This is the third and final installation of posts from the influential graphic artist Art Chantry’s forthcoming book Art Chantry Speaks: A Heretic’s History of 20th Century Graphic Design. The first is here, the second here. Chantry’s clear reverence for and deep knowledge of the history of his discipline, particularly in championing its seediest manifestations and its obsolete processes, informs a body of work which as much as anyone’s has been THE look of garage punk and grunge, and we’re grateful to Chantry and Feral House for letting us use his work in this form. —Ron Kretsch

We’re all familiar with stock photos. Nowadays, most professional photographers I know no longer take photos, but make stock images. These photos are sold through websites for download and reproduction. Designers grab these photos, sometimes actually paying for them, and then “re-work” them in Photoshop to create the desired image. Basically they take stock photos and make new photos out of them. Strange days.

Maybe not so strange. This system existed back in the earlier days of advertising and design as well. The images were often seconds, outtakes and highly adaptable images that could be used in any of a number of settings and advertising situations. The user would order it through the stock photo house (often out of a printed catalog). Then the stock house would send them either a slide or a print of whatever was needed for their use. The user would pay a “usage fee” depending on how the photo would be used. If it was to be used in a dummy or comp, the fee would be much smaller than if it were to be used in a brochure printed in the millions of copies and distributed worldwide. Very practical, and everybody made money. It would still cost much less than hiring a “live” photographer and working with them to obtain the custom photo image you might need.

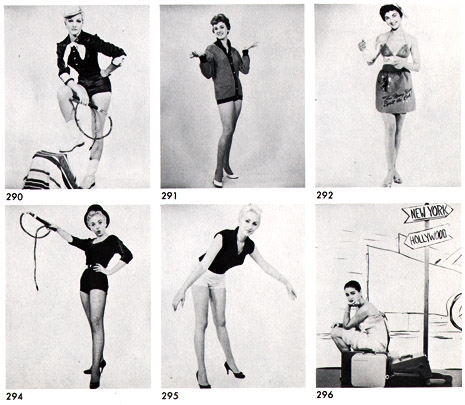

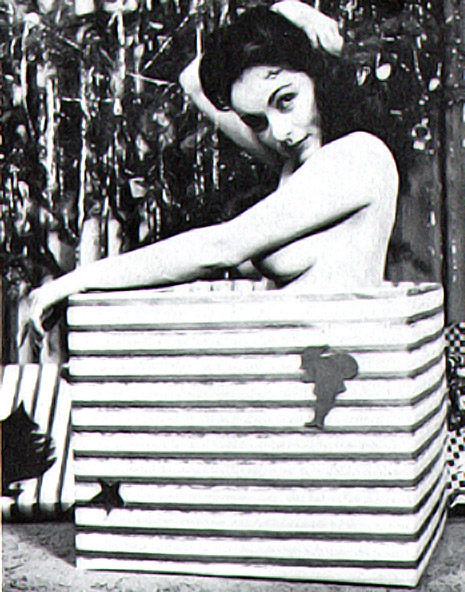

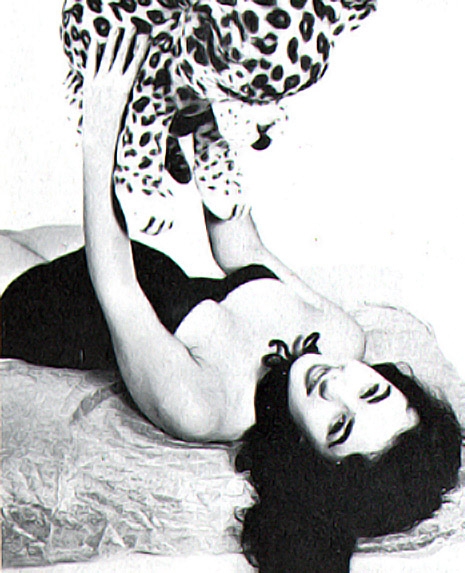

In the postwar period—the glory years of “Mad Men”-style advertising—one of the most popular forms of stock photography was the “glamour” shot. This was an offshoot of model photography that would have a buxom, beautiful young woman posing in a variety of peculiar environments (and varying states of dress) that could be used for adverts or calendars or even be picked up by “men’s magazines” and used to entice America’s hormone-soaked males.

A lot of these glamour stock photo companies were little more than a single somewhat slippery fella with a studio, camera equipment and a lot of props. I think of this territory as classic “bachelor pad” photography—that weird fetishistic territory where the hot-shot handsome young man with a camera used the existing system to meet hot chicks and maybe get lucky. Then they would make some money on the side. It’s one small step above pornography. Indeed, back in the days of our fathers, this was viewed as “R-rated” pornography. Those old “morality code” systems disappeared in the late ‘60s and are almost forgotten.

Once in a while I’ll get lucky and find an old catalog of glamour photography stock photos. Some of the glamour photographers became quite famous, like Russ Meyer and Peter Gowland and even Bunny Yeager. Exactly what kind of advertising could this stuff be used for? Dunno. They all have terms and conditions of use on the cover and the rest of the catalog is only photos of buxom scantily clad babes in silly poses. I swear I’ve seen some of these images in old “men’s magazines” of the ‘50s and ‘60s with names like Cocktail and Duke.

Art Chantry is a graphic designer with more awards and accolades than he can shake a stick at, including a Golden Lionne from Cannes. Over his 40-year career, he worked on the dark side of the marketing world, concentrating on popular culture and broken clients. during that time he managed to brand a cultural moment in time - grunge. His works hangs in the Smithsonian, MoMA, the Library of Congress, the Louvre, and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. More recently, he’s been getting old and writing down his heretical notions about the work he immersed himself in. The results weren’t pretty. Art Chantry Speaks: A Heretic’s History of 20th Century Graphic Design is due out on July 14th.