At the height of Bond-mania during the Cold War in the 1960s, some sixty applications arrived every week at the desk of Lieut.-Col. William (“Bill”) Tanner, Chief of Staff at the British Secret Service. That might not seem much in today’s money considering how many billions of texts and emails randomly ping across the world, but these letters were long-considered, deftly-composed, neatly hand-written in the applicant’s best script, and then posted via mail in an envelope with a stamp purchased from the post office (closed Sundays, half-day Wednesdays and Saturdays) to arrive a day or two later on Lieut.-Col. Tanner’s desk.

The writers of these letters were not applying for “clerical or menial grades” but wrote in the hope of being trained as an agent in the “00 Section, the one whose members are licensed to kill.”

Unfortunately for these well-intentioned young men and women, this was not the way by which the Secret Service recruited its spies. Lieut.-Col. Tanner wrote back to each hopeful applicant to say so—but this “went against the grain. So much keen ambition and enthusiasm shouldn’t be allowed to go to waste.”

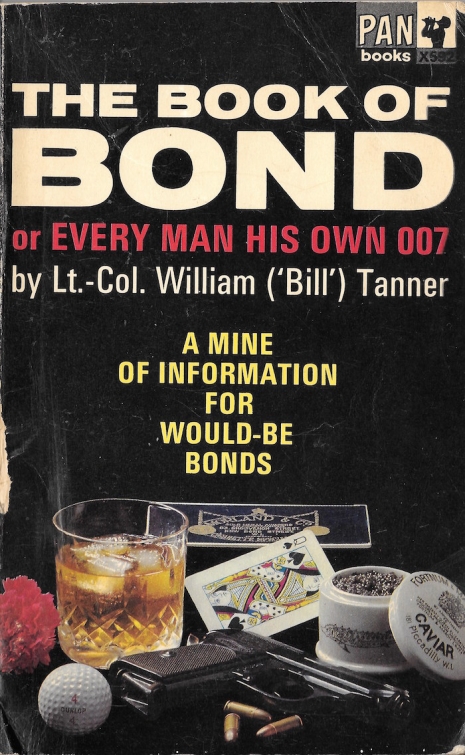

When he retired from the Service, Tanner decided to do something about this. He compiled The Book of Bond or Every Man His Own 007, which contained “a mine of information for would-be Bonds.”

Of course, Lieut.-Col. William (“Bill”) Tanner (retired) was a fictional creation—the nom de plume of that brilliant writer Kingsley Amis, who was a long-time fan of Bond and his author Ian Fleming. Using Fleming’s novels as his source material, Amis compiled “[a] glorious [tongue-in-cheek] guide to easy Do-It-Yourself Bondmanship…how to look…what to wear, eat, drink and smoke…”

Under the opening chapter on “Drink,” Amis listed James Bond’d favorite cocktails, which included “The Vesper” as featured Fleming’s first Bond novel Casino Royale. This is a “dry martini” served in “a deep champagne goblet” as Bond described it:

“...Three measures of Gordon’s, one of vodka, half a measure of Kina Lillet. Shake it very well until it’s ice-cold, then add a large thin slice of lemon peel…..”

Bond describes this concoction as his “own invention,” one that he planned to patent.

“I neve have more than one drink before dinner. But I do like that one to be a large and very strong and very cold and very well-made, I hate small portions of anything, particularly when they taste bad.”

But note, Bond’s favorite tipple can no longer be made with Kina Lillet or Lillet Vermouth, as they are no longer produced—see below.

In The Book of Bond, Amis detailed the recipes to Bond’s five favorite cocktails as follows:

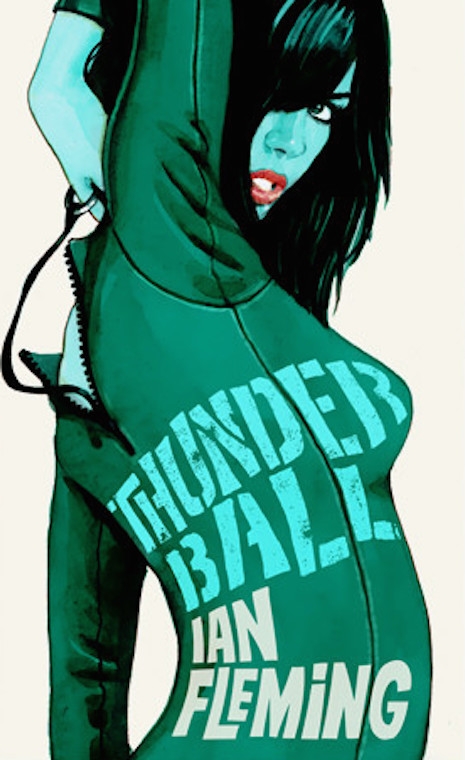

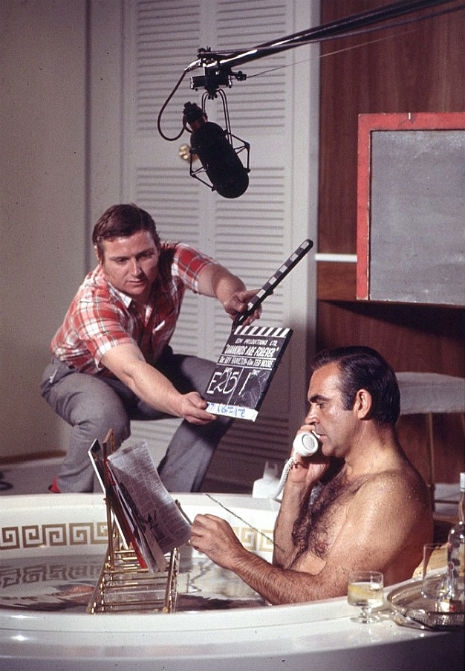

From ‘Thunderball,’ Ch. 14.

The Old-Fashioned

Made as follows—you don’t do the making, of course, but you should know how: Dissolve a level teaspoon of castor sugar in the minimum quantity of boiling water. Add three dashes of Angostura bitters, squeeze of fresh orange-juice, large measure of bourbon whiskey. Mix. Pour on to ice-cubes in short tumbler. Stir. Garnish with slice of orange and Maraschino cherry.

From ‘Doctor No,’ Ch. 14.’

The Martini.

Made with vodka, medium dry—say four parts of vodka to one of dry vermouth—with a twist of lemon peel. To be shaken with ice, not, as is more usual, stirred with ice and strained.

The full-dress, all-out version of this is

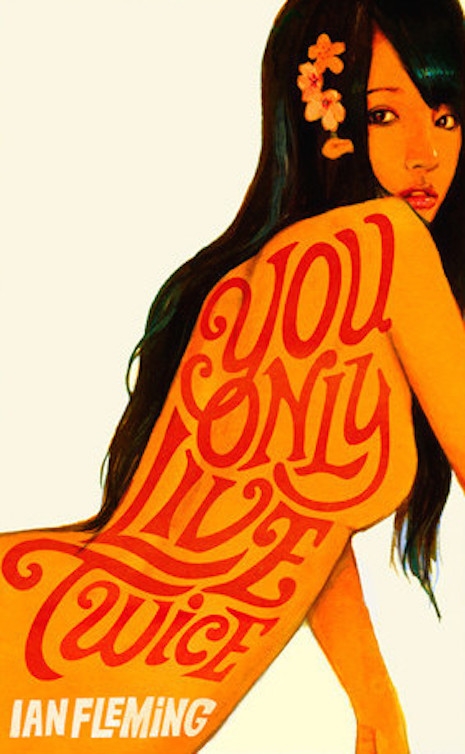

From ‘Casino Royale,’ Ch. 7.

The Vesper.You will have to instruct the bartender or waiter specifically as follows:

Take three measures of Gordon’s gin, one measure of vodka, half a measure of Lillet vermouth. Shake very well until ice-cold. Serve in a deep champagne goblet with large slice of lemon peel.

...

When the drink arrives, take a long sip and tell the barman it’s excellent, but would be even better made with a grain-base vodka than a potato-base one.

i) The original recipe calls for Kina Lillet in place of Lillet vermouth. The former is flavoured with quinine and would be very nasty in a Martini. Our founder slipped up here. If Lillet vermouth isn’t available, specify Martini Rossi dry. Noilly Prat is good for many purposes, but not for Martinis.

ii) Make sure the barman is very ignorant, or very deferential, or very both, before talking about vodka bases. Potato vodka is the equivalent of poteen, or bath-tub gin, and getting hold of a bottle of it through ordinary commercial channels wouldn’t be easy even on the far side of the Iron Curtain.

More after the jump…