Author John Cheever made a fleeting appearance in the film adaptation of his story The Swimmer during the summer of 1966. He played John Estabrook, a party guest at one of the homes Burt Lancaster’s character Ned Merrill visited on his journey to swim pool to pool across the county. In a letter to a friend, Cheever described his day’s filming:

What I was supposed to do was to shake hands with Lancaster and say “You’ve got a great tan there, Neddy.” Things like that. I was supposed to improvise…

So we rehearsed about a dozen times and then we got ready for the first take but when this dish [actress Janet Landgard] came on instead of shaking hands with her I gave her a big kiss. So then when the take was over Lancaster began to shout: “That son of a bitch is padding his part” and I said I was supposed to improvise and [director] Frank [Perry] said it was all right. I asked the girl if she minded being kissed and she said no, she said I had more spark than anybody else on the set…

Lancaster heard her. Anyhow on the second take I bussed her but when I reached out to shake Lancaster’s hand the bastard was standing with his hands behind his back. So after the take I said that he was supposed to shake hands with me and he said he was just improvising. So on the third take I kissed her but when I made a grab for Lancaster all I got was a good look at his surgical incision in the neighborhood of his kidneys. We made about six takes in all but our friendship is definitely on the rocks.

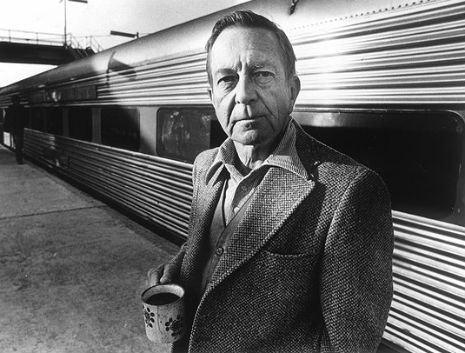

John Cheever was an established writer by the time the movie was made. He sold his first short story “Expelled From Prep School” in 1930 when he was eighteen years old. He sold his first story to the New Yorker two years later and went on to publish 120 stories with the magazine. His first novel The Wapshot Chronicle was published in 1957. Cheever originally intended his story “The Swimmer” as a full-length novel, with each chapter set in one of the 30 neighboring pools Ned swims across on his way home to his wife and family. He had been “kicking around” an idea of retelling the Greek myth of Narcisus which, according to his biographer Blake Bailey, was loosely inspired by his meeting Ned Rorem, with whom he had a brief sexual relationship, at an artist’s community in Saratoga Springs:

...[Cheever] had in mind a fellow Yaddo guest whom his meeting for the first time that September, composer Ned Rorem, who’d just broken his ankle and was hobbling about with a little plaster cast. As a reader of Freud, Cheever tended to equate homosexuality with narcissism, and in this respect the (almost) forty-year-old Rorem struck him as a kind of wistful, aging boy: “[H]e seems, in halflights, to represent the pure impetuousness of youth, the first flush of manhood, Cheever wrote. “He intends to be compared to a summer’s day, particularly its last hours and yet I think he is none of this.”

But the idea of retelling the Narcissus myth for modern day seemed slight, as Cheever noted in his journal for 1963:

I would like not to do the Swimmer as Narcissus. The possibility of a man’s becoming infatuated with his own image is there, dramatized by a certain odor of abnormality, but this is like picking out an unsound apple for celebration when the orchard is full of fine specimens.

Moving the story away from Narcissus gave Cheever greater freedom with his narrative, but he soon realized the main difficulty in writing the story as a novel was the impossibility of convincingly maintaining Ned Merrill’s delusions about his life over a long period of time:

The Swimmer might go through the seasons; I don’t know, but I know it is not Narcissus. Might the seasons change? Might the leaves turn and begin to fall? Might it grow cold? Might there be snow? But what is the meaning of this? One does not grow old in the space of an afternoon.

He further explained the struggle of writing “The Swimmer” in Conversations with John Cheever:

It was growing cold and quiet. It was turning into winter. Involuntarily. It was a terrible experience, writing that story. I was very unhappy. Not only I the narrator, but I John Cheever was crushed.

He edited his text down from 150 pages to about twelve, which meant the story moved seamlessly from one season to another within the space of a sentence. “The Swimmer” was published in the New Yorker on July 18, 1964, and became Cheever’s most famous story.

It was one of those midsummer Sundays when everyone sits around saying, “I drank too much last night.” You might have heard it whispered by the parishioners leaving church, heard it from the lips of the priest himself, struggling with his cassock in the vestiarium, heard it from the golf links and the tennis courts, heard it from the wildlife preserve where the leader of the Audubon group was suffering from a terrible hangover. “I drank too much,” said Donald Westerhazy. “We all drank too much,” said Lucinda Merrill. “It must have been the wine,” said Helen Westerhazy. “I drank too much of that claret.”

From this opening paragraph, the story subtly shifts to Neddy Merrill, who “might have been compared to a summer’s day, particularly the last hours of one,” sitting “by the green water, one hand in it, one around a glass of gin.” He’s been swimming and decides to swim home to his wife and four beautiful daughters by the “string of swimming pools, that quasi-subterranean stream that curved across the county.” He calls this connection of pools the “Lucinda River” after his wife.

The only maps and charts he had to go by were remembered or imaginary but these were clear enough.

Merrill plans his route by his neighbors’ homes, “the Grahams, the Hammers, the Lears, the Howlands, and the Crosscups. He would cross Ditmar Street to the Bunkers and come, after a short portage, to the Levys, the Welchers, and the public pool in Lancaster. Then there were the Hallorans, the Sachses, the Biswangers, Shirley Adams, the Gilmartins, and the Clydes.” At first he is greeted warmly, but slowly there are hints that things aren’t quite right:

“We’ve been terribly sorry to hear about all your misfortunes, Neddy.”

“My misfortunes?” Ned asked. “I don’t know what you mean.”

He continues on: in search of the next pool, the next drink—hardly aware of his failing physical state or the growing animosity of his neighbors.

“I’m swimming across the county.”

“Good Christ. Will you ever grow up?”

John Cheever reads ‘The Swimmer’

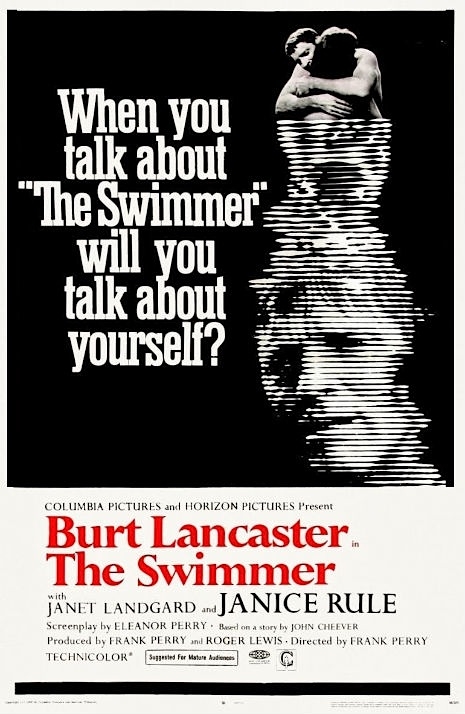

When the screenwriter Eleanor Perry read “The Swimmer,” she knew it would make a movie. With her husband director Frank Perry she had achieved some critical acclaim with their film David and Lisa in 1962. Now Eleanor felt she had found a suitable story for the pair to work on. But no one was interested, and the script drifted around Hollywood for two years until Sam Spiegel, producer of On the Waterfront, The Bridge Over the River Kwai and Lawrence of Arabia, picked it up.

As Natasha Fraser-Cavassoni puts it in her biography of the famous producer, the young couple were “thoroughly Spiegeled” by Sam’s award-winning track record, and wrote to him saying:

I’m afraid that both of us seem now to require your direct stimulation before we embark or agree on truly significant changes, in short we need you.

The couple signed up with Spiegel to make The Swimmer, giving over approval for the screenplay, casting, budget and final cut to his company Horizon.

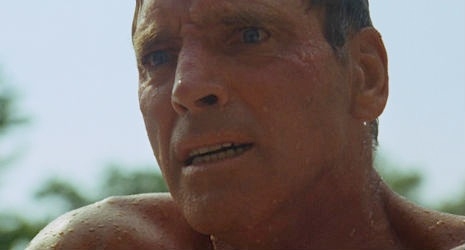

Siegel was executive producer, with Roger H. Lewis as producer, but this “detail had been vague” when Horizon chased Burt Lancaster to star as Ned Merrill. Lancaster described the story as:

Death of a Salesman in swimming trunks.

When Lancaster accepted the role, Spiegel wrote him a congratulatory letter:

It is most heartening to know that there are people like yourself, in Hollywood, with perception and courage and with an interest in films that go beyond the obvious and ordinary.

What Lancaster didn’t know was the part had been already turned down by William Holden, Paul Newman, George C. Scott and Glenn Ford. Showing his commitment to the project, the 52-year-old actor spent several months in training with Bob Horne, the head swimming coach at UCLA. But when it came to filming, Lancaster did not take well to producer Roger Lewis, nor to Frank Perry’s directing style, as Natasha Fraser-Cavassoni reported in her biography on Spiegel:

“It was not Frank’s nature to prepare,” said a Perry associate. “He had done that lovely little film [David and Lisa], but it was a ‘little film’ that was improvised. It had cost nickels and dimes. With Burt, not only was he an actor-star and a producer, but he was tough.”

The fights were endless, with Perry trying to settle their differences privately and the film star insisting that the cast and crew be privy to their disputes. “And [Lancaster] said, ‘I have balls. I do my fights in public,’ the director told Gary Fishgall. “So he made me do it in front of people. And the crowning blow was, ‘Look, kid, do you know how much I’m making on this picture?’”

Burt meets Joan Rivers

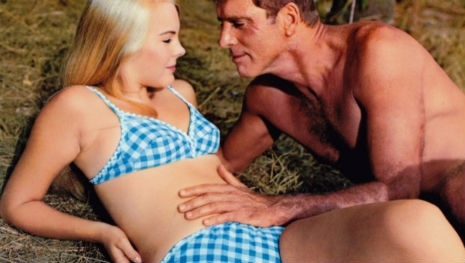

When Spiegel saw Perry’s 94-minute cut of the film he was “flummoxed” and thought there was no motivation for Ned swimming back to his home, and the film made no sense. Spiegel ordered additional scenes to be shot. Lancaster at first refused until Sydney Pollack was hired to “mop up.” Siegel also replaced Ned’s mistress played by Barbara Loden with Janice Rule, which horrified the Perrys, leading Eleanor Perry to write Siegel:

“Janice Rule may be a dear, sweet girl and a lovely person, but she hasn’t 1/10 the talent of Barbara…” [Eleanor] was considered to be more brilliant than her husband. “It was really thanks to her that Frank had the career he had,” said an acquaintance.

..Janice Rule’s scene with Lancaster was shot on February 8, 1967. “I took less than my normal fee,” she recalled. “And Sam said, ‘I’ll leave you my Chagall in my will.’ You know Les Amants, above his bed?” In fact, all of Spiegel’s paintings were either sold at Sotheby’s or given to the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. “I didn’t mind. That was Sam and I loved him for it.”

The reshoots continued, and Spiegel hired Marvin Hamlisch to compose the film’s core, which one reviewer said, “would sound overly passionate in a Verdi opera.”

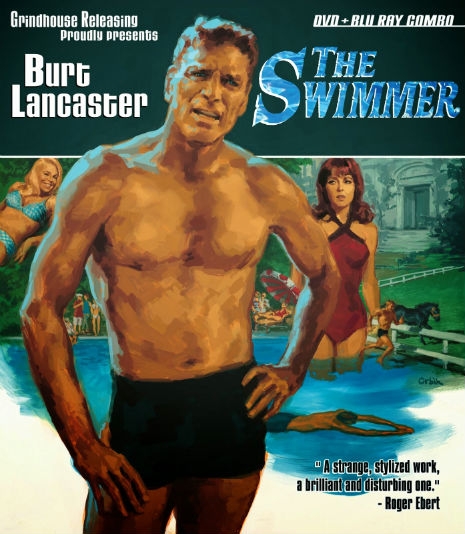

Two years after its initial shoot, The Swimmer was released in 1968 and received mainly positive reviews: Vincent Canby wrote in the New York Times the film stayed “in the memory like an echo that never quite disappears,” while Roger Ebert described it as “a strange, stylized work, a brilliant and disturbing one.” Author John Cheever thought it faithfully represented his original story, however, the film was a financial loss.

I saw The Swimmer on television when I was about thirteen and thought it a classic. In part because of Lancaster’s performance, but mostly because of the substance of Cheever’s story with its theme of “the irreversibility of human conduct,” allowed an audience to read the “The Swimmer” or view the film as a pertinent allegory for their time—and this is what makes for great fiction.