the main characters all ended up in jail. So I was a new fan, and so was most of the world in that summer of 1985. Hopefully some of the masses got the message through the FM dial: Use the system to fuck the system, or as least hold up the mirror up to it…like Dylan, the Beatles and the Clash had also done.

As a kid I always wanted to know all the crazy backstories about the records and artists I liked. I read tons of music mags, trying to get all the info I could. One day I came across an interview where Springsteen talked about Suicide and how their first record, especially a song “Frankie Teardrop,” influenced Nebraska in a big way (check out the screams on “State Trooper”).

I had recently broken up my first band Heart Attack and formed a group called HOPE. We were playing at a place called the Cat Club one night when an old school record guy named Marty Thau approached us. He said he was interested in taking us into the studio to record a record, and that he had worked with the the Ramones, NY Dolls, and was currently working with Suicide. Next thing we know, we had a gig opening for Suicide at a jam packed sold out CBGBs on a boiling August night. We played our songwriter-esque rock set and went out into the crowd to watch Suicide. It was the loudest, most intense thing I had ever seen (and I had been to a few Motorhead shows).

Suddenly the CBGBs that we were so familiar with became a very different place that night. Alan was screaming like he was going to have a breakdown. It was scary as anything and full of anger, but yet there was something very romantic and classic about it, in a 1950s way, while still sounding like it was from another planet. The levels got louder and louder and pulse was so intense, made by only two people (Alan and his counterpart Martin Rev), without even trying.

Then, all at once, it ended abruptly with Alan smashing the microphone several times into his face and then slamming it down on to the floor. After the show, Alan collapsed down on a broken wooden bench behind a sheet in our dressing room, sweating and breathing like he just came out of a heavyweight brawl, but dressed like an Elvis apparition passing through the Bowery. He didn’t say a word, just slowly nodded his head at us kids.

About a year or two later, my friends and I find ourselves out every Sunday night at a New York City nightclub in a big old church called Limelight. It was the height of the hair band days and, even though we hated 99.9% of the music, we went there to chase the girls (which there plenty of). Sometimes, feeling a bit self-conscious about how lame we were hanging out in this scene, we would hide in the dark sidelines and drink up the courage to yack to as many big-haired, sleazed-up ladies as we could.

One of those spots in the shadows was the small balcony bar with very few people, but standing there we noticed Alan Vega and a friend. My buddy John Carco and I started talking to him, and he was super friendly, very New York and down to earth. He actually wanted to have a real conversation, which was surreal in this debauched rock hellhole. He was soft-spoken and sweet, but we didn’t want to bother him so we walked off rather quickly.

On Sundays to come, we would see him there in the same spot with his same friend, smoking and drinking in the corner. He would wave us over, buy us a beer and tell us all his thoughts on the world (politics, music, New York, whatever). It was always interesting, unique and felt familiar- like regular guy at the bar. It gave our sleazebag Sundays a bit of substance and meaning.

A short while later, Suicide would play the Limelight, and now I was completely ready take it all in and enjoy it for all it was. Ric Ocasek came out and joined them. I remember reading about how Suicide opened for The Cars and other groups while getting hits with chains, bottles etc., but always finished the show. Every time that I’ve had the misfortune of having things thrown at me (bottles, chains, or whatever), I think of Alan and Marty, and it would always give me the strength to hang on.

Five years later I’m in the studio with D Generation and we are recording an album produced by Ric Ocasek. One day I asked him about Suicide and he offered to bring Alan by the studio. Next thing you know, Alan Vega is sitting on the couch at Electric Lady Studios while, funny enough, were recording our new song “Frankie.” We asked him if he would like to sing on it and he asked us what was it about. I told him some of the lyrics and he asked the engineer to take out all of the guitars and only leave the bass, the kick drum, and my voice. He then went in the booth and began to free form along to the track. It was so cool watching him work. He added a great juxtaposition, challenged our performance and fucked with it in the best way.

After that, I would never miss a Suicide gig again if I was in New York City. As the new millennium rolled in, there seemed to be more respect and accolades for Alan and Marty and what they had done with trips to Russia and honorary award dinners, but they were still way ahead and world was still trying to catch up.

Following the release of my first solo LP, I had the great honor and luck of getting to play some shows, and even some of my own songs, with Bruce Springsteen. He was very open and super supportive. After the shows we stayed in touch a bit while I was making my second record, The Heat. Just after its release, Bruce was out on a solo tour and I heard he was playing a version of Suicide’s “Dream Baby Dream,” so I called up Alan to see if he wanted to go to Connecticut to check it out. He said yes, and me, Danny Sage, and Bob Benjamin picked him up downtown and we all drove to Bridgeport.

We got there just after soundcheck and were immediately escorted back to Bruce’s dressing room. We all sat on his couch and caught up for a while. Watching this was unreal – two heroes, two rock gods, two dads talking about their worlds. I remember Bruce giving Alan one of the greatest compliments, saying “if Elvis was born again he’d be Alan Vega.”

Bruce began preparing for his show and we went out to our seats, where one of Alan’s solo records was playing through the arena as part of the band’s pre-show walk-in music. It was a very moving and intimate show, especially considering that it was in such a large venue. Bruce closed out the show with an extended and super powerful “Dream Baby Dream.” Alan was blown away and really touched. It was an unforgettable night.

I hadn’t seen Alan in a few years, but I reached out to see if he would have any interest in performing at a benefit we were putting together for the kids of a special fan of mine who had taken her own life. Alan generously agreed to play at the “Benefit for Lucinda’s Kids” at the Bowery Electric.

A couple years later I got a call that Bruce Springsteen wanted Alan’s number and wanted to ask him something. I emailed his wife / manager, Liz, to get the new telephone number. She said that Alan would love to hear from him, but to let Bruce know that he had recently had a stroke and might sound a bit different on the phone. I never found out exactly what that call was about, but shortly after that, Bruce’s version of “Dream Baby Dream” was included on the new Springsteen studio album, High Hopes.

Alan, being the bravest of the brave, continued playing shows after his stroke. The last time I saw Suicide was a year and half ago, playing to a packed out room (mostly kids in their 20s) at Webster Hall. We went back to say hi after the show and Alan was in great spirits. His son, Dante, was by his side, and he seemed very at peace. We took a couple of photos, not knowing that that would be the last time we would see each other.

Walking through the gateway at the airport, on the way home from my last UK tour, me and my guitar player, Derek Cruz, began talking about the magic of Suicide and Alan, and maybe doing something with him again. When I returned home that night I received a message that Alan was gone. A few more came in that night and the next day. It hurt big time. I thought of his son Dante, his wife, Liz, his partner in crime Marty and the whole word that needed someone like Alan on the planet.

A few days later, while walking on E. 6th St., I saw Alan’s name in BIG spray paint letters. It made me really happy. D Generation played Irving Plaza a week later and we opened the show blasting out “Frankie Teardrop” while we walked onto the stage. As we closed our first show in many years, I held the microphone tightly, looked deep into the crowd and dedicated our last song, “Frankie,” to Alan.

D Generation‘s new album Nothing Is Anywhere reunites the classic lineup of Jesse Malin, Danny Sage, Richard Bacchus, Michael Wildwood and Dangerous Mind’s own Howie Pyro. They’re currently on tour in a city near you.