Allen Ginsberg was a hustler. He was always on the make. But if Ginsberg was getting a piece of the pie then everyone was getting some pie—that was the kind of guy he was.

In 1953, Ginsberg was one of the young writers loosely identified as the Beat Generation. There was Jack Kerouac—nominally the Beat daddio who had his first book The Town and the City published in 1950. It was a coming of age novel that lacked the Beat prosody (“spontaneous prose”) that illuminated Kerouac’s later, better known work.

There was John Clellon Holmes who had written Go—a depiction of the hip counter culture world of parties, drugs, jazz and “the search for experience and for love.”

And then there was William S. Burroughs.

Ginsberg had encouraged Burroughs to write. He grooved over the letters he wrote—he dug his style. He told Burroughs to write a book about his experiences as an unrepentant drug addict. Nelson Algren had already written and had published his tale of heroin addiction The Man with the Golden Arm in 1949. The book received rave reviews and won Algren a National Book Award. Ginsberg figured Burroughs—an actual junkie—could deliver a better, more powerful book if only he would sit down and write it.

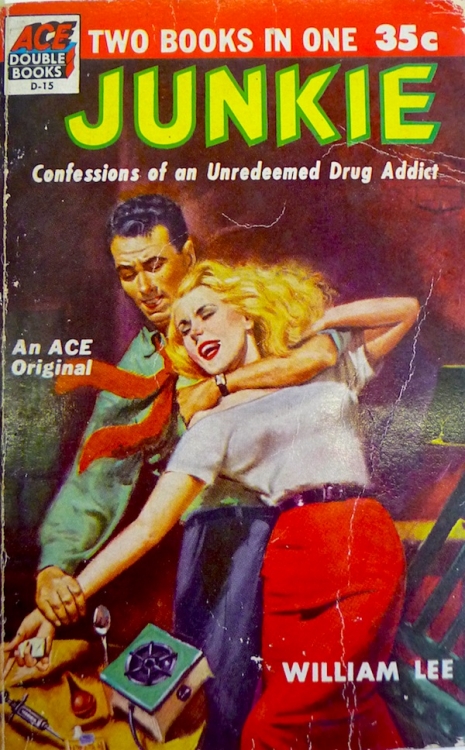

Burroughs grudgingly took the advice. He had already co-authored an as yet unpublished novel with Kerouac And the Hippos were Boiled in their Tanks in 1945 about the murder of friend and associate David Kammerer by one of the original Beat gang Lucien Carr. The book had been a literary experiment with Burroughs and Kerouac writing alternate chapters. Now he would give the facts of his life some color in the manner of Thomas De Quincey—writing the semi-autobiographical Junkie: Confessions of an Unredeemed Drug Addict.

Ginsberg helped edit the book. Then he brought it to Carl Solomon—a publisher contact he’d met at Greystone Park Psychiatric Hospital in New Jersey where both men received treatment. Solomon’s uncle was publisher A. A. Wyn—owner of the pulp paperback firm Ace Books. Through Ginsberg’s endeavors, Solomon convinced his uncle to publish Burroughs novel—written under the alias “William Lee”—as part of the Ace imprint.

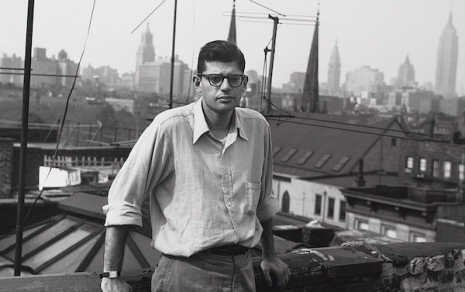

Ginsberg as ‘seen by Burroughs’ on the rooftop of his Lower East apartment, New York, 1953.

To help publicize Burroughs/Lee’s debut novel, Ginsberg rustled up some publicity and asked Holmes and Kerouac to give their support in a plug for the book for New York Times gossip columnist David Dempsey.

February 19, 1953

Thursday Night 10:30

“JOHN KEROUAC AND Clellon Holmes, both experts on the Beat Generation, Holmes through his recent Times Magazine section controversy, say that they “dig” the pseudonymous William Lee as one of the key figures of the Beat Generation.

“Lee first appeared lurking in the shadows of both their books, respectively The Town and the City and Go, portrayed as underground character. Lee’s professional debut in the open on his own as an author is announced by Ace Double Books with the publication of Junkey: The Confessions of an Unredeemed Junk Addict, which comes up from underground April 15.

“Author-Junky Lee has not stayed around to gather whatever plaudits are due and was last heard from on an expedition into the Amazon basin in search of a rare narcotic.”

In the accompanying letter, Ginsberg asked Kerouac:

Please give your permission for your name to be used, and also please send me, for now or later use, with this item, a two sentence plug for Bill [Burroughs] as intense and hi-class as you can make it, Twenty-five words or so. Holmes will contribute also—emphasizing literary value, whatever it is, personally, or perhaps balloonish foolishness of the whole project of JUNK.

Kerouac freaked out at this request. He fired off his response from his mother’s address….

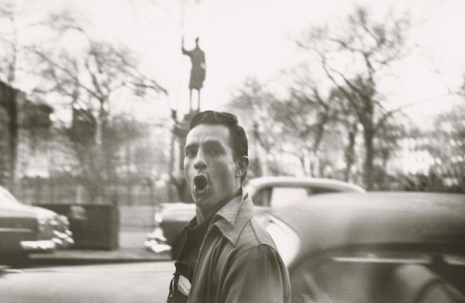

Kerouac by Ginsberg after a visit to Burroughs’ apartment making a ‘Dostoevsky mad-face or Russian basso be-bop OM.’

Feb. 21, 1953

Dear Allen and Sirs:

I do not give permission for my name to be used in the notes prepared by you and A.A. Wyn and Carl Solomon for David Dempsey’s New York Times literary notes column. I do not want my real name used in conjunction with habit forming drugs while a pseudonym conceals the real name of the author thus protecting hum from prosecution but not myself and moreover whose work at the expense of my name is being bruited for book trade reasons.

In this “rough draft publicity” I do not want The Town and the City mentioned in juxtaposition to Go, by association hinting at some professional and artistic semblance, and I deny permission to place my name next to Clellon Holmes as co-expert on the Beat Generation.

Especially I do not want to be misquoted as saying that I “dig the pseudonymous William Lee as one of the key figures of the Beat Generation.” My remarks are at your disposal through the proper channels, from my pen and through my agent.

Yours most respectfully and strictly business,

John Kerouac

Ginsberg’s request was the “Cause of Tiff” between the two men. Ginsberg was not to be out done by Kerouac finking out on him. He wrote a sarcastic and catty letter back making a dig at Kerouac’s prissiness and his relationship with Holmes and the publishers at Ace:

Before I proceed let me congratulate you on the charm and incisiveness of quotation which you authorize; which quotation I will naturally submit to your agent for his (her) approval before making use (there)of.

...While I approve your wish to dissociate your own literary position with that of the author of Go (who incidentally gave his general permission, etc. without consulting MCA) and while I will do everything in my power to aide you in doing so, especially in this instance, it behooves me to remind you as a friend that, by adopting your suggestion of separate statements, no further reference will be made by me to anyone that it was your request. In other words, let us do this as quietly as possible, so as not to risk offending Mr. Holmes. If you wish to make a public matter of this, of course, that is your privilege, and I will follow suit.

Secondly, you know of course that great secrecy is desirable vis-a-vis your new relationship with MCA, particularly as there is still a delicate situation to be dealt with at A.A. Wyn. Solomon knows nothing of recent activities. I have, by your express instructions, said nothing to him of any import on anything remotely concerning your present publishing position. So, if you do see him, and speak of this matter, or any other, I beg for your own sake to breathe not a word about MCA. And certainly, if you wish to see him, avoid MCA as intermediary, until they say so.

Deep down Kerouac was a square pretending to be hip. He was more afraid of what his mother thought—the one person who ruled his life—than what his friends did. Kerouac was thirty years of age.

This was a similar failing with William S. Burroughs—who was almost forty. He published Junkie under the pseudonym “William Lee” for fear of mommy and daddy cutting off his allowance.

There was a juvenile immaturity that connected the Beats which was best satirized by John Updike in his story for the New Yorker magazine “On the Sidewalk.”

In landsend despair I stood there stranded. Across the asphalt that was sufficiently semifluid to receive and embalm millions of starsharp stones and bravely gay candywrappers a drugs tore twinkled artificial enticement. But I was not allowed to cross the street. I stood on the gray curb thinking, They said I could cross it when I grew up, but what do they mean grown up? I’m thirty-nine now, and felt sad.

Kerouac was a law-and-order man. For all his joyous liberating prosody and his search for truth and meaning—he was a natural born Republican, who eventually came to hate the very generation of youngsters that his books inspired.

Ginsberg and Kerouac quickly kissed and made up. A tiff can only last so long with your playmates.

The above letters and more of their wondrous voluminous correspondence can be found in ‘Jack Kerouac Allen Ginsberg: The Letters.’ Below, Burroughs reads an extract from ‘Junkie.’