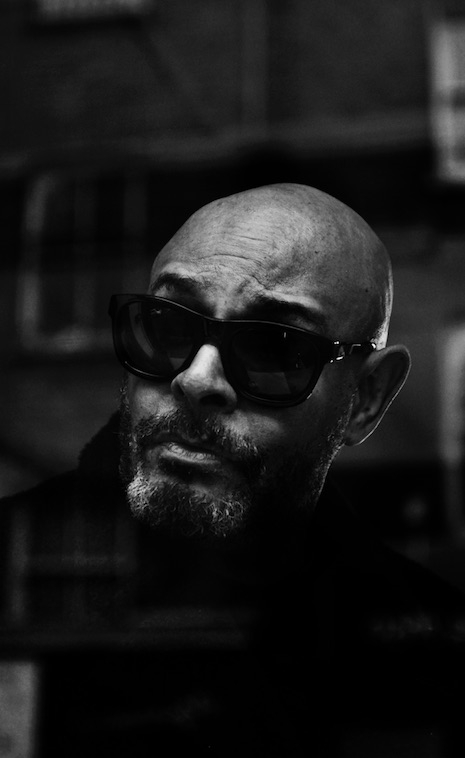

Barry Adamson is a musician, composer, writer, photographer and filmmaker. With those credentials, many people (journalists, critics, what-have-you) often describe Adamson as a “polymath.” Fair enough, but it’s not the full dollar. Coz I think Adamson is a fucking genius. And you can print that on a t-shirt and wear it with pride:

BARRY ADAMSON IS A FUCKING GENIUS

‘cause it’s true.

Over the past forty years, Adamson has produced some of the most startlingly original, uniquely brilliant, and utterly diverse music ever put to disc. His back catalog ranges from his time as bass player and co-writer with Howard Devoto’s hugely influential post-punk band Magazine, moving on through Visage, to joining the tail end of the Birthday Party before becoming one of the original key members of Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds. Quitting the Bad Seeds after their first four studio albums, Adamson delivered his debut solo album Moss Side Story in 1989—a dark and epic “filmic suite” to an as-yet unmade movie, which was described at the time by the NME as “one of the best soundtracks ever, the fact that it has no accompanying movie is a trifling irrelevance.” The album was a calling card announcing Adamson’s distinctive and undeniable talent. He followed this up with another slice of compelling urban-noir brilliance his Mercury Prize-nominated album Soul Murder in 1992.

In 1996 came Oedipus Schmoedipus—one of those albums you must hear before you die—in which Adamson collaborated with Jarvis Cocker (“Set the Controls for the Heart of the Pelvis”), Billy MacKenzie (“Achieved in the Valley of Dolls”) and old pal Nick Cave (“The Sweetest Embrace”). Apart from these gems, there was also the thrilling noirish sounds of “It’s Business as Usual,” “Something Wicked This Way Comes,” “The Big Bamboozle,” and a hat tip to Miles Davis with “Miles.” This led to As Above, So Below in 1998—a masterpiece of jazz or “rock-jazz noir” which offered “a bold, satisfying vision from an artist who shows no fear in expressing the seedier sides of life.”

By the turn of the century, Adamson was producing albums of compelling beauty, originality, and genuine thrills with music as diverse as jazz, funk, soul, rock, lounge and movie soundscapes that unlocked ports of entry to unacknowledged sensations. King of Nothing Hill (2002), the masterwork Stranger on the Sofa (2006), with the ecstatic and rousing single “The Long Way Back Again,” the near perfect “tour-de-force” Back To The Cat (2008), the triumphantly brilliant I Will Set You Free (2012), and the astonishingly great Know Where to Run (2016) which saw Adamson moving in new and untraveled directions.

Adamson has also contributed to the soundtracks of movies by Derek Jarman (The Last of England), Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers and David Lynch’s Lost Highway. In fact Lynch commissioned Adamson after spending ten hours non-stop listening to his albums. He then had him flown out to his studio to work on the film.

And let’s not forget his career as a writer of London noir fiction, his work as film director, producer, and screenwriter and his acclaimed photography which has been published in books and exhibited across the world.

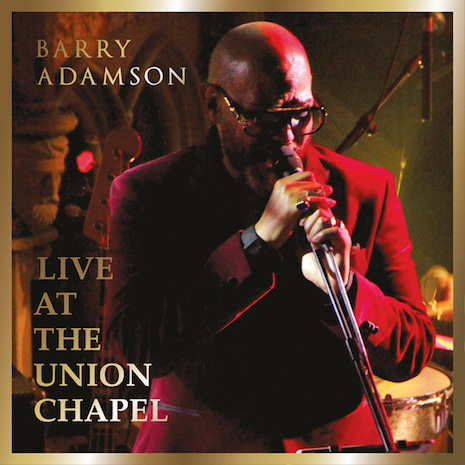

Last year to celebrate his forty years in music, Adamson released a kinda greatest hits Memento Mori which to be frank every home should own a copy of this album. Bringing this altogether, Adamson recorded a concert at the Union Chapel, London, which featured songs from across his whole career including “Split,” (Soul Murder) “Jazz Devil” (As Above So Below), “Sounds From The Big House” (Moss Side Story), “I Got Clothes” (Love Sick Dick), ‘The Hummingbird’ (Memento Mori) and the Magazine classic “The Light Pours Out Of Me.” Last week, I spoke with Adamson over the phone about his new album release, his influences, his early life and career.

Tell me about your new live album.

Barry Adamson: It was recorded at the Union Chapel, Islington, London, I was celebrating a forty year period with an album that had come out Memento Mori and it was decided to record one of the showcases around that record just to make a night of it really.

It’s a bit of closure on the last forty years. Just to have something that was a kind of memento of the whole thing—the forty years and the live experience that had not been actually recorded to date. It’s a first on that level.

It’s also for the people that were there that night and the people that weren’t there that night. For people to hear how this transposes in a live situation. I actually think the record’s really great. There’s some great things going on and it covers such a width and depth of the whole sort of things I’ve been involved in.

You were brought up in Moss Side, Manchester, which was at one point called ‘Gunchester’ because the level of deprivation, crime and violence. What was your childhood like and how did it impact on your first album Moss Side Story?

BA: It was very much a black and white world. I can remember observing everything around me—perhaps that was sort of my personality that was burgeoning at the time—but that would have its own kind of cinematic playfulness to my eye and a kind of mystery element to it as well. I found Moss Side bleak, post-industrial, and very much in a black and white way. But at the same time it was kind of vibrant and thrilling.

By the time I came to do solo work I went back to Moss Side and all the pieces seemed to fit together of something that I had observed but couldn’t articulate in my early years. Then I was able to do something with an album by just looking out the window and opening that window and hearing what was there projected from within myself. I think I was a little bit lost at the time.

What do you mean by ‘lost’?

BA: You know those times when you’ve lost something unique? When you have to come back to yourself and find the things about you that make you you and keep yourself in that way.

I was away a lot working with the Bad Seeds in Berlin. My parents were still in Manchester so I would come back and see them. On the trips back I started to make these cassettes of different ideas and little melodies and sounds. It was almost like time-off, almost like being in the studio and there was time to put something together and make a note of it. It was becoming a thing by itself really.

When I did get back, I took a big breath out. That’s when I decided to move into something that was more about myself. I stumbled upon this idea of a soundtrack that wasn’t necessarily to a movie but just a soundtrack to whatever was going on inside and outside and around me.

I think everybody in their own way goes through a dark night of the soul and I wanted to try and bring it to an end. I think things went a little darker for a while. With hindsight I knew that I was embroiled in a very dark night of the soul and I did also have a kind of resilience that took me back to feeding myself with my own energy and my own art and that’s what I think became a place where I could start the work I was supposed to start anyway. I think looking back over the years it was the right thing to do.

That’s how [Moss Side Story] came about.

Your music is so rich and diverse ranging from the filmic to the funky, rock to jazz, and everything in between, how do you go about composing, coming up with the ideas for your music?

BA: It works in really different ways. It’s like you can be sat around and you can see melodies floating by and your job is to catch them with a butterfly net. You know the ones that have got your name on it because you can recognize them and they’re already sort of formed. Sometimes you sit down and you go “Right, I’m gonna write something today.”

I had a period of about five years after Moss Side Story where I was trying to discipline myself by going into the studio every day and writing something no matter what it was, this little squiggle of notes, just to get into the practice of receiving ideas, working through ideas and becoming an artist. Now I’m very used to the idea it can come at any time and you better write it down, you better make a note of it. I keep notebooks and things to record on all the time and I sit down daily to chisel away like a sculptor until you see a bit of a hand or bit of a knee or a leg. Then you start working away.

Do you find you compose more than you record?

BA: For every album you write two albums. I always do that.

I feel like I have to see every idea out even if I get an inkling it’s not going to work I have to see it out. And really strange things happen, you might have a part that melds itself to something else. I had this happen this week. I put down an idea for something then returned with another idea the following day. Then I played the two ideas and saw they were the same idea as a progression which I didn’t think of before. It’s a bit like sitting there and saying that’s got to go and that’s got to go. The stuff that stays with you, the stuff that taps you on the shoulder you stick with because you know there is something in it and you know you can’t throw it away.

I’m very quick these days, for once I really do know something is out—it’s for the bin, it’s over.

DM Premiere: Barry Adamson - ‘Sounds From The Big House’ from the forthcoming album ‘Live At The Union Chapel.’

Going back to when you started out, what was the inspiration or motivating factor to your joining a band?

BA: Punk rock made it easier to join a band. A couple of years before punk, I’d driven with a bunch of mates to see Led Zeppelin play at Earls Court and watching them I thought how do you get from here [the audience] to there [the stage]? How would you ever be that group? Forget it. But punk made it happen. You’d be propped up at a bar and the guy next to you turned out be Pete Shelley who was having a drink with you and he walks on the stage with this guitar and then starts playing all these brilliant songs. Suddenly punk made it easier to walk from here to there.

How did you go to joining Magazine?

BA: A series of coincidences.

A friend of mine had a bunch of instruments at his place and I’d picked up a bass and he said, “You can have it if you want. I’m not really using it. You can have it.” Then another coincidence was seeing the advert for Howard Devoto’s band and having the balls to call him up and say, “Yeah, I’d like to come around and audition. I’ll be around tomorrow morning.” Then thinking, “Shit. I can’t even play.” [Laughs}

I’d played a little bit of guitar here-and-there. I could play “Smoke on the Water” riff but this bass thing was a whole new thing. When I went around there and he showed me the riff of “The Light Pours Out of Me” it seemed to fit, it all came together. I seem to have a natural aptitude, I don’t know why.

But what made you want to get up on a stage like the guys in Led Zeppelin? What made you want to do it?

BA: It was just this idea of communication and expression. Wanting to express something. Wanting to get whatever it is that makes people want to entertain. Maybe it’s some deep psychological flaw from never being heard as a child and wanting to be heard. [Laughs] I can remember doing all these impressions at school and suddenly I had an audience—I was being listened to. I don’t feel that’s incredibly important to me but somewhere in there there is something about that, there’s something about communication, that whole kind of thing of me being the giver and receiver at the same time. It’s like a life thing.

Music has the power to make people cry, make people laugh. It has the power to do all these things. When you go to a dance and see girls crying and you wonder “What’s going on?” And it’s a song. What? You’re kidding. “I Can’t Live If Living is Without You.” I’ve got to write something like this that brings a connection and all these doors open.

The range of your music is utterly phenomenal, do you think this has perhaps worked against you that people aren’t able to define you by one type of sound?

BA: I think so, yeah. I think in the early days I wanted that, I didn’t want to spoon feed anyone. I wanted people to be challenged. If they got through the first couple of tracks of Moss Side Story or Soul Murder then stuck with it—great. But if they thought What the hell? then fine go and listen to something that is the same over and over.

I don’t see the point of a solo artist writing a song then writing another one that sounds exactly the same then writing another one that is something similar. I can see how that is a very successful method for a band—I’m thinking of like the Foo Fighters but that’s what I want from them I don’t want them to go 3:4 and have a John Barry-esque kind of thing and then come back to something funky.

But yeah, it has worked against me in some ways because you can never pin me down. People don’t like to think you’re being too clever, I guess, I don’t know. But I’m still hoping for a moment when it will all clicks together. One piece is all you need to get through then people will research the other pieces and go, “What? That’s from the same guy. Cool.”

A lot your music has that big epic movie feel, how do you compose for movies, I’m thinking of your work with David Lynch or Danny Boyle?

BA: A movie dictates its own score. It’s up to you to find it. Something that’s in your head isn’t necessarily always right. If I’m doing my own work for my own projects I can go with what’s in my head and work through it. The film dictates what it wants for me and then you bring your knowledge and your experience to the table. How an arrangement would work, how the strings would work, what lines, what counter melodies and all that.

The thing you’re looking for is a tone. That’s the thing you find and you can work around it.

With your own music you’re freer. I’m going to put down a vibraphone, I’m going to but down a choppy guitar. That’s the chiseling away for me. Then you go, “What story am I telling here? How am I going to uplift it? And what can I do there that takes the fucking bomb out if it?” These things are all working at the same time.

I think the melody is really important, something that hooks the ear, even if it’s dissonance. It’s like painting with all the different colors and the tones and the shapes and how all this turns into a feeling. I love that.

*****

If you’ve never listened to Barry Adamson—go buy one of his records now. Or better still buy the new album Barry Adamson—Live at the Union Chapel, which will be released on August 2nd, order your copy here.

Barry Adamson performs Magazine’s ‘The Light Pours Out of Me’—from the forthcoming album ‘Live At The Union Chapel.’

Barry Adamson—‘The Sun And The Sea’—from the forthcoming album ‘Live At The Union Chapel.’