The great film director Ken Russell once remarked that if he had been born in Italy and called, say, “Russellini” then critics would have thrown bouquets at his feet. He was correct as Russell’s worst critics were generally slow-witted, myopic beasts, lacking in imagination and untrustworthy in their judgement.

Take for example the critic Alexander Walker who once dismissed Russell’s masterpiece The Devils as:

...the masturbatory fantasies of a Roman Catholic boyhood.

Walker was being petty and spiteful. He was also badly misinformed. Russell was not born a Catholic, he became one in his twenties and was lapsed by the time he made The Devils. More damningly, if Walker had taken a moment to make himself cognisant with Russell’s source material—a successful West End play by John Whiting commissioned by Sir Peter Hall for the Royal Shakespeare Company or its precursor the non-fiction book The Devils of Loudon by Aldous Huxley—then he would have realised Russell’s film was based on historical fact and his so-called excesses were very tame compared to the recorded events. However, Walker’s waspish comments became his claim to fame—especially after he was royally slapped by Russell with a rolled-up copy of his review on a TV chat show in 1971—Russell later said he wished it had been an iron bar rather than a newspaper.

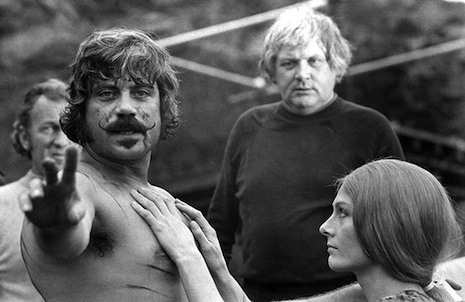

Oliver Reed as Grandier and Vanessa Redgrave as Sister Jeanne rehearse under the watchful eye of Ken Russell.

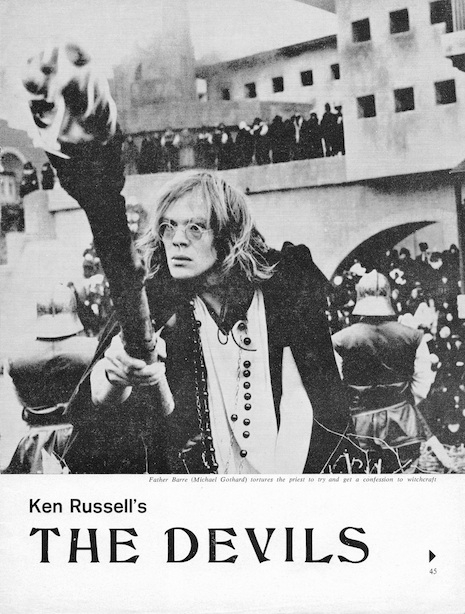

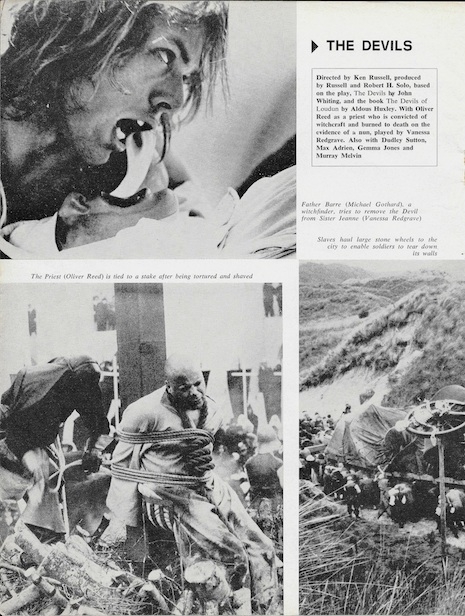

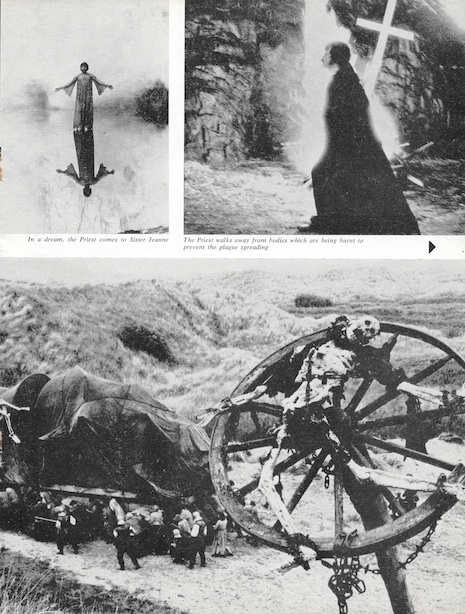

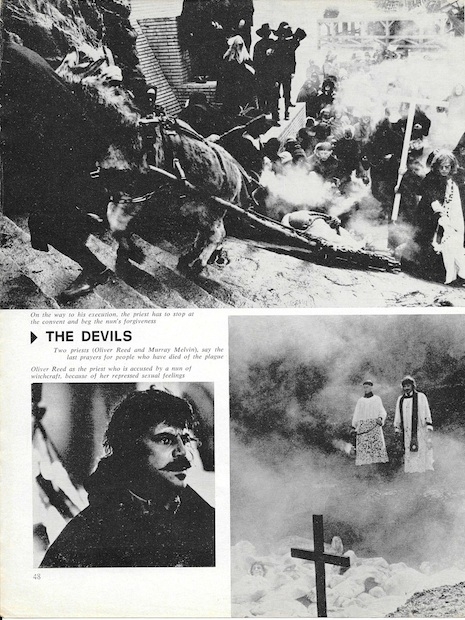

The Devils is the story of a priest named Urbain Grandier and his battle against the ambitions of Church and State to eradicate the independence of the French town of Loudon. In a bid to have this troublesome priest silenced, Grandier was tried for sorcery after a confession was brutally extracted from a nun, Sister Jeanne, who claimed he was an emissary of the Devil. Grandier was acquitted of all charges but a second show trial found him guilty and he was tortured and burnt at the stake. Russell described Grandier’s case as “the first well-documented political trial in history.”

There were others, of course, going back to Christ, but this had a particularly modern ring to it which appealed to me. He was also like many of my heroic characters…great despite himself. Most of the people in my films are taken by surprise, like [the dancer] Isadora Duncan and [the composer] Delius. They’re out of step with their times and their society, but nevertheless manage to produce rather extraordinary changes in attitude and events. This was exactly Grandier’s situation. He was a minor priest who was used as a fall guy in a political conflict, who lost his life and his battle but won the war.

After that they [the Church and State] couldn’t go on doing what they were doing in quite the same way, and around that time [1634] the Church did begin to lose its power. Twenty years later no one could have been burned as a witch in France. The people of Loudon realised too late that this man they knew so well simply couldn’t have been guilty of the things he was charged with, and if they hadn’t been so bemused by the naked nun sideshow that was going on and the business and prosperity it brought to the town, they’d have realised it sooner. So the fall guy achieved as much in the end as if he had been a saint. And to me that’s just what he is.

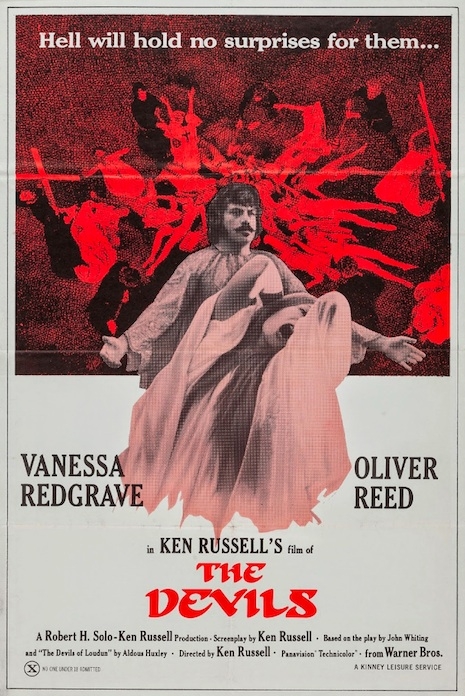

Though Russell was on a high after his international success with the Oscar-winning Women in Love (1969) starring Glenda Jackson, Alan Bates, Oliver Reed and Jennie Linden, and The Music Lovers (1970) a flamboyant biopic on the life of Tchaikovsky with Richard Chamberlain and Glenda Jackson, he had found it difficult to find a backer for The Devils. Original producers United Artists pulled out, leaving Russell “out on a limb: having written a script and commissioned set designs from Derek Jarman and costume designs from Shirley Russell.

It would have been a disaster to scrap all that work. Bob Solo, the producer, who had spent years getting the rights to Huxley’s book and Whiting’s play started looking around for another backer, but it took four months of offering the package before Warner Brothers agreed to have a go.

Russell’s script was considered too long and cuts were made. He had originally made Sister Jeanne the focus of his story, following the nun through her involvement in Grandier’s execution to her career as a star:

I suppose it’s the film that turned out most like I wanted it to, though I would have liked to carry the story further to show what happened to [Cardinal] Richelieu and Sister Jeanne. At the end de Laubardemont says “You’re stuck in this convent for life”, but as soon as he’d gone Jeanne set about getting out because her brief moment of notoriety had whetted her appetite for more. So she gouged a couple of holes in her hands and pretended she had the stigmata, saw ‘visions’ and, with the help of Sister Agnes, gulled some old priest into thinking she was the greatest lady since the Virgin Mary.

So she and Agnes went on a jaunt all over France and were hailed with as much fervour as show biz personalities and pop stars are received today. In Paris 30,000 people assembled outside of her hotel just in the chance of getting a glimpse of her. She became very friendly with Richelieu, the King and Queen wined and dined her, she had a grand old time. When she died—I particularly wanted to include this scene—they cut off her head and put it in a glass casket and stuck it on the altar in her own convent. People came on their knees from miles around to pay her homage.

Glenda Jackson was originally cast as Sister Jeanne but dropped out after Russell cut the script—she thought it would be too like her previous role in The Music Lovers ending up “back in the madhouse again.” Vanessa Redgrave was cast as Jeanne with Russell’s favourite actor Oliver Reed taking the role of priest Urbain Grandier.

Ken Russell interview in 1971 on the making of The Devils.

Russell described The Devils as “a harsh film—but it’s a harsh subject matter.”

I wish the people who were horrified and appalled by it had read the book, because the bare facts are far more horrible than anything in the film. But the word has to be translated, interpreted, if necessary censored—the image is immediate, irrefutable.

I remember one particular line of Huxley’s; “The purging of Sister Jeanne was the equivalent of a rape in a public lavatory”. Well, I don’t know if people reading the book had any real understanding of the horror of that image but since I was filming the book I had to convey just what it meant. The chapel looks like a public lavatory, all white tiles—you couldn’t find a more unsympathetic place for a torture chamber—and I took that as my cue for the whole scene.

Then take a phrase like, “They analysed her vomit”. It’s in the book but people don’t believe it or can’t visualise it. The list of things in the vomit as exactly the one the inquisitors gave (saving the carrot) and I think that, for a lot of people, the film was the first insight into what a holy interrogation in those days was really all about. The inclusion of the comic line about the carrot was typical of many deliberate ludicrous touches throughout the film, designed to point out the nonsensical irony of these horrors being committed in the name of God.

Oliver Reed later developed this theme when he discussed The Devils on the chat show Parkinson, tying the horrors committed in the name of God to the Troubles in Northern Ireland, where religion and politics had once again divided a country and set its people murderously against each other.

We made that film because we thought it was the proper time and in light maybe of the Troubles in Ulster now, it was the proper time for that film to be made. We weren’t trying to afford anybody proper niceties, any proper little entertainments, little asides before tea, we were showing them the bigotry that goes on, or that humanity is capable of, and that was all we were doing.

Oliver Reed discusses ‘The Devils’ on Michael Parkinson’s chat show.

Russell only one real regret over The Devils was having to remove “the real core of the film, the Rape of Christ.” In this infamous sequence the nuns, feigning possession, tear down a giant crucifix and “throw themselves upon it in every possible way.”

Then [Father] Mignon [Murray Melvin] goes up into the roof and masturbates looking down on the orgy below. Both warner Brothers and the censor thought it too strong so I took it out. Short of burning the whole film I had no choice. But it was really central to the whole thing, intercut as it was with Grandier finding both himself and God in the solitary simplicity of Nature. Over-ripe, perverted religion going as bad and wrong as it can possibly become, with the eternal truth of bread and wine and the brotherhood of man and God in the universe. Try getting the Hollywood heavies or the Festival of Light to swallow that!

Ken Russell was the Picasso of cinema and one of the most important film directors of the second half of the twentieth century. He invented new forms of storytelling—the drama-documentary through TV films like Elgar before reinventing it with scriptwriter Melvyn Bragg in his biopics on Delius and later The Music Lovers; before creating complex comic strip movies Dance of the Seven Veils, Tommy and Lisztomania that devised a new form of cinematic language which is continued and developed in the work of directors as different as Derek Jarman (Caravaggio), Danny Boyle (Trainspotting) and Ben Wheatley (A Field in England). The Devils is the equivalent of Picasso’s painting “Guernica”—a work of art that confronts the audience with the barbaric inhumanity of fundamentalist religion/politics—whether as practiced by corrupt Christians or the insane followers of the death cult Daesh, which makes Ken Russell’s film as relevant today as when it was first released.

Previously on Dangerous Minds

What a pact with the Devil (supposedly) looks like.