If it’s ever been your dream to produce a feature film, the good news is it’s easier and cheaper than ever. In fact, I just did exactly that and I’d like to share some thoughts and experiences on the process with any first-time would-be filmmakers out there looking to get started. I’m talking about doing it on the cheap.

First, a bit of background: I’ve always wanted to make movies. When it came time to go to college I couldn’t afford to go to a fancy film school, so I studied Media Arts at the local university. The degree I received was, in practicality, fairly worthless, and my college experience, if anything, dissuaded my interest in film. The curriculum pushed students toward industrial videos and commercial work—and that held no interest for me at all. I got out of college and, instead of going to Hollywood to gofer coffee for actors and execs on movie sets, I opened a record store. Records are my other great love. And so I have worked in record stores ever since, for twenty years, with the idea still always in the back of my mind “one day I’m gonna make movies.” Until, finally, one day I realized that I wasn’t getting any younger and it was time to either shit or get off the pot.

There were two catalysts that ultimately resulted in me producing and directing my first feature (which I just completed this month). The first was the inspiration of a filmmaker in my hometown named Tommy Faircloth who had made a horror feature called Dollface in 2014 for under $10,000. Citizen Kane, Dollface was not, but it looked and felt enough like a “real movie” to get me really excited about what one could be capable of on an extreme micro-budget. The second catalyst was my friend David Axe, a war journalist and would-be screenwriter expressing some frustration over breaking through in Hollywood. My thought at the time was “if I’ve always wanted to make a movie, and you’re trying to get your words on the screen, and if our friend Tommy can make a movie for less than $10K, then what are we waiting for? Why don’t we just get our act together and make a movie?”

We entered into “our first feature” looking at it as a “learning exercise” and I think this is an important attitude to have. Your first movie is bound to have a lot of mistakes, but you can look at the overall project as a success if you learn from any mistakes made. It doesn’t necessarily have to be good... it just has to be.

Ultimately, we decided that we were going to make a movie to learn how to make a movie and the only unbreakable rule we set for ourselves was “no matter what, no matter how disappointed we might possibly be with the end result, we have to FINISH THE PROJECT.” In hindsight, that was the perfect gameplan. If you know that finishing is a foregone conclusion, then that frees you up to concentrate more on the details of getting to that finish line. Ultimately, I ended up with very few disappointments in our completed product outside of some intermittently imperfect framing, lighting, and audio. If you go into the project with this attitude then the only way to fail is to do nothing.

And so David and I moved forward, brainstorming the things we could afford to put into a movie as far as locations, actors, and effects go. You have to use locations you can access for free. You have to have a small cast—ours was probably too big.

We made an “Exploitation 101” laundry list, informed by the entire history of low-budget cinema, of items to include in our feature to make up for the fact that our film would have no name actors and would likely suffer from dodgy production value.

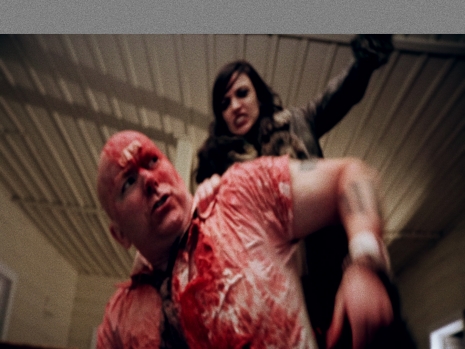

If you are looking to make your first no-budget feature, I highly recommend going the genre route… particularly horror. Horror fans are extremely forgiving of production quality and non-professional acting as long as the story is interesting. For us, it helped that my favorite movies are essentially horror and exploitation films ANYWAY, but it’s a hell of a lot easier to find an audience for a cheapo slasher flick than it is for a cheapo rom-com. Without going into great detail about our list, essentially we were looking at some form of sex, violence, or general strangeness at least every five script pages. If you don’t titillate your audience every five minutes, they are going to start to notice, say, how shitty your lighting is. I mean, they’re going to notice that anyway, but they are much more forgiving if they are constantly distracted from it.

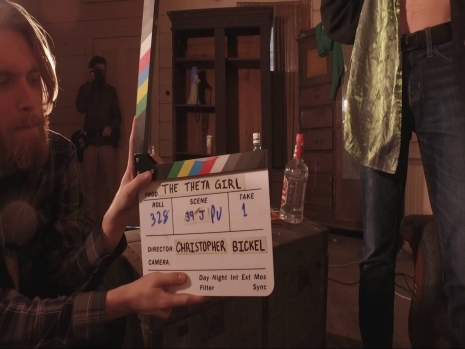

From that list, David wrote the script for our first feature, The Theta Girl, a psychedelic horror revenge story.

Our story contained all of the “Exploitation 101” elements we had laid out, but it also attempted to subvert some of those tropes. We also made sure it passed the Bechdel Test— because movies should do that anyway (though, to be fair, the horror genre as a whole tends to be better about this than most other genres).

One thing that was important to us, and I will offer this as a bit of advice to new filmmakers: make a film that can be categorized as a genre film, but DO NOT remake shit people have already seen. A $10,000 version of Friday the 13th is not only unnecessary, but it’s likely to be boring, and it certainly won’t win you any word-of-mouth unless you are able to go way-the-fuck-over-the-top with the kills. The best thing you can do as a new filmmaker, working under the duress of a microscopic budget, is to make a film that’s sort of like other things that people already enjoy, but also totally fucking different from everything else. Granted, this isn’t the easiest thing in the world, but no matter what your budget is, imagination is free (unless you’re paying a screenwriter—but if you can afford to do that, then why are you reading this?)

So what did we do next? What should you do next once you have an entertaining story ready to go? We brought in people to work and made the decision to pay everyone on our production. Not much, mind you… but enough to make it worthwhile for actors and crew to show up on set. Now you could (and a lot of people do) make a film with an all-volunteer cast and crew, but I am going to tell you from my first-timer experience that unpaid people will quit the first day that everything sucks… and you will have plenty of days where everything sucks. I’ll get more into this later, but making movies is really, really, really, really fucking hard.

I suggest paying a day rate to your cast and crew and have them sign a contract stating that they will be paid at the end of production for all days worked, but the contract becomes void if they quit before the end of production. This contract is assurance that the crew members will be paid, but also your insurance that the actors won’t bail on the project after you have 3/4 of the thing shot. Make meticulous records of days worked. Treat everyone fairly. Pay them as soon as you wrap shooting. We paid a flat $50 a day for every actor and crew person. This is admittedly jack-shit, but it was what we could afford and just enough to keep everyone motivated.

Having made that decision to pay or not to pay (PAY THEM!), you can then do a casting call and find some crew. Working on a mega-low budget means you will probably be hiring inexperienced crew who are looking to learn. Give them the opportunity to learn with you and allow them some room to fuck up with you.

Paying everyone meant that we were going to be spending a bit more than we had originally thought when the script was written. In hindsight, our script was rather (as one filmmaker friend delicately put it) “ambitious,” and probably a bite bigger than we had any right chewing.

Full disclosure here, it actually cost us $14,000 to make The Theta Girl, but had I known then what I know now, with better planning, we could have easily brought it in at $10K. Unfortunately, without ever having made a movie, there’s no real way to know how to plan your shooting days until you’ve actually done it. We ended up spending much of our budget paying multiple actors and crew members for multiple days that could have been more efficiently scheduled. My advice to new filmmakers on this front is: read as much as you can about pre-production. Plan for EVERYTHING. Think of every possible contingency. Storyboard everything. Create shotlists that you will stick to during production. Assume low-paid actors are going to be late a lot and have someone on your team whose job it is to pleasantly harass and wrangle them into being where they are supposed to be when you need them.

Knowing that money was likely to be extremely tight, we decided to do a crowd-funding campaign for our project. Now, in general, I’m not a huge fan of crowd-funding campaigns, but there is a way to do them “right” and, in retrospect, I think the crowd-funding campaign is a really smart idea beyond money generation. First of all, don’t be an entitled asshole with your campaign. No one owes you anything for “being cool” or making something that only you think is “awesome.” The best way to manage your campaign is to “pre-sell” your film or items related to your film. You can also “sell” roles and production credits. If people believe in your project, they will be more than happy to contribute. How will they believe in it? You must demonstrate that you are serious and capable, and that can take a bit of convincing. For us, having never made a movie before, the big looming question was “how do we demonstrate that we are capable of doing this?” It’s not like I had a showreel. I’d never made a movie before. Ever.

So what we did was this: We made a trailer for a fake movie in order to demonstrate that we could operate our gear and edit something together into a cohesive and entertaining form. This fake movie trailer also served the immeasurably benefitting purpose of allowing us to work with the actors we had just cast and the crew members we brought on board. It was also a good dry-run at learning how to direct and edit on a smaller scale before jumping totally into the deep end of a 90-minute feature head-first. It allowed us to make sure none of our hires were flakes or divas (they weren’t!). We decided to make a trailer for an imaginary movie INSTEAD of a direct trailer to The Theta Girl because we wanted to keep some element of mystery as to what our feature was going to be.

Here is the trailer for the fake movie, Teenage Caligula... the first thing I ever shot, and a major learning experience:

Showing proof of our ability to see something through till the end gave backers enough confidence to donate to our campaign. It also served as a sort of commercial for our campaign, which brought in even more supporters. Ultimately, what the crowd-funding campaign accomplished was much more than the money: it gave our film it’s first fan-base, sight-unseen. We suddenly had a group of people who were emotionally invested in seeing our film succeed. They became our first “street-team.” Even if you already have the money in hand to produce your first low-budget feature, I’d still recommend doing a crowd-funding campaign to build an audience and buzz around your project. The people who donate to your campaign will be your forever cheerleaders.

Once all of the pre-production rigamarole of hiring people, raising money, doing shot lists, storyboards, and scheduling work days is finished, you jump into the production. This is the most grueling aspect of the process, but it can also be the most fun… if you’re lucky, everyone will feel like they are fighting in the trenches with you and end up becoming family. This is also where you will learn EVERYTHING about how a movie is made, because if you are making this movie for $10K or less, you will be doing pretty much every single job at some point. You know when the credits roll on a major Hollywood film and there’s like 500 people listed? On your movie, you will be 300 of those people.

I should mention here that I was working a 40-hour-a-week day-job in addition to submitting at least one article a week to Dangerous Minds throughout the entire process of making my first film. I’m saying this to neither brag nor to cry “woe-is-me,” but rather to underline the fact that YOU CAN DO THE SAME. If you want to make a film bad enough, you will make the time. Be prepared to give up your social life for a solid year (assuming you will also be the editor of the film, because you certainly can’t afford an editor on your budget, now can you?), and be prepared to be more stressed out than you’ve ever been in your life, and be prepared to alter your sleep schedule to 4 or 5 hour nights… but you CAN totally do it. Working 40-hours-a-week is not an excuse to delay your dream. If you want it, you will make the time. I was directing and shooting in addition to assisting in costuming, set-design, lighting, and even acting a bit. If you are making a movie on the ultra-cheap, you can’t afford to pay anyone else to do this stuff. I can’t tell you HOW to do all of this stuff in the space of this article, but I can tell you that it’s DOABLE. The how-to information is out there. Specifically, I recommend the YouTube channels of Film Riot, Indie Film Hustle, and This Guy Edits, among others.

I should mention here that a lot of your time will be spent figuring out how to make gear and sets out of cheap materials. Borrow as much shit as you can. I didn’t include gear in our film’s budget because I had already bought the inexpensive cameras I used to shoot The Theta Girl. Specifically, I used a Canon 80D, a DJI Osmo, and a GoPro Hero 4 Black. These are all inexpensive consumer grade cameras that are still capable of creating cinematic images. If you needed to factor a camera into your budget, you could get away with spending $500 for a decent enough used camera and lenses to shoot a feature. You can buy cheap work lights at Lowes or Home Depot that may not be “Hollywood pretty” but they will light a scene—sometimes better than other times, depending on your level of previous lighting experience. Let’s just say I had a lot of “learning opportunities” on my film with some less-than-glamourous lighting. But you know what? I have as much of a right as any filmmaker to declare that that was intended to be “the look” of my film, right? Your mileage may vary.

When you are in production MAKE SURE YOU GET GOOD SOUND. Bad sound is the hallmark of an amateur production and it’s the number one thing that had me pulling my hair out during post-production. Get a decent mic. Splurge the few hundred bucks for a good pre-amp (I didn’t and wished I did). Make sure your sound person knows how close to get to the actors. Don’t fart around on the sound. It’s equally as important as the visual. I might even make the argument that it’s more important: it’s easier to follow a narrative with sound on/video off than it is to follow with sound off/video on. Also, viewers fatigue from bad audio much more quickly than from muddy visuals. Get good sound.

If you are shooting as well as directing like I did, make the time to get extras takes and review the footage. I didn’t always do that and was left with a few weak performances and some shots that didn’t cut together very well. The attention you pay to the actors’ performances will be lacking when you are also trying to keep them in focus and in frame. If you don’t have a DP (how could you possibly afford one?), then you are going to HAVE to make the time to review the performances before moving forward to the next shot. Otherwise, your direction is going to suffer because your attention is on camerawork. Try to have an assistant to be keenly aware of continuity. Sure, goofs can be charming sometimes, but you do want to try to avoid them if at all possible. (No matter how hard you try, you are still going to have them.)

Be aware that if you have never made a film before, you are going to get very frustrated on set. Things will not go your way all of the time. People can be unprepared, locations can fall through, actors can get sick, lights can break, cameras can malfunction. The number one key to success that I learned on making my first film is to always suck it up, try not to let the frustration overtake you. Roll with the punches, regroup and figure out what work can be done INSTEAD of the work you had planned for. Don’t ever stop if people are on the clock. Get as much as you can despite any unforeseen disasters. Sometimes these circumstances will present a different way of looking at things. Sometimes they will even make your film better. TRY, try, try not to yell at people. It will be hard sometimes. Just don’t ever throw in the towel.

We had one instance where we had hired three (real) cops for three hours to shoot a car chase on a set of deserted roads. It was our single biggest expense on the production. On the morning of the shoot the cops showed up and their commanding officer had not told them they were going to be in a movie! They thought they were doing security for a shoot! So once we spent the time to convince them to actually appear onscreen in our movie, we had learned THAT VERY MORNING that the entrance to the location where we were going to shoot had been chained, barricaded, and posted with “no trespassing” signs. You can’t exactly “guerrilla film” that when your actors are officers of the law. So we had to figure out a place to film QUICK or blow our budget paying for cops we couldn’t shoot. I asked the cops if they knew of any deserted roads we could shoot on. After an hour, one of the cops remembered a subdivision under construction that we could drive through. It was a 45-minute drive away. So, by the time we got to the location, we had only one hour to shoot a whole chase scene in a brand new location. So the shot list was basically thrown out the window. This was where it was important to not become frustrated. I just shot as many wild shots of cars chasing cars as I could, trying to bear in mind what would likely cut together. Amazingly, it all DID work… even despite the fact that the cops got a call of a real-life murder and had to leave the (already 2 hours late) shoot 15 minutes early. We ended up only having them for 45 minutes! I thought we would have to throw out the entire scene, but persevering and getting as many shots as possible resulted in a scene that actually works. An audience member at one screening of the finished film cited it as their favorite scene. Go figure.

When the shooting has wrapped you are left with a mountain of footage and sound recordings. It’s then up to you to somehow put all of that together into a coherent and entertaining form. There is no way to learn editing from reading or watching tutorials. You have to learn from doing it. Your first time out, the editing process is going to take a lot longer because you are likely going to cut every shot too long and you will have to cut and recut and recut again until your film finally starts to feel like a “real movie.” You will need brutally honest friends to help you determine what “babies” you kill in the editing room. You will learn how to cut on eye movements just because through trial and error you will get a second sense for what “feels right” in an edit. It is during this post-production time that you will also learn how to color correct to get a particular look or feel (on The Theta Girl I went for “movie shot on 16mm in 1983 with a $150,000 budget”—in 2017 you can sort of pull that off for $14,000).

You will also learn the supreme importance of sound design and music. That’s the part that REALLY makes your movie either something special or a pile of crap, because the sound is what “sells” all of the action on screen. You really have NO IDEA how important this is until you actually look at your edited footage with and without music and sound effects. It is EVERYTHING. Make sure you spend as much time on the sound editing as you do on cutting your footage. If you’re anything like me, you’ll end up having like twenty “final cuts”—always look for more stuff to trim down. Keeping things moving is of supreme importance on a no-budget feature.

Finally, when you have something that you think is “finished” you can be proud of the fact that you completed a feature film—something the majority of people who call themselves “filmmakers” never do. It is then that you make the decision to go the festival circuit and look for a distributor or go some sort of self-distribution route. The Internet has opened up a lot of avenues for self-distribution. With our film, we are currently playing festivals, and entertaining distribution offers. Ultimately, we will decide to either take an offer or distribute ourselves after building an audience on the festival circuit. To that end, we are generally submitting to smaller genre festivals to laser-focus on horror fans rather than trying to get into larger indie festivals. Winning awards doesn’t mean as much to us as getting sympathetic eyes on our film.

I would have liked to go into more detail on each of the individual aspects of pre-production, production, post-production, and promotion—about specific ways we cut corners and saved money, but that would be a book instead of an article. And maybe it will be one day—or at least a DVD commentary track. I mostly just wanted to communicate the idea that making your own feature film at an affordable price is completely within the realm of reason, and hopefully, inspire someone to do so. The technology to do this so cheaply did not exist when I was in my 20s. I wish it had, because then I’d be a lot farther along now… but the other takeaway from this should be that it’s never too late to make your dreams come true—even if your dream is simply to make a low budget gore movie!

I also realize that $10,000 is a lot of money to most people. It’s an enormous amount of money to me, and I couldn’t have done it without a business partner and a crowd-funding campaign. If you happen to have a crew of people absolutely willing to work as unpaid volunteers, you can do it for much, much cheaper. If you already own your own camera, technically you could make a feature film for the cost of SD cards.

In a way, everything I learned about making movies came from playing in punk bands, and I think anyone who came out of that background already has the strong D.I.Y. foundation necessary for making a no-budget feature. I remember what it was like coming up in a music scene where you would find “professional musicians” who spent lots of money on gear and expensive demo recordings, hoping to shop those demos to a label who would sign them for a bunch of money and they’d be the next Pearl Jam or whatever. And then there were the hardcore bands that didn’t care so much about the technical aspects of virtuoso playing or having pricey gear—they just had a lot to say and wanted to communicate ideas—so they made cheap records which they put out themselves and booked their own tours and went all over the world while the pros were still waiting at home for someone to tell them they had “made it.” If you go into filmmaking with the punk rock attitude that you want to tell a story, and the story means more than the technique, and engaging with an audience is more important than making money, and gaining an experience from the process is more important than receiving accolades, then you’re already a step ahead of the guy waiting till he can afford a Red Epic before he shoots his first $100K short.

You can do this.

BTS photo of “The Theta Girl” shoot by Sean Rayford.

(The Theta Girl is currently playing festivals across the United States.)