For a man as superstitious as Federico Fellini the omens of 1973 were not good.

Too many friends were ill or dying; his private life was the focus of the paparazzi with claims of affairs with various young starlets; his relationship with his wife Giulietta was almost at an all-time low—though she continued to appear with the great director at functions like, as one acquaintance suggested, a politician’s wife out canvassing voters; and his usual life of extravagance was severely curtailed as the tax man was after him for non-payment of taxes. Things were not looking good. And Fellini was about to turn fifty-three which, by his own estimation, was on the back slice of life.

That summer, in need of money and a desire to keep working, Fellini agreed to make a movie on the life of Casanova for producer Dino de Laurentiis.

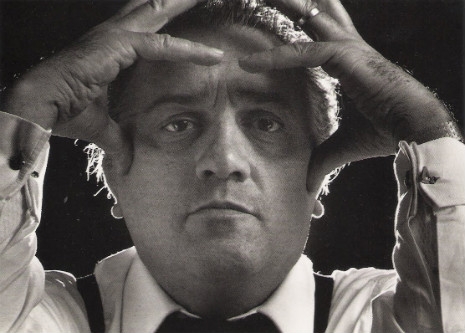

Fellini had often hinted that he would one day make a film about Casanova. He used it as a ploy to raise money for his other film projects—-Yes, yes, I’ll make ‘Casanova’ one day but now, now I want to make this….whichever film was his latest obsession. Fellini probably never had any intention of making a film about the great lover as he loathed Casanova. He saw in him some of his own negative traits which he hoped he could exorcise by making this damned film. He said:

“After this film, the moody and unreliable part of me, the undecided part that was constantly seduced by compromise—the part of me that didn’t want to grow up—had to die.”

Fellini was also aware that he perhaps subconsciously placed all his fears and the “anxiety [he couldn’t] face in this film,” adding that “Perhaps the film was fed by fears.” This unease sapped Fellini’s confidence and led him to believe he should have let this film project go as he feared Casanova would be “the worst film I have ever made.”

De Laurentiis was aware of Fellini’s misgivings but chose to ignore them. He knew with Fellini’s name attached to a film about Casanova, he could break the American market. Indeed, he favored an American actor to play the lead. He considered Marlon Brando, then Al Pacino, before finally deciding on the newly crowned “world’s sexiest man” Robert Redford to play Casanova. One can see the cartoon logic—world’s greatest lover must have considerable sex appeal. Robert Redford has sex appeal ergo Redford is Casanova.

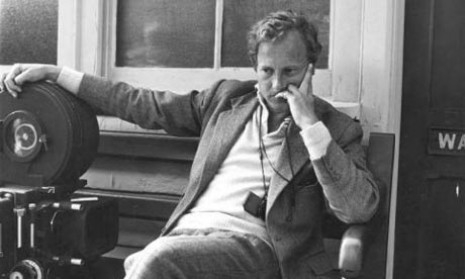

Fellini baulked at the choice. He wanted Marcello Mastroianni—an actor he could depend on. Unfortunately, Mastroianni was unavailable. While de Laurentiis searched for another international name (he also considered both Michael Caine and Jack Nicholson) to sell the picture to the US, Fellini started writing the script with his collaborator Bernardino Zapponi.

Zapponi brought his experience as a writer and knowledge of Casanova to the project. He arrived at Fellini’s office with several volumes of Casanova’s biography, only for the director to tell him such source material was not needed, as facts were anathema to imagination. This, Fellini explained, would not be a biographical film but rather a movie that filtered the director’s own thoughts on sex and death and aging thru the prism of Casanova. As Fellini later explained:

“I never had the intention to recount complacently, amused and fascinated the amorous adventures of Casanova.”

Instead he was to be:

“A prisoner as in a nightmare, as immobilised as a puppet, he reflects continually on a series of seductive and disturbing faces which succeed only in incarnating each time a different aspect of himself.”

Or as he had once said in an interview with the BBC:

Everything is autobiographical. How is it possible to live outside of yourself? Anything we do is also a testifying of yourself. If a creator makes something that pretends to be very objective, it is the autobiography of a man who is very objective…

...How is it possible to do something outside of your myth, of your world, of your character, of your history, of yourself?

It was becoming slowly apparent to de Laurentiis that this was not the sex ‘n’ costumes film he had intended to make. In July 1974, de Laurentiis pulled out, telling Variety other work commitments prevented him from giving Fellini’s Casanova the attention it demanded. Fellini sought to raise the money himself and eventually brought in Alberto Grimaldi to produce the film. He also managed to raise money from Universal Studios by bringing in Gore Vidal to write a new script. While Vidal’s script was shown to the studio to raise cash, it was never used in the final film.

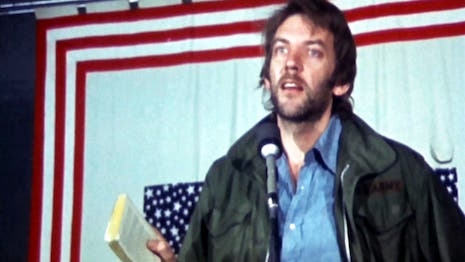

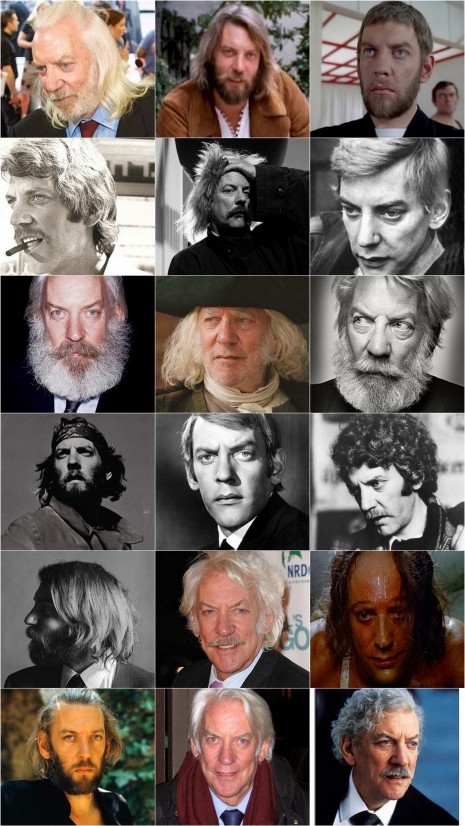

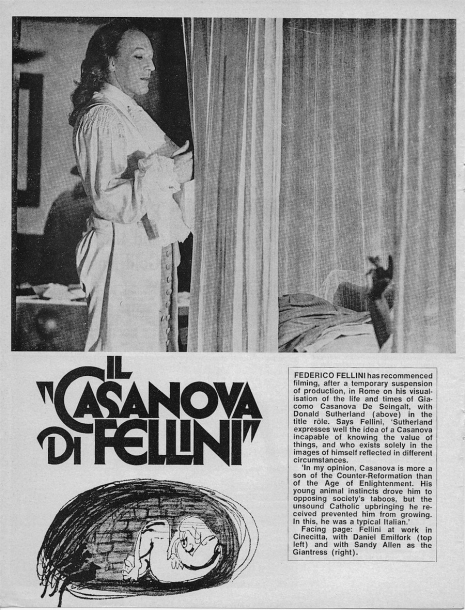

During all these behind-the-scenes manoeuvres, rumors spread through the press that Donald Sutherland was to star as Casanova. It’s difficult to ascertain who exactly first suggested Sutherland but his “candidature” for the role was “built up from simple repetition of the rumor.” To help this rumor along, Sutherland sent Fellini a highly flattering letter and twenty roses. Fellini wasn’t convinced. He still wanted the unavailable Mastroianni.

Looking for advice, Fellini visited a clairvoyant, Gustavo Rol, who claimed to have made contact with Casanova. During a seance, Rol filled page after page of notes from the great Casanova aimed at helping Fellini make his movie. When he left the seance, the director read some of the notes Rol had transcribed, which offered the sexual advice never to make love standing-up or after a meal.

Without Mastroianni, Fellini agreed on Sutherland to play Casanova. When asked why? Fellini declared:

“I need him. He’s a sperm-filled waxwork with the eyes of a masturbator!”

Sutherland told Time Out that he would not have played the role for any other director:

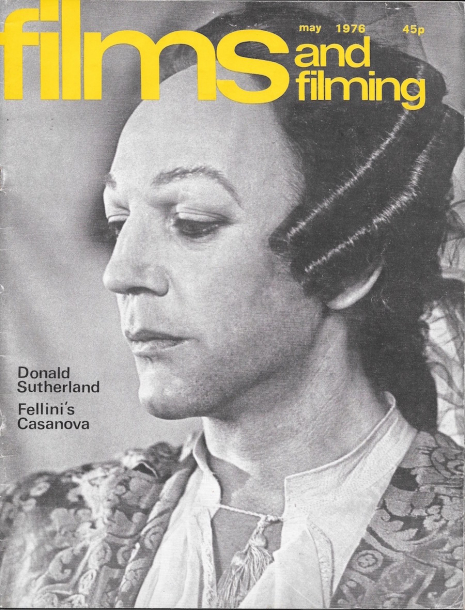

“I’m not playing Casanova. I’m playing Fellini’s Casanova, and that’s a whole different thing.”

It certainly was different as Sutherland soon found out when they met:

Walked into La Scala, him warning me that they wanted him to direct an opera and he was not going to do one. I remember three guarded doors in the atrium as we walked in. At the desk the concierge, without looking up when Fellini’d asked to see the head of the theater, demanded perfunctorily who wanted to see him. Fellini leaned down and whispered, truly whispered, “Fellini.” The three doors burst open.

With that word the room was full of dancing laughing joyous people and in the middle of this swirling arm clasped merry go round Fellini said to the director, “Of course, you know Sutherland.” The director looked at me stunned and then jubilantly exclaimed, “Graham Sutherland,” and embraced me. The painter Graham Sutherland was not yet dead, but nearly. I suppose the only other choice was Joan

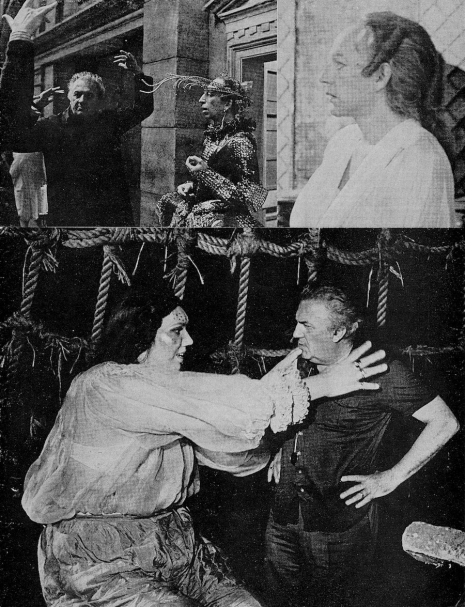

Sutherland had two millimetres filed from his teeth, his eyebrows removed and his hairline shaved back by two inches. He wore a false nose and chin. Fellini had turned Sutherland into a puppet—a mere mechanism for telling his story. On set, he never called him “Donald” or Mr. Sutherland” but addressed him as “the Canadian.” He offered little in the way of direction or support and could be very disparaging. “That poor guy,” Fellini said, “He believed he was going to become him.”

“Sutherland!—the incarnation of a Latin lover. He had two tons of documentation under his arms. I told him: ‘Throw out the lot. Forget everything.’”

Yet Sutherland was magnanimous in writing about his experience working with Fellini:

I was just happy to be with him. I loved him. Adored him. The only direction he gave me was with his thumb and forefinger, closing them to tell me to shut my gaping North American mouth. He’d often be without text so he’d have me count; uno due tre quattro with the instruction to fill them with love or hate or disdain or whatever he wanted from Casanova. He’d direct scenes I wasn’t in sitting on my knee. He’d come up to my dressing room and say he had a new scene and show me two pages of text and I’d say OK, when, and he’d say now, and we’d do it. I have no idea how I knew the words, but I did. I’d look at the page and know them. He didn’t look at rushes, Federico, the film of the previous day’s work. Ruggero Mastroianni, his brilliant editor, Marcello’s brother, did. Fellini said looking at them two-dimensionalized the three-dimensional fantasy that populated his head. Things were in constant flux. We flew. It was a dream. Sitting beside me one night he said that when he had looked at the final cut he had come away believing that it was his best picture. The Italian version is really terrific.

The film’s production was delayed by strike action and then seventy-four reels of film were stolen and ransomed. This meant Fellini had to change his film. Some scenes were dropped, others edited to fit the footage available. The finished movie bombed with the critics. At best, it was considered a misfire, at worst a disaster. Sutherland was given the unenviable task of attempting to deliver an intelligent and considered performance to a director who only wanted a marionette to play the role. Fellini’s abhorrence of Casanova undermined his ability to make a work of art or even a film that would resonate with an audience. The film could be admired but not always liked.

Fellini’s final verdict on Casanova was that it seemed to him his “most complete, expressive, courageous film.”

More ephemera from Fellini’s ‘Casanova,’ after the jump…