Georgia O’Keeffe was going to give up painting ‘cause she couldn’t stand the smell of turpentine. She started teaching instead and doing commercial art and making charcoal drawings that she occasionally showed to friends. In January 1916, one friend passed a bunch of these drawings on to photographer Alfred Stieglitz who thought they were the best things he’d seen. Stieglitz included O’Keeffe’s work in an exhibition at his 291 Gallery in New York. O’Keeffe knew nothing about it until the show was opened and the reviews were in. The reviews were great. O’Keeffe turned up at the gallery to tell Stieglitz off. It was the start of a relationship that lasted thirty years until Stieglitz’s death in 1946.

Stieglitz was a pioneer of photography. He has been described as “perhaps the most important figure in the history of visual arts in America,” which is one helluva reputation. He described taking photographs as a method of seeing straight. It was a way to create “a reality so subtle that it becomes more real than reality.” His body of work includes some 2,500 mounted photographs. These, of course, are only the photographs he wanted to be seen. His photographs tended to be artfully constructed and the product of multiple takes. He was a control freak. He was also a hypochondriac.

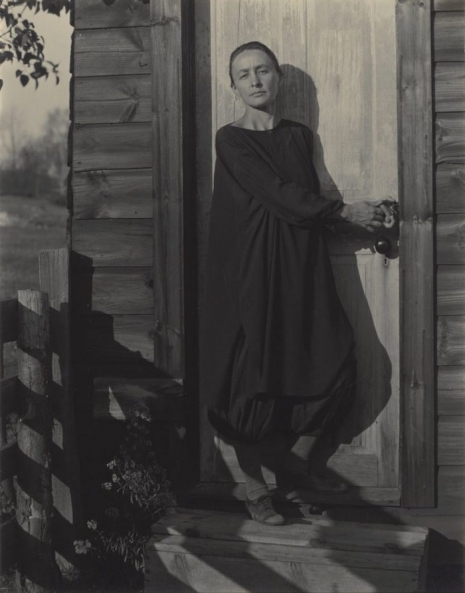

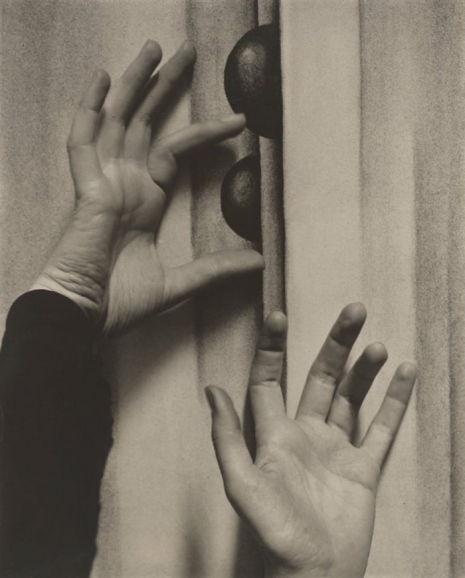

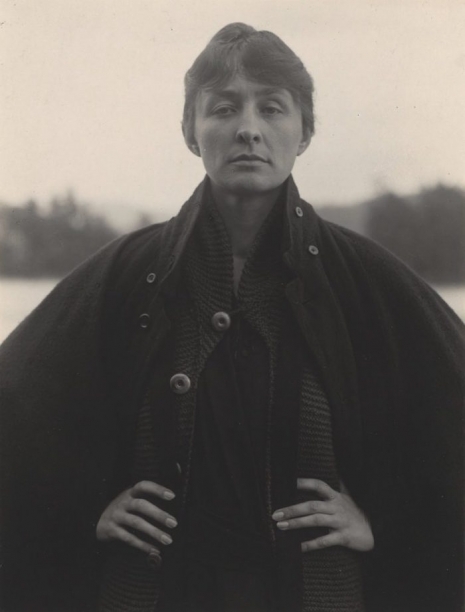

Old Stieglitz was a 52-year-old married man with a family when he first met young 29-year-old O’Keeffe. She was smitten by another, which made Stieglitz more determined to win her over. He organized an apartment for O’Keeffe to live and work in and paid the rent. He started taking photographs of the young artist. He took pictures of O’Keeffe at work, outside her studio, in close-up, her hands at play, throughout her strong natural iconic beauty. By the 1920s, O’Keeffe was the most recognizable female artist in America. Stieglitz also shot a series of seemingly “intimate” photographs of a naked O’Keeffe which he exhibited in 1921.

These photographs were considered shocking and deeply intimate but they were actually carefully staged and the result of dozens of shots. O’Keeffe said she posed for hours to get the image Stieglitz wanted. These pictures suggested the pair were having an affair. O’Keeffe was apparently mortified that anyone should ever think she was the photographer’s mistress.

Eventually, Stieglitz’s wife caught the pair together. A divorce followed. O’Keeffe and Stieglitz married. Soon, O’Keeffe found Stieglitz’s demands for her time and energy left little for own life and career. She quit New York. Moved to New Mexico and set up her own studio. O’Keeffe spent around six months a year doing her thing. Other lovers came and went. Paintings and photographs were produced, but still, the pair remained married, and O’Keeffe was always ready to be photographed by her husband.