Spencer Kansa, author of Wormwood Star: The Magickal Life of Marjorie Cameron (Mandrake) contributed this interview with David Sylvian:

On the heels of his current release Sleepwalkers, a compilation of some of his most hauntingly beautiful collaborations from the last decade, David Sylvian looks back over his life to reminisce about his earliest influences, and pays tribute to some of the artists who have inspired him along the way.

Spencer Kansa: Time travelling back to the mid-70s, you went from getting kicked out of school straight into management and then you were signed within two years, that’s really phenomenal isn’t it?

David Sylvian: Yeah, I didn’t think of it as being phenomenal at the time, I took it all rather for granted (laughs). I thought “I’m owed this,” for some ungodly reason. But looking back, I realize, yes, that I was obviously very blessed, and am very blessed. I mean the difficulties that I’ve had in my life don’t compare to the difficulties other people face. But that I’ve been able to pursue music is obviously a gift.

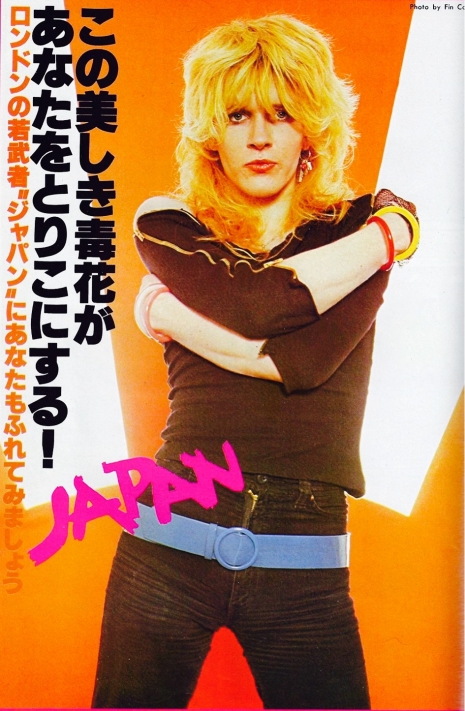

SK: You grew up in Lewisham. What was it about that part of South London that produced all these glamorous pop stars, cos Boy George also came from Lewisham didn’t he? And you also had the whole “Bromley Contingent” –the Bowie punks like Siouxsie Sioux and Billy Idol—just down the road.

DS: I think the only way I can view it is that it was so unbearably dull (laughs). It was a place of such convention. There was no colour, and it was an incredibly insensitive world. You couldn’t be different. You weren’t allowed to show certain sides of yourself, y’know. It was tough.

SK: Was it the Bowie influence or do you think the council put something in the water?

DS: (Laughs) I think the whole glam rock thing was a big influence. I mean it was Marc Bolan who first opened the door and it was just a release. I think there was a whole generation there just waiting to stick the pancake make-up on.

SK: Well, you may not be aware of this, but do you realize that because of your influence if you were a schoolboy in the early to mid-80s and you went to school without wearing make-up, you risked being bullied or even expelled.

DS: (Laughs) Yes I know! I always think it’s hilarious ‘cos I remember when we were like 13 or 14, and Mick (Karn, Japan’s bassist,who recently passed away) and I getting our ears pierced at that time, and oh the grief we got for it, y’know, from everyone! The traditional, usual places, building sites and what have you. Now you can’t go past a building site without some guy with earrings (laughs). I find it hilarious. It’s amazing how things change over time and such a short time too. But superficial things like that may change, but deep down people still harbour the same prejudices and they look for different signs to express that prejudice. That is truly amazing to me.

SK: I know you don’t like an awful lot of your early material, and you’ve said that “Ghosts” was really the kind of launch pad into your solo career, but can a case be made that there is a through-line from say “The Tenant” to “Despair” to “Nightporter” to “Ghosts” and then into your solo work.

DS: Sure, sure yeah. There’s a development and it’s very, very apparent. You could say that the first two Japan albums were an act of concealment, and from that point onwards the act of creating those albums was trying to pare away all of that, and trying to let something of myself come through, to allow myself to be that vulnerable. And I reached that point with “Ghosts,” that was the breakthrough. But getting there, there was “Nightporter” and there were other bits and pieces that spoke of emotional states that were very, very real to me. But they were dressed up in other storylines or ideas that I came up with.

SK: At that time you were far more interested in the New York punk scene, like Patti Smith and Richard Hell, than you were with the Kings Road punks that were happening back home. Was that because it was far more literary than what the Sex Pistols and others were doing?

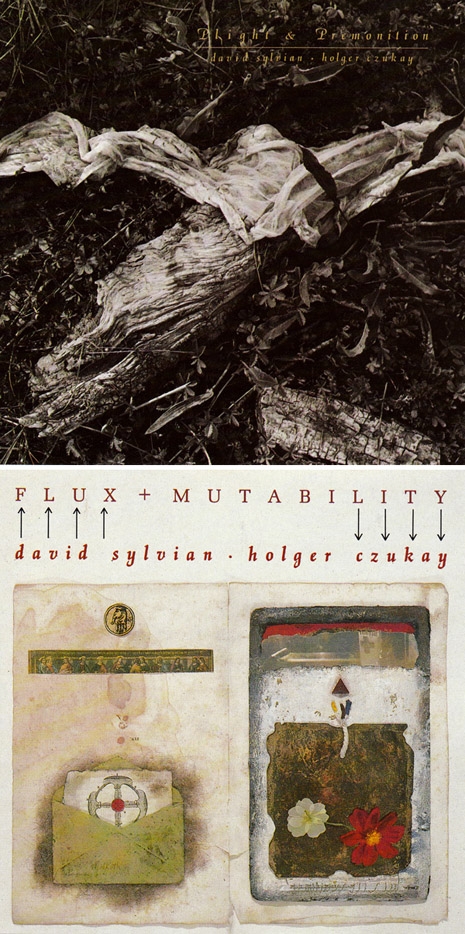

DS: Yeah, for sure. You could recognise an intellect at work, particularly in Patti’s early work like Horses which was quite an important album at that time. Actually, I was never attracted to the British punk movement at all. I celebrated the spirit of it. As unlikely as it seems we were very much part of that spirit at that time. It was a matter of ‘well we can do that, pick up our instruments and go’ and I’m still drawn to the non-musician cos I really love that spirit of exploration, normally as a result of not having the technical expertise to work otherwise. So how do you work around your lack of ability? You’re forced to be more creative. Holger (Czukay) and I are always laughing at the fact that the two of us create music together, two non-musicians! It’s entirely inspiring.

SK: Cos you’re pulling something out of yourself that you didn’t know you had.

DS: Yeah, or you come up against a problem; ‘well if I was a proficient pianist I would put in a piano solo here, but I’m not so what can I do?’ So you manipulate the studio to work to your own ends. There are no rules in that respect. You’re basically trying to break them. You’re cheating. ‘I can’t do that so what can I do instead?’ So you become far more inventive, and I really enjoy working with people with that mind set.

SK: Talking of collaborations, how did the idea of Japan working with Giorgio Moroder come about? Did you like the stuff he’d done with Donna Summer, or was it purely to see if you could go in another musical direction?

DS: Yes, in a sense. I think we were ready to move into an area of music that was more electronically based, and at the time I’m not sure whether it was management or the record company that was pushing Moroder. He had just produced an album for Sparks which we thought was interesting so we thought we’d give it a go.

SK: There’s a great photograph of you two in the studio, where you’re looking very bemused by everything, and he looks like Inspector Clouseau with his bushy mustache.

DS: That’s right! That’s who he used to remind us of, Clouseau. He was this kind of funny, little, slightly bungling character. It was an odd little experience, and I just think it set the ground for Quiet Life. It was almost like being a songwriter for hire. It was one of those experiences: “we’ll throw you into a studio in LA with Moroder” and he dishes out some old demo from his stack and says “Try working with this” and it’s like “Okay.” It was odd but not unpleasant.

SK: Throughout your work you’ve incorporated influences from outside music, from literature, painting and cinema. The work of Jean Cocteau has been very important to you, was that because he was so wonderful at evoking the dream state?

DS: Yeah, he made the invisible world tangible, and I’ve existed in that world (laughs). I had existed in that world a long time but it was always denied by those around me, as a delusion. So to find somebody writing about it and exploring it in film was like finding a friend. And to be honest, I think I’ve incorporated too many references in my work to other writers and artists. But the reason for doing so was that it was my community. I didn’t have one in the physical world. So I found like-minds through the work of others and I drew them into my work as a result. As a band of like-minded individuals, dead or alive, it didn’t matter. I sort of bonded with them.

SK: Like soul brothers.

DS: Yeah, and I felt a very close connection with Cocteau for a while. I really felt his presence and the same happened with Joseph Beuys. I mean, Beuys is still one of the most important artists for me. I was actually trying to make contact with him when I made the Gone to Earth album. I used a quote from him on it as you know, but I was actually gonna try and get Beuys to come in and record throughout that whole instrumental side, just quotations coming in and out, which would’ve been amazing. But as I was driving back from the studio one evening I heard that he’d died. But he’s been so present in my life at different points in time. He’s turned up in dreams and his presence has been very tangible. So often times in my life the presence of these dead artists have been more tangible then some of the people living around me.

SK: I always assumed you were a big Dirk Bogarde fan too, because you cribbed a song title from his film Nightporter.

DS: (Laughs) You’re right! Actually I did like some of Bogarde’s work, particularly the films he did with Visconti and Joesph Losey, I really enjoyed those.

SK: You’ve used a lot of paintings on the covers of your albums over the years, starting with the Frank Auerbach portrait on the cover of Japan’s live album Oil on Canvas. How did that come about initially?

DS: Well, I had a problem looking at visual art up until I saw that painting of Auerbach’s. I would walk around galleries, and I would appreciate the beauty of some of the work, the abstract nature, blah, blah, blah, but I was never moved. Not like a piece of music would move me or a poem. So I was quite unprepared for the experience that I had with the Auerbach, and I can’t tell you what I did or if I did anything to prepare me for that experience. I was just open to that moment. I must have been in a very open state of heart and mind, and was just blown away by one particular image. And the experience was as intense as any experience I’d had in music, and that was exciting cos I just didn’t think it possible. And since that time I’ve had that experience on a number of occasions with a variety of different artists. And it’s just a matter of being open to the work and also giving the work time. If you’re gonna go down to the Tate Modern, don’t try and see it all. Just think “Well I’ll walk through all these rooms but I’ll stop in front of three works and spend some time with three that appeal to me and see how I get on” and you’ll be amazed at what happens.

SK: Some spiritually minded people believe that rock ‘n’ roll is bad for you because the path to spiritual life means quieting the mind and rock ‘n’ roll is all about stirring the visceral. Has that had a bearing on your music? Did your music have to become more meditative in some sense?

DS: I think it had that quality to begin with, particularly once I moved into the solo work, it started to take on a quieter form for me. I just had the confidence to go there. I guess working with Japan, the band was uncomfortable working with the quieter material. They always wanted to do something a bit harder, something they could get their teeth into. I was being more and more drawn to these quieter compositions, and when I got the positive response to “Ghosts,” and that being something of a breakthrough to me as a writer, I realised ‘well I can pursue this avenue and it’s OK,’ every album doesn’t have to have these power pieces on them. And so I think I naturally fell into that style of writing because it so much suited my own nature. But there was a spiritual search going on that accompanied that which enabled the work to actually get quieter and quieter in some respects. But I don’t necessarily agree with the people that think about rock ‘n’ roll in the way you just described. To me, Robert Fripp is an intensely spiritual man and makes work that conveys that. There’s a powerhouse there, a very powerful music. So I don’t think that runs true. It’s so much to do with the heart and mind of the creator of the music. What are his or her motivations behind making the music? What emotions are you trying to stir in your listener? Where are you trying to take them? Those are more important issues than the genre of music in general.

Sleepwalkers is available now on Samadhisound.