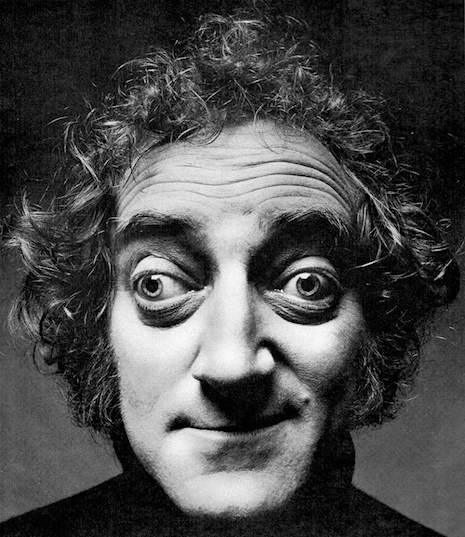

Marty Feldman said his distinctive looks were “the product of a thyroid condition caused by an accident when somebody stuck a pencil in my eye when I was a boy.” Whether true or not, it made Feldman instantly recognizable and in a way led to his breakthrough role in America as the scene stealing Igor in Mel Brooks’ Young Frankenstein. Feldman later quipped he was the only man to appear in a horror film without make-up.

Feldman was a hero, a rebel, a maverick. A comedy genius who co-wrote with Barry Took some of the best British TV and radio comedy during the 1960s. When he moved to Hollywood in the 1970s, his movie career started brightly and ended dismally—he died during the making of his last feature Yellowbeard.

Born to Jewish immigrant parents in Canning Town, London in 1934, Feldman was a wild and rebellious child, constantly in trouble and expelled from several schools. He later claimed he had a lot of violence which he eventually exorcised through performing in shows.

He was anti-authoritarian. His attitude was “ya-boo-sucks.” England, he claimed, was a country that had “produced a great number of passionless mass murderers” or “little bank clerks, the neighbourhood doctor. They all have the sort of bald, bony heads and wear pebble dash lenses and raincoats.” When considering this, one has to ask, what he made of West Coast America with its serial killers and shopwindow sincerity?

A tip of the hat to Marty’s comedy hero Buster Keaton.

He left school with no prospects but a great desire, a burning desire to do something creative—anything creative. He followed the beatnik trail to Paris. Feldman loved jazz. He played trumpet. He was apparently so bad he was once described as the “world’s worst trumpet player.” Whether true or not, jazz was the first avenue Feldman tried to map. He met his idol Charlie Parker in Paris. But the great jazz legend could only talk about snooker much to Feldman’s chagrin.

He adopted the jazz life—smoking weed, eating bennies and shooting junk. It wasn’t for him. He returned to England and worked in fairgrounds. He then started working in repertory theater where he met his future writing partner Barry Took.

Feldman and Took were among the most significant comedy writers in England during the 1950s and 1960s. Together they wrote classic comedy sitcoms like The Army Game and Bootsie and Snudge. While for radio, the world will be eternally grateful for Round the Horne and the creation of two Polari-speaking omi-palones Julian and Sandy.

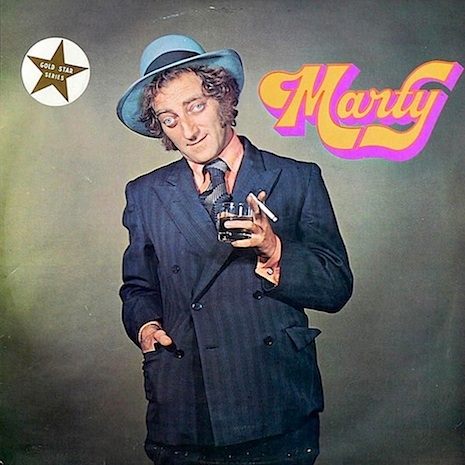

Feldman also co-wrote two of British TV’s best known comedy routines—the “Class Sketch” for David Frost’s show (which starred a young John Cleese) and “The Four Yorkshiremen Sketch”—which is now best known as being part of Monty Python’s oeuvre. It was inevitable that Feldman would one day make the transition from being a much sought after writer to a much-loved performer. He joined John Cleese, Graham Chapman and Tim Brooke-Taylor for At Last, The 1948 Show before having his own award-winning series Marty in 1967.

My memory has merged whether it was watching re-runs of Bootsie and Snudge or listening to Round the Horne on radio that supplied my first introduction to Marty Feldman. I knew his name before I saw his lovable bug-eyed face. My parents didn’t start regularly renting a TV until The Virginian and Alias Smith & Jones arrived in the 1970s. So if the former then I discovered Feldman’s work at my grandparents—where I spent holidays and watched an inordinate amount of TV. If the radio—then at home where music was background noise and comedies and serials given near religious observance. Radio was still a major source of entertainment. Television sets were too expensive to buy. They were big monstrous boxes that took up one corner of a living room. Most people (as my parents did) rented their TVs back in the sixties and seventies—paying a monthly check to Radio Rentals or Granada for a black & white box of delights.

Whichever, I do recall Feldman was a favorite subject for conversation at school, where his madcap stunts were discussed with the passion of a prosecuting counsel questioning a prime witness but usually in between bouts of playing soccer or British Bulldogs. Even my grandmother whose preference was mainly sitcoms and soaps On the Buses, Doctor in the House, Peyton Place, Doctor Kildare and Coronation Street liked Feldman—he was cross generational. Everyone loved Marty. Even Marty loved Marty. And that became a problem.

According to his fellow writers and performers (Michael Palin, John Cleese), Marty’s success as a TV comedy star and hit comedy writer “went to his head.” Which may or may not be true—as both Palin and Cleese were hungry for their own success and could only watch as Feldman grew and grew like some cork-screw haired monster. But Feldman was only following a linear career progression from stage to radio to television to film. And so, eventually, to Hollywood.

Yet, with all his success, Marty remained an anarchistic rebel. He famously refused the offer of meeting Frank Sinatra reputedly saying “I don’t like his politics.” Ole Blue Eyes was not amused. In the early 1970s, he risked his reputation by giving evidence in support of Richard Neville and co. at the infamous Oz trial, where Feldman cheekily asked the judge—a curmudgeonly old reptile—if his testimony was keeping him awake? Eventually, he came to dislike the gaudy world of Hollywood and apparently preferred to spend his time playing soccer with a team of waiters and regular working joes, who had a better grasp of what was important in life—probably wine, soccer and amore.

These days TV commissioners are not happy with just a straightforward biography rather they always have to impose some form of artificial construction onto a story. This is what happens here in Marty Feldman Six Degrees of Separation, which uses the trope about Kevin Bacon and attempts to make some sense of Feldman’s incredible connections to the world of comedy. Thankfully, the filmmakers gave up on this idea and stick with just telling the viewer all about Feldman’s life—which was packed full of enough good things to fill up—oooh, let’s say—-at the very least one hundred good documentaries.