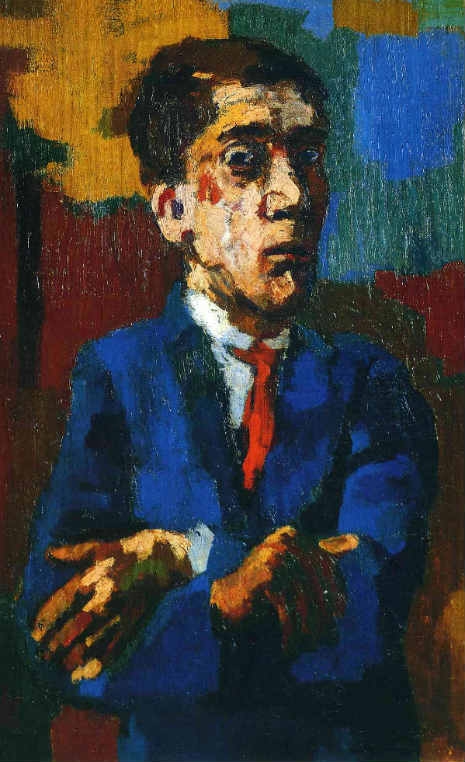

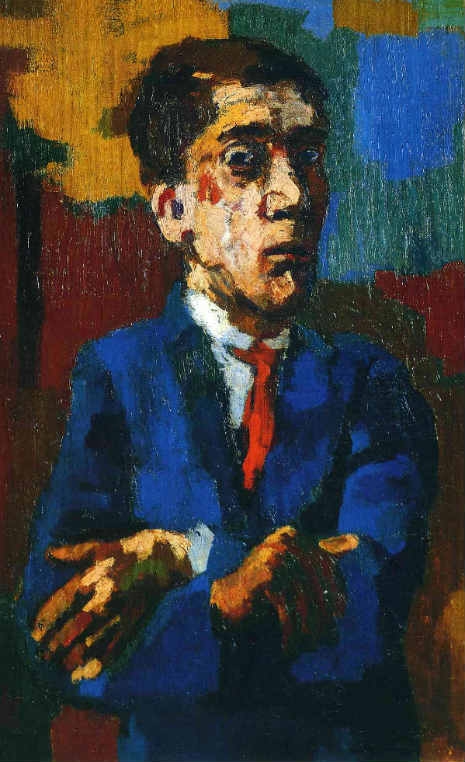

The artist, poet and playwright, Oskar Kokoschka sent the following letter to a young German prisoner of war, in 1946. In it he advised him to be warmed by love ‘the sight of our neighbor, other people, a foreign nation, another race,’ in which the ‘embrace of love will illumine the choice, form and shape of a new order of humanity.’ Kokoschka understood the young man’s trauma, having himself served as a Dragoon in the Imperial Austrian army, during the First World War, where he slithered in trenches through ‘bottomless mud,’ until he was seriously wounded and considered too mentally unstable to fight - the twisted logic of this was not lost on Kokoschka. Later, he was the focus of hatred and bigotry, when his art was deemed ‘degenerate’ by the Nazis. It forced Kokoschka to flee Austria for Prague, before then moving to Ullapool in Scotland, where he remained for the duration of the Second World War.

In this letter, Kokoschka expounds his belief in the importance of art and the artist that could show the ‘way up from subjection of blind obedience to human freedom.’

To a German Prisoner-of-War (Fritz Shahlecker)

[London,] 4 July 1946

A close friend showed me the drawings you made in the camp in England. He told me of your prospects of soon regaining your freedom and returning home to Tübingen. Like many of your fellow-Germans, you were abused in your early youth by a criminal demagogy and thrown into a war of aggression, during which the authority of human precepts was thoroughly and totally suspended, and which appears even now to threaten the future validity of those same precepts.

As an older man, I am in a position to make comparisons which shed light on the changes that have taken place in the moral sphere. That gives me a right to offer a younger man some advice that may come in useful when you are home again. After every great disappointment - in your case, when one has been the victim of a betrayal - one’s insight is clouded, because one is always overcome by weariness at the same time. The tendency to feel sorry for oneself is only a natural consequence of that weariness. You are honest in your drawings, but it seems to me that you tend towards the idealized view which comes from being in the center of a world that one is trying to rebuild. In your drawings you are trying to give shape to a new world with artistic expressive media available to you, after the reduction of your old world to ruins. You want it to be a human world, in contrast to the physical, materialistic world where naked force ruled, and in my view that is the hopeful and promising aspect of your experiment.

But the advice I would like to give you, however great your present need and poverty may be, is this: stop surrendering to a tendency to study yourself alone and to forget that a sentimental outlook is just as sure to lead to waste and failure as the entire order that is collapsing before our eyes today. That order sprang from individual egoism, and was helped to ripen by nationalistic narrowmindedness. Humanism was believed dispensable. This materialistic attitude found its complete embodiment in Fascism. Bear in mind that your personal need and poverty, both physical and spiritual, are nevertheless infinitesimal compared to the need and poverty of the children abandoned to savagery in today’s world. If your heart turns in hope to the work of rebuilding, because you are young and want to do good, you must help to make a better world for these children. You saw for yourself that what was achieved by the sword came to nothing in the end, therefore take up your pencil in the hope of doing better. You do not succeed in expressing anything about the pain throbbing in mankind today, because you are not yet able to give shape to genuine emotions. It will be like that for as long as you idealize yourself as a man of sorrows, instead of looking for the redeemer in every innocent child. The child can truly be the redeemer, if we can genuinely believe in the possibility of a better world. Sentimentality does not help us to discover new worlds, it makes us cling to the past in fascination. The new world can only be given shape if we love our neighbor. If we are warmed by love, the sight of our neighbor, other people, a foreign nation, another race, will enable us to shape a new image of the world, in the contemplation of which the isolation of the individual and his nameless torment in a ruined world will give way to the splendor in which the embrace of love will illumine the choice, form and shape of a new order of humanity. All art, that of the great epochs as well as that of primitive cultures, that of colored races as well as our own folk art, is rooted in this soil, in which the moral man has vanquished dust, decay and force. Man overthrows the dictates of physical laws and the dominion of blind elements, and by that means fights his way up from subjection of blind obedience to human freedom.

Art is a means of feeling our way forwards in the moral sphere, and it is neither a luxury of the rich nor the rigid formalism that comes out of the theories of the academies. The modern art of the present time also tends towards arid formalism. Art is like grass sprouting from the frozen earth at the end of winter, like growing corn, and like the spiritual bread in which the human inheritance is passed on to future generations.

In hope that you will find the inner strength to practice the spiritual office of an artist in the future, I leave you with my best wishes,

Yours, Oskar Kokoschka

‘Oskar Kokoschka Letters 1905-1976’ is published by Thames and Hudson.