Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the celebrated author of detective fiction who created the immortal (and highly adaptable) character Sherlock Holmes, was the product of an artistically gifted family. An uncle, the marvelously-named Dicky Doyle, became quite famous as an illustrator during a noteworthy tenure at Punch. Other uncles James and Henry Doyle were also artists of some repute.

And then there was his father, Charles Altamont Doyle. Charles was also an artist, but he achieved no prominence in his lifetime. He was employed as a civil servant in Edinburgh, an assistant surveyor in the Scottish Office of Works. Though as a young man he was cheerful and curious, he retired at the improbable age of 46, suffering from headaches, alcoholism and depression. He spent the last dozen years of his life involuntarily committed to various asylums, and his 1893 death certificate lists his cause of death as epilepsy.

But during his period of commitment, Doyle père continued to make art, and even illustrated for his son an 1888 edition of A Study in Scarlet, the very first Sherlock Holmes story. But the depth of Charles’ talent only really emerged decades after his death, in the most improbable of ways:

Doyle’s book came to light in early 1977. It belonged to an Englishwoman who had been given it more than twenty years before by a friend who had in turn bought it in a job lot of books at a house sale in New Forest. This was probably Bignell House, Conan Doyle’s country retreat near Minstead, which was sold by the Doyle family in 1955. For years the book lay undisturbed, stored with other items in a children’s playroom.But finally, on the recommendation of a painter friend, its owner approached the Maas Gallery with it. The Maas Gallery, one of the leading dealers in Victorian art in London, quickly realized that the Doyle book was a major find. Richard or “Dicky” Doyle, Charles’ brother, had long been familiar to art historians as a talented and successful Victorian illustrator, but only in the previous ten years had there been any awareness of Charles—and even then only through rare original works. Here, however, was evidence for the first time of a more systematic output which, in its scope and originality, entitled Charles to artistic status in his own right.

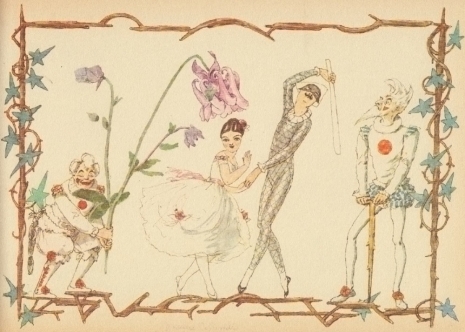

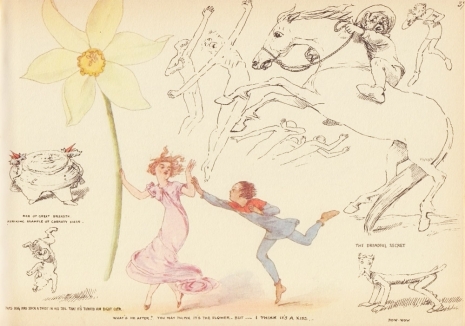

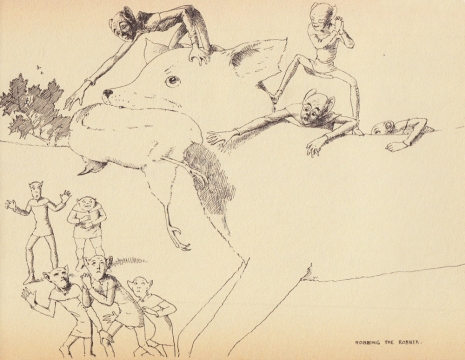

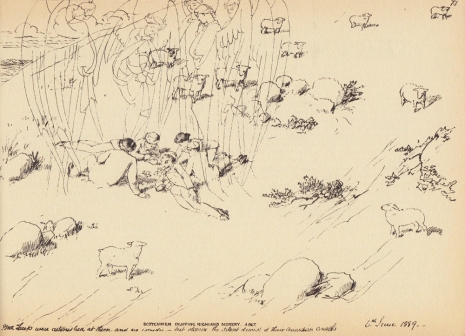

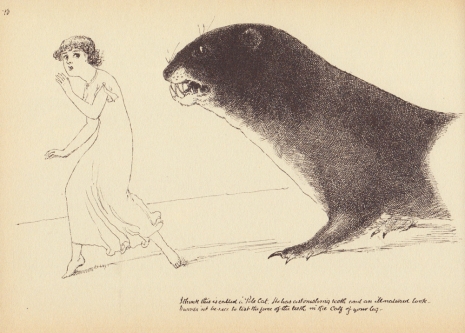

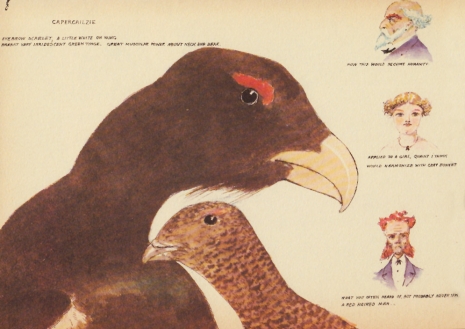

The foregoing comes from Michael Baker’s exhaustively researched biography of Charles Altamont Doyle, which served as the introduction to his lovely book The Doyle Diary, which reproduced the unearthed sketchbook/journal. Doyle’s drawings reproduced therein reveal a melancholic soul—hardly surprising as all the works are dated during his lengthy confinement—with a naturalist’s flair for rendering birds and flora, plus an interest in the Victorian vogue for fairies. It’s a volume of escapist work, heavy on spiritualist and fantasy themes, and it opens with the inscription “Keep steadily in view that this Book is ascribed wholly to the produce of a MADMAN. Whereabouts would you say was the deficiency of Intellect? Or depraved taste? If in the whole Book you can find a single evidence of either, mark it and record it against me.” Doyle clearly bristled strongly against his internment, and found in art an escape.

The Doyle Diary, published in 1978, is long out of print, though curiously, someone seems to believe there’s a demand for housewares emblazoned with Doyle’s fairy paintings. We’ve selected some favorite sketchbook images to show you. Clicking an image spawns an enlargement.

Previously on Dangerous Minds:

Sherlock Holmes recreated as police composite sketch