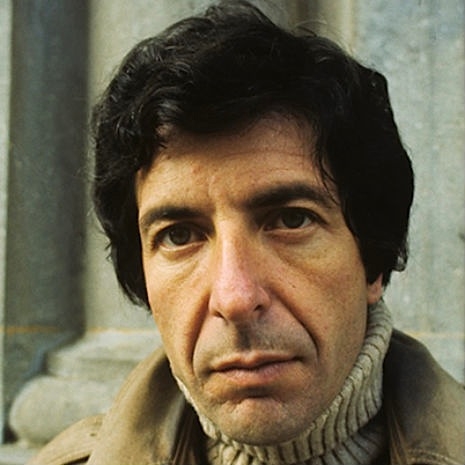

Our scene opens on the teenage Leonard Cohen attempting to hypnotize the family maid. Here’s Cohen, growing tall and lanky, losing the puppy fat, smiling, precocious, inquisitive, intense, with a zest for life.

Cohen has bought and studied 25 Lessons in Hypnotism How to Become an Expert Operator, a book that promises much—mind reading, animal magnetism and clairvoyant hypnosis—which the youngster hopes will deliver. As Sylvie Simmons explains in her biography on the singer I’m Your Man, the enthusiastic and earnest Cohen worked hard to master these powerful arts, and soon discovered he was a natural mesmerist.

Finding instant success with domestic animals, he moved on to the domestic staff, recruiting as his first human subject the family maid. At his direction, the young woman sat on the chesterfield sofa. Leonard drew a chair alongside and, as the book instructed, told her in a slow gentle voice to relax her muscles and look into his eyes. Picking up a pencil, he moved it slowly back and forth, and succeeded in putting her into a trance. Disregarding (or depending on one’s interpretation, following) the author’s directive that his teachings [on hypnotism] should be used only for educational purposes, Leonard instructed the maid to undress.

Simmons goes on to describe how Cohen must have felt at this “successful fusion of arcane wisdom and sexual longing.”

To sit beside a naked woman, in his own home, convinced that he made this happen, simply by talent, study, mastery of an art and imposition of his will. When he found it difficult to awaken her, Leonard started to panic.

Let’s freeze the frame on this “young man’s fantasy,” as there’s something not quite right, as neither Simmons or the young Cohen, appear to have considered the possibility that the maid was only feigning her trance, and had willingly taken off her clothes. This would turn everything on its head.

Cohen will later fictionalize the incident in his novel The Favorite Game, where the maid is also a ukulele player (the instrument Cohen first taught himself to play before the guitar), which his alter ego mistakes for a lute, and the maid for an angel. As Simmons puts it “naked angels possess portals to the divine.”

Simmons suggests this slim book on hypnotism had a greater affect on Leonard Cohen than just convincing the maid to take-off her clothes. The book was possibly a primer for Cohen:

Chapter 2 of the hypnotism manual might have been written as career advice to the singer and performer Leonard would become. It cautioned against any appearance of levity and instructed, ‘Your features should be set, firm and stern. Be quiet in all your actions. Let your voice grow lower, lower, till just above a whisper. Pause a moment or two. You will if you try to hurry.’

Scientific research has pointed out that some women are attracted to men with deep, low voices. While a touch of “breathiness” suggests a “lower level of aggression.”

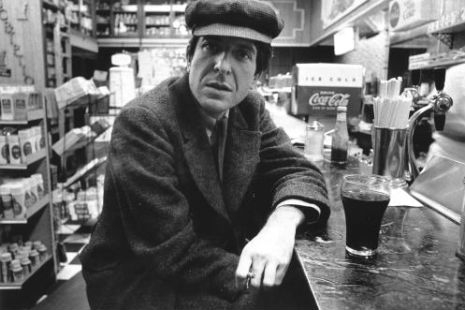

Cohen’s voice is instantly recognizable. He is aware of its power to mesmerize an audience: when he played at Napa State mental hospital in 1970, he jumped down from the stage and sang amongst the inmates, where anyone who could move “followed him around the room and back and forward and over the stage.” At the Isle of Wight concert, he was the only act not to have bottles thrown at him. Kris Kristofferson was booed off during his set, while a flare was thrown onto the stage during Jimi Hendrix’s performance, setting it on fire. Cohen was unfazed by such antics, he was mellowed out on Mandrax, and before he began:

...Leonard sang to the hundreds of thousands of people he could not see as if they were sitting together in a small, dark room. He told them—slowly, calmly—a story that sounded like a parable, worked like hypnotism, and at the same time tested the temperature of the crowd. He described how his father would take him to the circus as a child. Leonard didn’t like circuses much, but he enjoyed it when a man stood up and asked everyone to light a match so they could locate each other. “Can I ask each of you to light a match,” said Cohen, “so I can see where you all are?” There were a few at the beginning, but as the show went on he could see flames flickering through the misty rain.

As Simmons recounts the episode, Cohen “mesmerized” the audience, with just the power of his voice. Or, as Cohen described his talent himself in “Tower Of Song”:

I was born like this

I had no choice

I was born with the gift

of a golden voice.

Sylvie Simmons was a little girl who loved The Beatles, when she first heard Leonard Cohen sing. He was one of several artists, along with Bob Dylan, Simon and Garfunkel, Moby Grape and Spiirt, included on the compilation album, The Rock Machine Turns You On.

Sylvie Simmons: I heard him sing “Sisters of Mercy” and it just picked me up and throttled me. I loved his music and I bought all of his albums, until I became a Rock journalist in 1977, when I started getting them for free.

I interviewed him over time and found him fascinating and mysterious, and he was never quite captured in the books I read on him, so, I just thought I’d give it a go.

Simmons has produced an excellent, near-definitive biography on the singer, which reads like a page-turner, in-as-much as Cohen’s life has been filled with incident, adventure and romance, and like all heroes in such tales he comes across as likable and ever-charming.

Sylvie Simmons: Leonard is very charming. Every journalist who’s interviewed him in person, male and female, comes out with a little blush in their cheeks, smoking an imaginary cigarette. He is a total charmer. He is the kind of man who stands-up when you come into a room. He gives you a chair to sit down on, he makes sure you’re comfortable. All of these things

He’s not a Rock Star celebrity person. He has that kind of old world manners. He is a real gentleman. But mostly he has this very clever way of focussing on whoever is in the room, so in a way takes the pressure off of him—you’re so charmed you forget to ask any leading sort of questions or realize you’ve had the wool pulled over your eyes when he’s answered something. But I also think it’s just innate to him.

When Sylvie Simmons was given the blessing to write Cohen’s biography, the singer only had two stipulations: the book must not be hagiography, and the biographer must not starve to death. Everything else was fair game.

Sylvie Simmons: He just trusted me to do a diligent job. I wanted to write a biography on him with diligence and heart, that had some of his voice going through it, as I felt I hadn’t found that in other books.

Simmons spent three years immersed in Cohen’s life, working on the biography right-up to its publication. It took over her life to such an extent that Simmons was able to second guess how Cohen would respond to the various events in he encountered.

Sylvie Simmons: It was more a sense of understanding, like almost imagining as I was writing the book I was thinking: “Of course this would happen. Of course this would go on.” It was almost like I would anticipate what was going to happen next and it happened. Everything started making sense in that way it only can if you’re almost on the inside of the story rather than on the outside.”

Journalist, author and ukulele player, Sylvie Simmons was born in Islington, London, from where she ran away as soon as she could to Los Angeles, and started her career as a music journalist in 1977, writing for virtually every known rock magazine and music paper.

Sylvie Simmons: I was in music journalism when we were treated like the Rimbauds we thought we were, who jumped on planes at the drop of a hat, having endless champagne and free clothes. I’m glad I had that kind of experience because now publishing and music are two industries that have just died on their feet and have become almost like the Wild West—who knows when the shooting is going to stop and whether anyone will survive it?

From rock journalism Simmons went on to writing best-selling books on Serge Gainsbourg (’A Fistful of Gitanes’), Neil Young (’Reflections in Broken Glass’), Johnny Cash (’Unearthed’), as well as short stories and a novel (’Too Weird for Ziggy’).

I knew nothing about this great singer, poet, novelist, and musician before reading Simmons’ biography on I’m Your Man: The Life of Leonard Cohen. My knowledge was little more than second-hand footnotes from jokes by Alternative Comedians (Alexei Sayle), who facetiously lumped him in with feng shui, middle-class twenty-somethings, suicide, Sweden, IKEA, and depression. Cohen wasn’t someone I would sit and listen to by choice, not when I had The Bonzo Dog Band, Lou Reed, Sparks, and David Bowie. My loss, of course.

Simmons loves Cohen, and her passion for her subject has produced a thrilling, enjoyable and utterly fascinating book.

Simmons tells Cohen’s life from birth (21st September 1934, in Montreal, Quebec); through his privileged upbringing in a respected and well-to-do family (his father owned a successful clothing store); to his father’s early death (which left Cohen to be raised in a household of women); to the people, events and influences that have made Cohen one of the greatest singer-songwriter poets of the last half-century.

Simmons approach to such a mammoth undertaking was part detective, and part complete immersion in Cohen’s life.

Sylvie Simmons: It seemed to me when I started the book I better start my research in Montreal because that’s where he started his life. I thought I better go in winter because I want to feel exactly how hideous and ghastly it is to be in Montreal-winter, because that’s what he had for most of his life.

[Cohen] breezed through the early years of childhood, doing all that was required—clean hands, good manners, getting dressed for dinner, good school reports, making the hockey team, keeping his shoes polished and lined up tidily under his bed at night—without showing any worrying signs of sainthood or genius. Nor of melancholy.

Sylvie Simmons: Everywhere I went, something else would come up, “Oh no, I’ve got to the Chelsea Hotel,” or “I’ve got to go here,” or “I’ve got to go there.” It was a wonderful part of it, and I think it was very essential. It gave the people I was speaking to a kind of element of trust that I was willing to go to them and track them down, and speak to them that way, rather than just do it on the phone.

On the phone is how I interviewed Simmons. Her voice is young, infectious, bright, London, with no California. The problem with phone interviews—with no face to respond to—they lose out on the look, the gesture, the smile or shrug, that can often give meaning and color to what is being said.

Reading your biography, it struck me that Cohen has always been on the move, going off in search of something, is all this movement part of his creative process?

Sylvie Simmons: I think what it’s more about is that he came out of the egg as a very restless man, it was one of the things that he was cursed with rather than blessed with, and he certainly was blessed with a lot of things. He was blessed with a huge talent, and a supportive family, and coming from a very good background and everything. There were so many things he had going, but he had this restlessness and that related to so many things. He was always leaving somewhere, the first songs on the first album, like “The Stranger’s Song”—he was always the stranger running-off: when he got the grant to go to England, he moved to Greece, when he was in Greece he moved to Montreal, it went on-and-on.

He has this restlessness, and I think that goes right through his life. He changes geography a lot, he changes his spiritual path a lot, although he is consistently Jewish through the whole thing, and he insists on being called a Jew. And he has also been restless around women. I think he needs to live in this state of (almost) longing and yearning and emptiness. It is not much an excitement as this feeling of having to fill himself with something that goes deep in him. He is a very deep man.

Is this restlessness expressed in his songs?

Sylvie Simmons: I managed to get hold of the Artist’s Cards from Columbia Studios. There was a song that was on there called “Come On Marianne,” and it kept being called “Come On Marianne,” and about half-way through the recording process it became “So Long Marianne.” I thought it could have been a spelling mistake, so I called up Mary-Anne Ilhen, who is the Mary-Anne of the song, with whom Leonard had lived on-and-off for seven years, mostly on the island Hydra. I asked her and she said, with a kind of sob in her voice, “I always thought it was ‘Come On Marianne, Let’s keep this ship afloat,’ but I guess in the end we couldn’t.”

Leonard said that some writers had a kind of valedictory way about them, and I think that’s it. His things is, “Hey, that’s not a good way to say goodbye,” it was a goodbye put in the position of emptiness, which he was always looking for, so he could long for something to fill it.

If you could give three examples, what would you say were the three key moments of Leonard’s life?

Sylvie Simmons: This is so journalistic, why should it only be three?

I’m duly chastened, but I persist.

Sylvie Simmons: I should say that with a caveat because he’s had a very long life and he’s probably got at least nine of those moments. He’s had various different religious epiphanies and he’s also had careers as a writer and a musician. But I would say some of the key moments are:

The day that his father died, Leonard was nine years old and he buried his first piece of creative writing, he folded it into a minute, little knot, and put it inside one of his Dad’s bow-tie’s, and buried it in the garden, making a rite of his writing. He really does have this kind of ritual feeling towards his work.

Simmons adds in her book:

Leonard has since described this [piece of writing] as the first thing he ever wrote. He has also said he has no recollection of what it was and that he had been “digging in the garden for years, looking for it. Maybe that’s all I’m doing, looking for the note.”

Sylvie Simmons: That also led to the fact he was brought-up in a house of women, by his doting mother and sisters, so he was given much more freedom. The death of his father was a very, very key moment, even though Leonard himself as said it didn’t really have much impact on him, but I believe it did.

Leonard did not cry at the death of his father; he wept more when his dog Tinkie died a few years later.

The ‘Big Bang’ moment for Cohen (‘the moment when poetry, music, sex and spiritual longing collided and fused together in him for the first time’) came when he fifteen years old, when he chanced upon a book of poetry by the Spanish Civil War poet, Frederico Garcia Lorca, in a bookshop in Montreal.

Sylvie Simmons: As Leonard read it, he said that the hairs stood-up on his arm like hearing the music from the synagogue. There was almost this kind of synesthesia reaction to reading poetry that moved him in that way. Lorca was a musicologist, a collector of Folk Music, and he loved Spanish guitar, so, that got Leonard into buying a Spanish guitar and learning to play it. So, these two are very key moments

Another one, but quite a long way down-the-line in the 1990s, would be when he had been studying Buddhism and living at the Buddhist Monastery on Mount Baldy for five years, where he was ordained a priest. I had no idea how awful the Mount Baldy Monastery was until I went and stayed there. I actually emailed Leonard and said, “I’ve been here two days and I’m stealing a spoon and digging an escape tunnel. How did you last five years? You’re a greater man than I.”

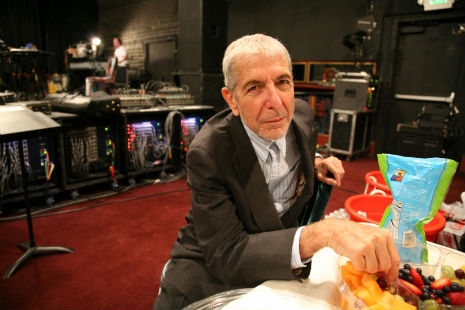

A fourth, would be the betrayal by his former manager [Kelley Lynch], who to some degree or another managed to wipe out all of his money, and he had to go back on the road, where he learned to love touring.

The tour not only restored Leonard’s funds, it improved on them considerably. But it also brought Leonard something more important: vindication as an artist….

All the heavy labor, the crawling across carpets, the highs, the depths he had plummeted, and all the women and deities, loving and wrathful, he had examined and worshipped, loved and abandoned, but never really lost, had been in the service of his. And here he was, seventy-six years old, still ship-shape, still sharp at the edges, a working man, ladies’ man, wise old monk, showman and trouper, once again offering up himself and his songs:

Here I stand, I’m your man.

What have you learned from writing the biography?

Sylvie Simmons: Persistence, probably, was the main thing, because obviously in the beginning some people, especially the women, were a bit reluctant to speak, because this is so personal. But they came to realize I was not after them for details of what went on behind the bedroom door—though a few of them actually offered to tell me. I wanted to speak to them because nobody had bothered to speak to these women and women are so important to his life, and they had an awful lot of insights to give me. So, persistence is one thing I learned.

Also, I think what I learned was that so many Rock biographies they are like in the beginning they have this huge rush and this brilliant life, and it all goes downhill, then they die, in the kind of way the best Rock stories are tragedies. But this one was almost like a story of redemption, keep the faith and it will come true. He got the kind of attention he wasn’t getting in the U.S. and Canada, at the end of his life, he got this amazing tsunami of love coming at him, and it continues, and he loves it, he’s learned to love the road. .

Otherwise, the usual things a biographer who gets into something deeply will learn, everything from the sublime to the ridiculous. Things like, finding out he was a ukulele-player before he was a guitar-player delighted me, because I’m a ukulele-player, an obsessive uke-player. There is something strange about uke-players, as they say, “One is too many and one-hundred is not enough.”

I got Leonard to out himself as a ukulele-player, and he was very keenly talking about meeting Roy Smeck, The Wizard of the Strings, when he was 10 years old and getting his instructions from a manual and teaching himself to play the uke, much as he taught himself to hypnotize and getting the maid to take her kit off. He is a very good student is our Leonard.

’I’m Your Man: The Life of Leonard Cohen’ by Sylvie Simmons is a available in paperback and Kindle.