During the 1960s Ken Russell flourished as a director of television documentaries for the BBC. Single-handedly he advanced the genre, creating a hybrid form of drama-documentary—the biopic. This was first seen in his remarkable film on Elgar in 1962—which was later voted the best single documentary of the decade. In collaboration with a young Melvyn Bragg—who acted as screenwriter—he produced The Debussy Film starring Oliver Reed in 1965—which is arguably the single most influential drama-doc of the past 50 years as it reinvented the drama doc as a film within a film—a template later copied,developed and stolen from by innumerable filmmakers. Then came the the understated film on Delius Song of Summer in 1968, before finally and most controversially making his farewell film for the BBC Dance of the Seven Veils A Comic Strip in Seven Episodes on the life of Richard Strauss 1864-1949. Russell’s film infamously depicted the German composer of “Also Sprach Zarathustra” as a Nazi, which outraged critics, lead to questions being raised in the British Parliament, and was eventually banned.

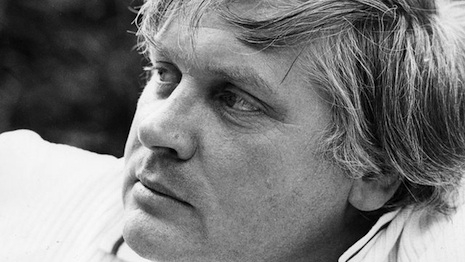

A young Ken Russell on the balcony of his apartment in Bayswater, late 1959s.

Russell’s visually brilliant and intuitive style of film-making was a long way from the kind of straight documentaries made by his contemporaries—including John Schlesinger, whom he had replaced at the BBC. Then ‘biography’, as Joseph Lanza explained in Phallic Frenzy: Ken Russell and His Films, was:

...more like strict documentary. There was no place for metaphors or speculative drama. The network’s purists felt such tactics were synonymous with the kinds of exaggeration [the Futurist artist] Henri Gaudier championed and that Russell longed to create. So Russell kept a humble exterior while secretly plotting to subvert the BBC’s codes of propriety.

“Ken was different in every way from what he is now,” Russell’s BBC boss Huw Wheldon reflected in the early 1970s on working with Russell in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s. “To start with, he was virtually wordless. He was shy and quiet. Quiet in every way: his clothes, his haircut, his countenance. A little watchful, but silent and completely modest. I couldn’t make head nor tail of him, partly because he wouldn’t help me. He didn’t say anything. He just looked at me.”

Russell’s first short film for the BBC’s Monitor series was Poet’s London - an effective evocation of John Betjeman’s poetry. This was quickly followed by Guitar Crazy on the rise of guitar music; Portrait of a Goon, a look acclaimed comic and scriptwriter, Spike Milligan; and a profile of dance legend, Marie Rambert and her ballet company. Then in 1960, during a summer break from the series, Russell wrote, directed and produced his first full-length documentary film, A House in Bayswater.

A scene from ‘A House in Bayswater.’

In An Appalling Talent - Ken Russell, film writer and critic, John Baxter described Russell’s film as ‘...ostensibly a protest at the razing of tall old buildings to make way for office blocks…’

‘Beginning as a systematic representation of Bayswater as a hive of creative activity - his chosen terrace houses a painter, a photographer, a ballet dancer and ex-pupil of Pavlova, a retired lady’s maid who pines for the affluent USA of the Twenties, and an odd but lively landlady - the film changes tone as both artists reveal themselves as tedious poseurs, and Russell’s sympathy swings towards the old people, sustained and enriched by the past. The dancer, leading her willing, wispy pupil through a two-woman show hazed in memoriesof better days (“My next solo is one I did on Broadway in 1929 and I am wearing the same costume”) is faded but not absurd, the maid’s images of New York have the insouciant fever of Scott Fitzgerald, and the concierge who sells her junk to the photographer for props, offers bumpers of sherry as rent receipts and cultivates toadstools and deadly nightshade in the garden with a philosophical “They might come in useful” celebrates the indestructible eccentric. The last Cocteauesque image, of the dancer and her little pupil battling in slow motion against a windy torrent of streamers and balloons (to be recalled in the 1812 episode of The Music Lovers) holds the promise of immortality for all those who survive and, above all, keep faith.’

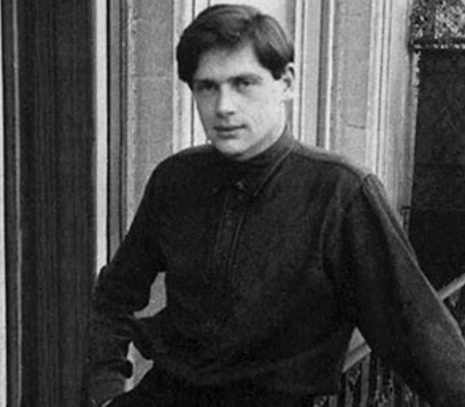

Russell at the Steenbeck with legendary BBC producer Huw Wheldon looking over his shoulder.

A House in Bayswater is a beautiful piece of documentary-making, which slowly develops towards a memorable finish. What isn’t revealed is that the fact this was this house in Bayswater was Ken Russell’s home during the 1950s.

I have lived most of my life in rooming houses, and shared apartments, and run-down hotels, where there is great comfort in anonymity and company amongst strangers, and understand Russell’s nostalgia for a life that is being slowly removed, as cities are carelessly gentrified. Watching it in the month when New York’s Chelsea Hotel announced its demise, only reinforced how much of our shared environment is now monetized for the benefit of a few. This is apparent in Russell’s film, as the film details the lives and hopes of the tenants, connected by a house that was planned for demolition—to be replaced “by a soulless office block. Thankfully, this never happened and the house stands to this day.”

Previously on Dangerous Minds

The Book, The Sculptor, His Life & Ken Russell

Ken Russell’s banned film: ‘Dance of the Seven Veils’