The other evening round at DM Towers, Glasgow, as I lay reclining on the chaise longue in my plus fours, smoking jacket, and fez, quietly puffing on my Meerschaum and idly fingering Roget’s Thesaurus, an unholy apparition appeared at the library door. It was my girlfriend. Yet, I would never have recognized her, as her whole countenance had vanished into a grotesque black hole from hairline to chin.

“What infernal magic is this?” quoth I (we do a lot of quothing round our house) in my best quivering voice from behind the chaise longue.

“Why it is only I,” rejoined my girlfriend.

And it was. But that face—what had happened to it?

As it, fortunately, turned out, my dearest was merely sporting an antique item of fashion called a vizard. That is a type of mask once worn by posh birds to avoid unsightly contact with the sun which could result in the unfortunate bronzing of the skin and the worrisome fear of being considered a lowly working-class woman who spent her days toiling in fields under the sun. (“Tanning” wasn’t considered a “thing” until beach vacations were invented for rich people.)

This was all rather serendipitous in a way, as I had, only that morning, been reading young Master Pepys’ diary about his visit to the Royal Theater where he had chanced upon Lord Falconbridge and Lady Mary Cromwell. As the public began to fill the house, Lady Cromwell “put on her vizard, and so kept it on all the play”. Pepys said the vizard had “become a great fashion among the ladies, which hides their whole face.” Meeting the fashionable Lady Cornwell encouraged Pepys to go to “the Exchange, to buy things with my wife; among others, a vizard for herself.”

Intrigued by my fair lady’s latest fashionable accessory, I decided to find some fine examples of the vizard from history with which to share. It would seem, the vizard was once very popular in England during the late 16th and most of the 17th centuries, roughly from the reign of Queen Elizabeth I to the Restoration. They were worn as sun protectors, and on occasion to keep a woman’s face wrapped from the biting chill of a winter’s wind. They were also a means to create coquettish mystery—just as the Venetians wore masks to flirt with each other. The vizard was large, spherical in shape, with a black velvet exterior and a silk lining. There was a small rectangular niche for the nose and two small oval openings for the eyes. The mask was held in by the wearer’s teeth, as it is described in The Academie of Armorie (1688):

A mask [is] a thing that in former times Gentlewomen used to put over their Faces when they travel to keep them from Sun burning… the Visard Mask, which covers the whole face, having holes for the eyes, a case for the nose, and a slit for the mouth, and to speak through; this kind of Mask is taken off and put in a moment of time, being only held in the Teeth by means of a round bead fastened on the inside over against the mouth.

Not everyone was so taken with the latest fashion, the writer Phillip Stubbes wrote in Anatomy of Abuses (1583):

When [women] use to ride abroad, they have visors made of velvet… wherewith they cover all their faces, having holes made in them against their eyes, whereout they look so that if a man that knew not their guise before, should chance to meet one of them he would think he met a monster or a devil: for face he can see none, but two broad holes against her eyes, with glasses in them.

The playwright John Dryden was similarly droll in the prolog to one of his lesser-known plays, The Conquest of Granada by the Spaniards:

[W]hen Vizard Masque appears in Pit,

Straight every Man who thinks himself a Wit

Perks up; and, managing his Comb with grace,

With his white Wigg sets off his Nut-brown Face;

That done, bears up to th’ prize, and views each Limb,

To know her by her Rigging and her Trimm;

Then, the whole noise of Fops to wagers go,

Pox on her, ’t must be she; and Damm’ee no:

The vizard was fashionable among the higher classes until around early 1700s, when it became the preferred disguise for prostitutes to sell their wares.

‘A horseman with his wife in the saddle behind him’ circa 1581.

Pietro Longhi, ‘Rhinoceros,’ 1751.

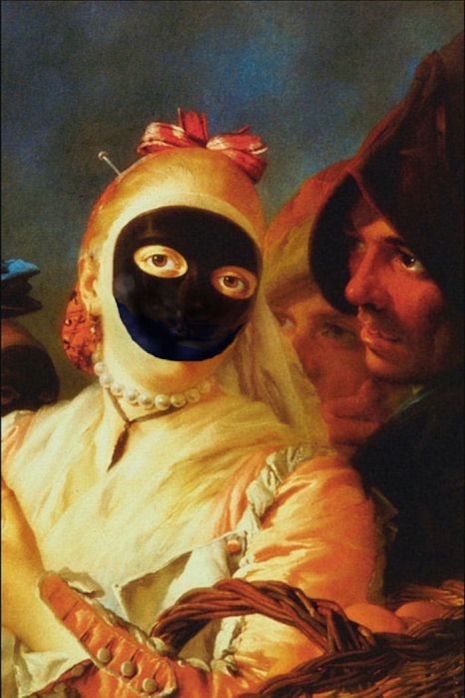

Felice Boscarati ‘Lady in a Mask’.

Postcard of Boscarati’s ‘Woman in a Mask.’

Hollar’s ‘The Winter Habit of an English Gentle Woman.’

Hollar’s ‘A fashionable Lady in Winter.’

‘A woman wearing a visard,’ as engraved by Abraham de Bruyn in 1581.

This is a vizard found in the wall of a 16th-century house in Daventry, England.

Previously on Dangerous Minds:

Beautiful handmade Venetian carnival masks

‘Happy happy joy joy!’: Hyper-realistic Ren & Stimpy masks

‘One of Us:’ Stunning portraits of origami masks

Creepy Dental Surgical Masks