The work of Boston-based visionary artist and architect Paul Laffoley has been exhibited extensively in recent years including major museum shows in London, Paris, Berlin and Seattle. His oeuvre is informed by fringe science, a degree in architecture from Harvard and the occult. In 2009 Laffoley was awarded a Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship for Creative Arts. Next year an extensive catalogue raisonné of his art is set to be published.

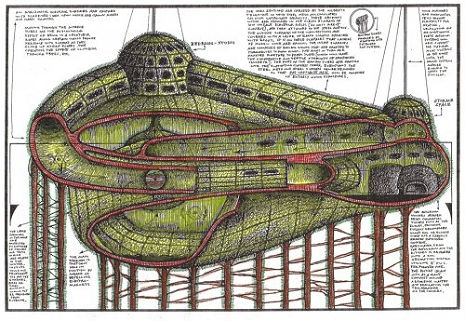

Paul Laffoley’s work can be categorized into several different strands: His architectural pieces which are comparable to schematics or blueprints; his inventions of apparently far out sci-fi devices (keep in mind that every single thing Jules Verne dreamed up eventually came to pass); his plans for a working time machine and for a “living” plant house that would be grown from a single seed.

The artist claims that his “Das Urpflanze Haus” will help solve the worldwide housing crisis.

How did the idea of physically alive architecture first occur to you?

I don’t… I don’t recall… (pauses) I was thinking of how to make a link all the way from Earth to the Moon and I realized that it would have to be something which was self-repairing. Something like that would always be getting hit by asteroids and space debris, so only something alive could self-repair if you were gonna do that. Fixing it would just be too impractical.

Vegetation connects to itself and grafts to its own kind. That’s how vegetables survive, by sending out rhizomes in times of danger and becoming a single plant. The German poet Goethe was fascinated by the idea that there existed an ur-plant that could connect, or graft, all of the plants on Earth together as one big worldwide plant, but he never found it. The name “Das Urpflanze Haus” is a tribute to him. But the primordial plant, something that’s been around since the Jurassic period, is Gingko Biloba—kept alive by monks in their gardens—which has DNA common to every plant living today. The link to the Moon would be constructed from shapes like Buckminster Fuller’s spheres, but they would have to be alive, to be plants. They would have to be grafted together. There would, of course, also have to be a water source.

And then I started thinking that if something like that is going to be built to go to the moon, what could we do on Earth, and that’s where the idea came from. You might use bamboo in some parts of the home, for tensile strength—think of the plants as building materials—and a different kind of plant to thatch the roof, but they would all be joined—grafted together—and have a common root system. After you would make the first vegetable house, it would go to seed and then you could grow more.

Didn’t you run this concept past Buckminster Fuller himself at some point? What was his reaction?

Yes (laughs). It was 1980 and I was a member of the World Future Society. We went to Florence and I did a presentation on this that got absolutely no reaction. I couldn’t sleep and I went down to the hotel lobby and there was Fuller, who couldn’t sleep either and so I presented him with my idea to build a link to the Moon and I asked “Don’t you think this should be a living creature and not a mechanical model?” and he agreed, but eventually I must’ve cured his insomnia because he fell asleep right there in the lobby. The next day he avoided me like the plague!

Has anyone ever really tried to do anything even remotely this?

Well, people bind shrubs together and that kind of thing, but the closest is when they graft one tree onto another tree. I mean, they have, but only to extent that huts and yurts might have trees planted around them and then the branches are braided together, but that doesn’t really allow for an architect to enter the picture.

When houses grown from a single seed become the norm, how will we decorate them?

One very “green” way would be to make Tiffany lamps out of tobacco plants. Scientists have been able to graft luciferin, the genetic material in the tails of fireflies that makes them glow, into tobacco plants. It’s actually easy to do. Now it’s up to biological engineers to increase the wattage, so to speak, from where it’s just glowing until it’s like a 100w bulb that you could read under. Or maybe the plant could be engineered to turn on and off, like the darker it gets outside the brighter the tobacco plant would become inside. That’s not such a big stretch anymore. You would think that “Big Tobacco” would want to get behind this.

It’s the culmination of [Louis Comfort] Tiffany’s vision. He wanted his lamps to look like vegetation and botanicals, so this is perfect. And it represents what I think is the future of architecture and that’s the transition from plant forms made from dead materials—a Roman column is really just a tree, right?—those same forms can be transferred back into living structures. Instead of a column, what about using a living redwood tree?

This post was sponsored by General Snus, the #1 selling snus in the world now available in the U.S.