So, this is Christmas and…no matter what you’ve done, may I wish you all the very best Compliments of the Season, Happy Holidays and a very Merry Christmas.

Ah, Christmas. This magical pagan-Christian festival which owes as much to the Victorians and Charles Dickens for the way it is celebrated as it does to good ole Jesus and a bunch of Druids. In many respects it’s fair to say, Dickens was the man who revitalized (or some might say reinvented) Christmas with his classic tale A Christmas Carol. Dickens became so associated with Christmas that when he died in 1870, there was a suggestion that if Dickens could die then so could Father Christmas. But his inspiration was not religious or even superstitious but rather his book was written as a response to the grim inequalities of Victorian England.

Originally, Dickens considered writing a political pamphlet to highlight the issue—An Appeal to the People of England, on behalf of the Poor Man’s Child—but figured such a pamphlet would have only a very limited appeal to well-meaning academics, enthusiastic charity workers, liberal politicians and rich philanthropists.

It was after he addressed a political rally in Manchester, in October 1843, where he encouraged workers and employers to join together in order to bring about social change, that Dickens decided it would be far, far better to write a story that would carry his message to the greatest number of people.

He reworked a story he had previously written in The Pickwick Papers—”The Story of the Goblins who Stole a Sexton” as the basis for A Christmas Carol. He wrote it in a furious burst of creative energy in between completing chapters for his serialized novel Martin Chuzzlewit. His story of an old miser called Ebenezer Scrooge being given a chance of redemption through the visits of three ghosts was his response to the horrific working conditions Dickens had seen in London and Manchester. During the writing of the A Christmas Carol, he would often wander out at night around the grim and impoverished London boroughs, sometimes making a loop of ten-fifteen miles in a night, witnessing firsthand the extreme poverty endured by working class families—in particular their children.

Published on December 17, 1843, A Christmas Carol sold 5,000 copies by Christmas Eve. Dickens believed this book was the greatest success he ever achieved, becoming his best-known book which has never been out-of-print since its first publication.

A Christmas Carol isn’t really a traditional ghost story of the kind later made famous by M. R. James or Algernon Blackwood. The real horror of the story is not the ghosts but rather the horrors of Ignorance and Want hiding in the cloak the Ghost of Christmas Present:

They are Man’s and they cling to me, appealing from their fathers. This boy is Ignorance and this girl is Want. Beware them both, and all of their degree, but most of all beware this boy for on his brow I see that written which is Doom, unless the writing be erased.

While the emotional (or rather sentimental) heart of the tale rests with Bob Cratchit and the fate of Tiny Tim. Moreover, as G. K. Chesterton pointed out though Dickens considered himself “to be a brisk man of the manufacturing age, almost a Utilitarian,” he defended the medieval feast of Christmas (food, alcohol, and dancing) “which was going out against the Utilitarianism which was coming in. He could see what was bad in medievalism. But he fought for all that was good in it.”

The story has inspired numerous movies (the one with Alastair Sim being a personal favorite), musicals (yep, I dig Leslie Bricusse score for Scrooge), comedies, and of course radio and TV versions—most recently a “woke” interpretation starring Guy Pearce as Ebenezer.

In 1971, the brilliant, nay genius animator Richard Williams made his version of A Christmas Carol starring Alastair Sim as Scrooge, Michael Hordern as Marley, Melvyn Hayes as Bob Cratchit, Joan Sims as Mrs Cratchit and Michael Redgrave as the narrator.

Williams, who died earlier this year, was one of the most innovative and original animators of the past sixty years. His work ranged from his award-winning debut animation The Little Island to the titles for What’s New Pussycat? and A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum to the animation for Who Framed Roger Rabbit and his great magnum opus which was wrestled from his hands by philistine producers The Thief and the Cobbler.

A Christmas Carol was first broadcast on U.S. television by ABC on December 21, 1971, and released in cinemas the following year. The film deservedly won Williams an Academy Award for Best Short Animation. It’s magical, beautiful film, which is suitable for getting in the mood for today.

Warmest wishes to { feuilleton }.

Previously on Dangerous Minds:

A Classic Ghost Story for Christmas: ‘Whistle and I’ll Come to You’

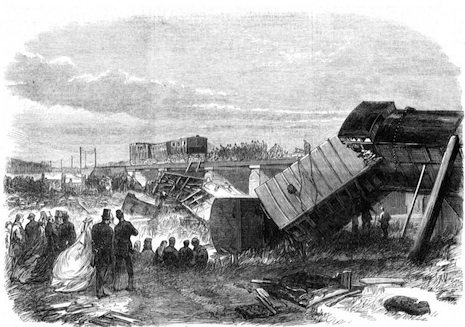

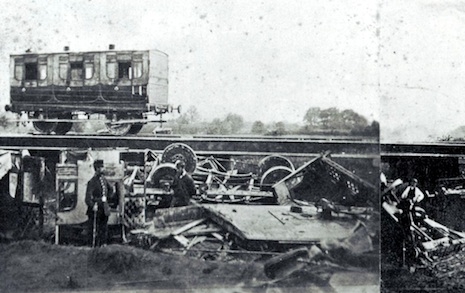

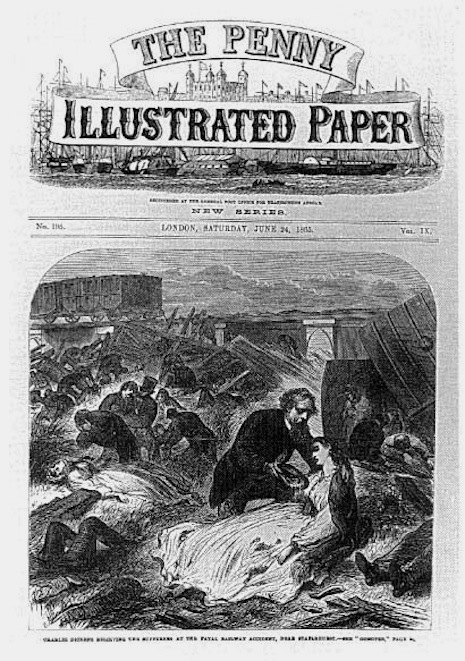

Charles Dickens & The Train of Death: The rail crash behind the classic ghost story ‘The Signal-Man’