In February 1957, Orson Welles walked onto to Stage 19 at Universal Studios to begin directing his first Hollywood movie in almost a decade—Touch of Evil. The studios thought Welles was a risk—he was considered difficult, troublesome, a bad boy who just wouldn’t do what the studio execs told him to do. His last Hollywood feature had been the low budget Macbeth for Republic Pictures—a company better known for producing two-reeler westerns. At first Republic were keen on big old Orson bringing some high-falutin’ literary class to their stable, but after seeing the final cut, they took fright and delayed the film’s release for over a year.

Having his work held back or re-cut or burnt, encased in concrete and dumped in the sea—as happened to footage from his second movie The Magnificent Ambersons—was fast becoming the Hollywood norm for Orson Welles.

If Universal considered hiring him a risk—then it was a far greater risk for the writer, director and star to put his trust back with the studios—because no matter what he did or didn’t do, it was fairly easy money to bet that the no-neck Hollywood execs would royally fuck it up once again. And that, dear reader, is exactly what they did do.

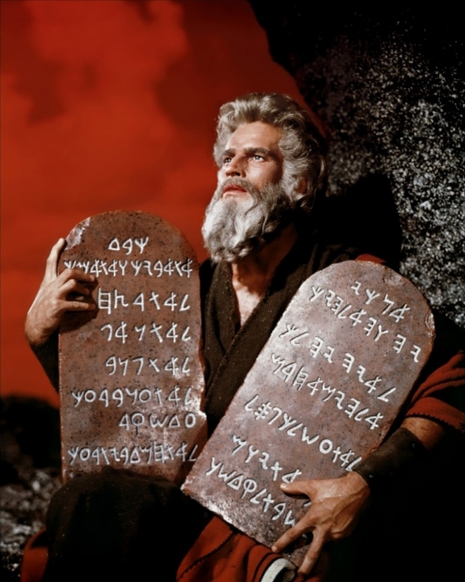

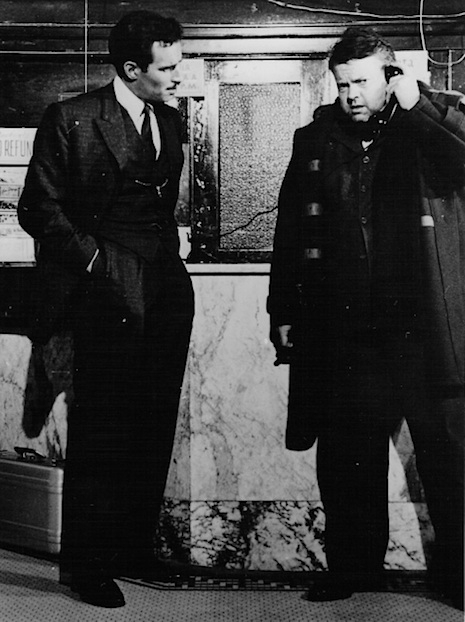

Bad cop, good cop: Welles as corrupt police captain Hank Quinlan and Charlton Heston as Mexican drug enforcement official Miguel “Mike” Vargas.

There are different stories as to how Welles ended up directing Touch of Evil, a low-budget film noir of murder and corruption in a small border town. One goes something like this: lead actor Charlton Heston suggested Welles as director—which is a probable—only agreeing to star once Welles was signed-up to direct and appear in the film. As Universal wanted Heston—they were only too happy to oblige.

The other has Welles pitching ideas and looking for a script or a book or a story so bad, so obviously unfilmable that only a genius of Welles’ waist size could make it work.

Welles took one look at the screenplay based on a cheap pulp novel by Whit Masterson—the pen name of writing duo Bob Wade and Bill Miller—and decided he’d found his movie. Unlike say Alfred Hitchcock who always had his films worked out shot for shot long before a camera turned over, Welles wrote and rewrote the script throughout filming—often improvising and collaborating with the actors on dialogue. Welles also took the unusual approach of rehearsing the script with the cast prior to filming. Actress Janet Leigh—who played Heston’s wife in the film—later recalled:

We rehearsed two weeks prior to shooting, which was unusual. We rewrote most of the dialogue, all of us, which was also unusual, and Mr. Welles always wanted our input. It was a collective effort, and there was such a surge of participation, of creativity, of energy. You could feel the pulse growing as we rehearsed. You felt you were inventing something as you went along.

Mr. Welles wanted to seize every moment. He didn’t want one bland moment. He made you feel you were involved in a wonderful event that was happening before your eyes.

Even with rehearsals, Welles spent most nights rewriting the screenplay—bringing in new characters, creating new scenes. After one long night at the typewriter he called up Marlene Dietrich saying he had just written her a scene in his new movie and would she be so good as to come along tomorrow and film it? Of course, Dietrich was delighted to do so—as indeed were many of the other actors who were taking pay cuts or “guesting” in the movie—all because they recognized Welles’ genius and wanted to work with him.

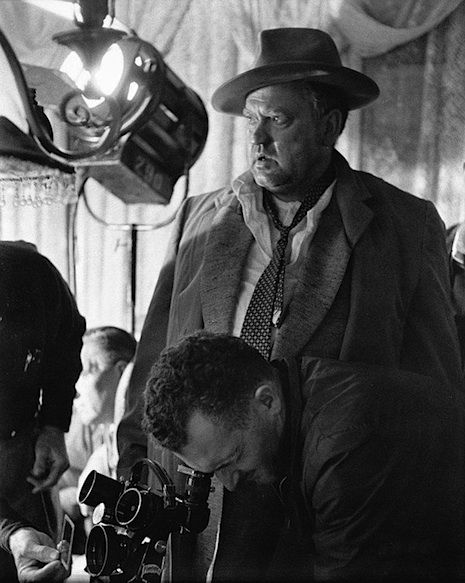

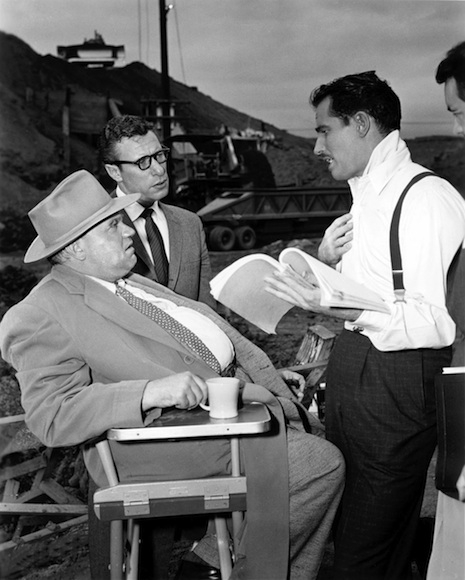

But the studios still didn’t trust Welles. They planted spies on set who fed information back to front of house. Welles was wise to their game. On day one of filming, he arrived on set at 9am and had the first set-up finished by 9:15. By 9:25 he had finished the second. By the end of the day, Welles had shot eleven minutes of script. To the studio finks it looked like Welles had been tamed, but he was actually playing them—the set-ups were mainly close-ups or long shot dialog scenes. After a few days of such phenomenal turn-over, the spies went quietly back to their desks and Welles was left to get on with the movie he wanted to make.

Don’t interrupt, genius at work.

This was all fine until it came to editing the movie. Welles didn’t get on with the studio’s first choice of editor. The next thankfully understood exactly what Welles was doing and the pair cut a movie that was based on rhythms and innovative non-linear juxtapositions of scenes. For example, one scene would be cut with another scene—either happening concurrently or slightly ahead of the narrative. It then cut back to the end of the original scene. The audience were being given knowledge of events to come and insight into the actions of the characters. The editing style was about a decade or so ahead of its time. When the studio execs saw a cut of the movie in Welles’ absence—they freaked, barred Orson from the studio, reshot some of the material, shot additional scenes, and brought in a do-it-by-numbers editor who recut the whole thing in linear form.

In other word, the studio fucked it up—which they probably realized after the fact as they released Touch of Evil as a B-movie support to the Hedy Lamarr feature The Female Animal. Still Touch of Evil had enough of Welles’ creative genius to make it a powerhouse of a movie—one that has understandably grown in critical stature since first release. However, the film effectively finished Welles’ career as a Hollywood director.

More from behind the scenes of Orson Welles’ ‘Touch of Evil,’ after the jump…