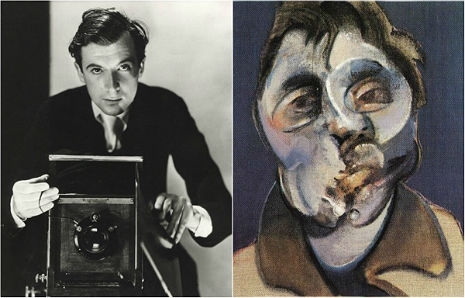

“Selfies” by Cecil Beaton and Francis Bacon

When I was young, I always enjoyed reading tales of the meetings between artists and writers and the creative impact their association brought. Whether Van Gogh and Gauguin, Morecambe and Wise or Kerouac and Burroughs. It inspired me to imagine my own speculative tales of fruitful encounters that mixed fact and fiction. One involved Sherlock Holmes returning from his final encounter with Moriarty at the Reichenbach Falls and making his way across Europe to Paris, where he chanced upon the exiled Oscar Wilde. I decided the two would team-up to investigate a series a bloody murders carried out across the city by none-other-than Jack (perhaps now Jacques?) the Ripper, who had escaped to the city from London. It could make an interesting book, the involvement of a fictional detective used as a cypher to give a biography of Wilde’s final days together with an investigation into the possible identity of the Ripper.

But one hardly has to look far for such inspirations—a three-act play could be written from the meetings between the celebrated photographer, designer and diarist Cecil Beaton and artist Francis Bacon.

In the late 1950s, Beaton asked Bacon to paint his portrait. He had liked his painting of Sainsbury, the art collector, and had always found the artist “most interesting, refreshing and utterly beguiling”.

Beaton had been good friends with Bacon for some time, first hearing of him through their mutual acquaintance, artist Graham Sutherland, who said:

‘[Bacon] seems to have a very special sense of luxury. When you go to him for a meal, it is unlike anyone else’s. It is all very casual and vague; there is no timetable; but the food is wonderful. He produces an enormous slab of the best possible Gruyère cheese covered with dewdrops, and then a vast bunch of grapes appears.’

Beaton described his first meeting with Bacon in his diary:

When I met Francis we seemed to have an immediate rapport. I was overwhelmed by his tremendous charm and understanding. Smiling and painting simultaneously, he seemed to be having such a good time. He appeared extraordinarily healthy and cherubic, apple-shiny cheeks, and the protruding lips were lubricated with an unusual amount of saliva. His hair was bleached by sun and other aids. His figure was incredibly lithe for a person of his age and occupation, wonderfully muscular and solid. I was impressed with his ‘principal boy’ legs, tightly encased in black jeans with high boots. Not a pound of extra flesh anywhere.

Of all the qualities Beaton most admired about Bacon it was his independence he liked best, “being able to live in exactly the way he wished.” He was also impressed by the artist’s “aloofness from the opinion of others.”

An arrangement was made for Bacon to paint Beaton’s portrait in 1959, at his London studio in Overstrand Mansions, Prince of Wales Drive, Battersea.

Francis started to work with great zest, excitedly running backwards and forwards to the canvas with gazelle-springing leaps—much toe bouncing. He said he how enthusiastic he was at the prospect of the portrait which he said would show me with my face in tones of pink and white. He did not seem interested in my keeping still, and so I enjoyed looking around me at the incredible mess of his studio—a converted bedroom no doubt: so unlike the beautiful, rather conventional ‘artist’s abode’ that he worked in in South Kensington when I first knew him! Here the floor was littered in a Dostoevsky shambles of discarded paints, rags, newspapers and every sort of rubbish, while the walls and window curtains were covered with streaks of black and emerald green paint.

Francis was funny in many ways, slightly wicked about pretentious friends, and his company gave me pleasure. The only slight anxiety I felt was that there might be some snag which would interrupt the sittings that were to follow. Sure enough, a telegram arrived putting me off the next appointment; indeed, for anyone less tenacious than myself, there would never have been another sitting.

Time passed, but no further mention was made of the portrait, until Beaton found an opportunity to ask Bacon “if he’d hate to go on with the painting?” A new date was settled for a return to the studio, where Beaton was placed in a kitchen chair and told to turn his his head this way, further, further, ah, yes, that’s it.

Francis started to work with energy, but he seemed to look harassed, not at all happy. I asked: ‘Would you prefer if I looked more this way?’ ‘No—it’s fine—and I think if it comes off, I’ll be able to do it quickly. The other [portrait] didn’t start off well—but this is fine.’ Would I mind his exhibiting the canvas as the Marlborough [Bacon’s dealers] were screaming at him for more pictures?

Bacon was recovering from having a tempestuous time in Tangiers, where his lover had badly beaten him, knocking out one of his teeth, “My face is an appalling mess,” he said.

Occasionally Francis would sit down on a old chair from which the entrails were hanging and which had been temporarily covered with a few French magazines and newspapers. His pose reminded me of a portrait of Degas. He curved his head sideways and looked at his canvas with a beautiful expression in his eyes. His plump, marble-like hands were covered with blue-green paint. He said he thought painting portraits was the most interesting thing he could ever hope to do: ‘If only I can do them! The important thing is to put the person down as he appears to your mind’s eye. The person must be there so that you can check up on reality—but not be lead by it, not be its slave. To get the essence without being positive about the factual shapes—that’s the difficulty. It’s so difficult that it’s almost impossible! But that’s what I’m trying to do. I think I’m closer to it than I have ever been before.’

Bacon was becoming “even more renowned” and there was an incredible demand for his work. The sittings continued, until at last one day Bacon stopped, cocked his head, looked at the portrait and said, “I’m very pleased with this portrait. I think it’s going to be all right: one of the best things I’ve done. Next time you’re here, I’ll show it to you because it doesn’t need much more work on it. When they go well, they go very quickly.”

Francis opened the door, smiled and said: ‘The portrait’s finished! I want you to sit in that chair over there and look at it.’ I walked towards Francis’s degutted chair in the corner, not glancing at the canvas on the way. I turned round square and sat to get the full effect. It was as well that I was sitting, otherwise I might have fallen backwards. In front of me was an enormous, coloured strip-cartoon of a completely bald, dreadfully aged—nay senile—businessman. The face was hardly recognizable as a face for it was disintegrating before your eyes, suffering from a severe case of elephantiasis: a swollen mass of raw meat and fatty tissues. The nose spread in many directions like a polyp but sagged finally over one cheek. The mouth looked like a painful boil about to burst. He wore a very sketchily dabbed-in suit of lavender blue. The hands were clasped and consisted of emerald green scratches that resembled claws. The dry painting of the body and hands was completely different from that of the wet, soggy head. The white background was thickly painted with a house painter’s brush. It was dragged round the outer surfaces without any intention of cleaning up the shapes. The head and shoulders were outlined in streaky wet slime.

Francis expected that I would be shocked. He was a little disconcerted. He said it gave him a certain pain to show it to me, but if I didn’t like it I needn’t buy it. The Marlborough Gallery would want it. I stammered: ‘Well—I can’t say what I think of it. It’s so utterly different from anything of yours I’ve ever seen!’

Beaton thought the picture was “of an unusual violence” painted in a manner that broke all the rules. Sensing Beaton’s horror, Bacon was typically gallant and charming offering his friend to take it and if he didn’t like to send it back. Beaton was baffled at the offer, then asked if he bought it could he sell it again? “Of course!” Bacon replied, “It’s yours to do what you want with.”

Beaton returned home “crushed, staggered and feeling quite a great sense of loss.” No sooner had he written these very words in his diary, the telephone rang.

It was Francis. In an ecstatic voice he said:

‘This is Francis, and I’ve just destroyed your portrait.’

‘But why? You said you liked it? You thought it such a good work, and that’s all that matters!’

‘No—I don’t like my friends to have something of mine they don’t like. And I often destroy my work in any case; in fact, I’ve destroyed most of the pictures for the Marlborough. Only I just wanted to let you know so that you needn’t pay me.’It seemed little to Francis to waste all that work. He seemed jubilant at not getting paid, at not finishing a picture. He said that perhaps, one day he’d start again, or do one from memory: ‘They often turn out the best,’ he said.

Bacon’s portrait may (sadly) no longer exist, but in 1971 a photographer directed a documentary on Cecil Beaton for ATV, which due to having its embedding disabled, can be only seen here. However, another meeting of talent, when Cecil Beaton photographed (one of his favorite sitters) Marilyn Monroe, can be seen below.