It started with making false noses. Christopher Tucker was studying opera at drama school when he was asked to appear in a production of Rigoletto. He decided to give his character a noticeably larger hooter. He began fashioning different designs and discovered he liked making noses. That was when Tucker gave up Verdi and opera for a career as a makeup artist.

You may know the name, but if you don’t you will certainly know Tucker’s handiwork. He designed Mr. Creosote for Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life—“And finally, a wafer thin mint.” He came up with the designs for the lycanthropes in Neil Jordan’s werewolf fantasy The Company of Wolves. He also worked on Dune and even made an unfeasibly large prosthetic penis for porn star Long Dong Silver. Somewhere in among that lot you’re bound to have seen Tucker’s incredible craftsmanship.

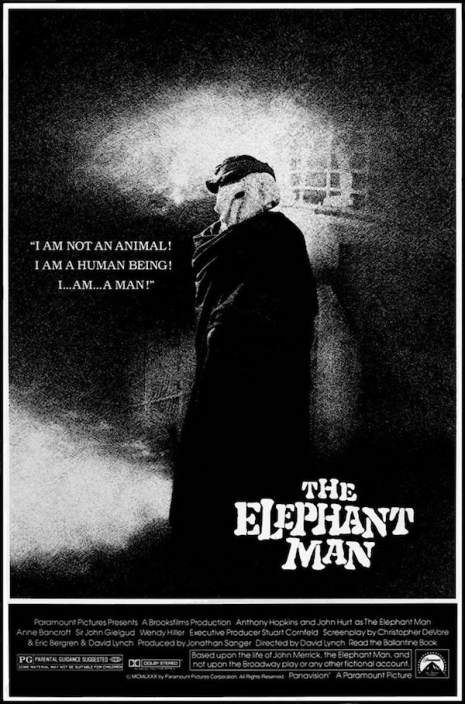

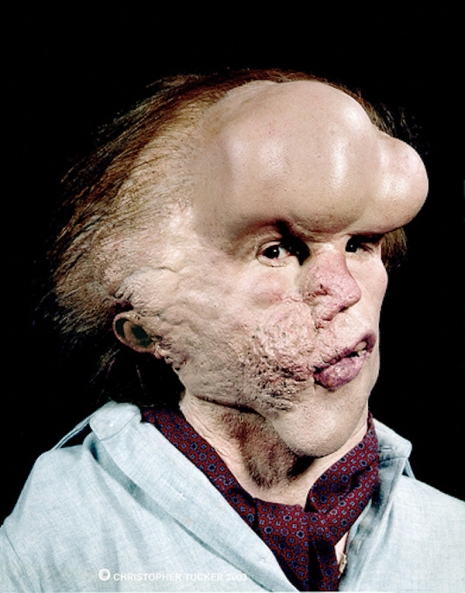

He is best known, however, for his prosthetic makeup designs for David Lynch’s The Elephant Man, in which he recreated the severe deformities of Joseph Merrick, a man whose head was grossly enlarged and his body disfigured by an unknown disease—it is still a matter of debate as to the cause of Merrick’s illness. Because of his deformities, Merrick was exhibited as a freak in Victorian sideshows. The main problem for Tucker was not to make his designs look like “a cheap horror” but as “something approximating but not an exact clone of the ‘Elephant Man’.”

Lynch had originally planned to design the makeup for Merrick himself but the enormity of the task and his inexperience almost left the film without its “Elephant Man.” Eventually, Tucker was called in to rescue the movie and create its unforgettable makeup designs.

Hurt as Joseph Merrick, or rather John Merrick as he is called in the film.

The late, great John Hurt was tasked with bringing Merrick to life on the screen. Hurt was one of those rare and subtle actors who brought tremendous sensitivity and humanity to each of his performances. He was one of those actors the press often “rediscovered” every so often—as they did after his performance as Quentin Crisp in The Naked Civil Servant, or when he appeared as the deranged emperor Caligula in I, Claudius, or the broken, drug-addled Max in Midnight Express, or the vulnerability he brought to the doomed Stephen Ward in Michael Caton Jones’s film Scandal. But Hurt never really went away. He was consistently good in all of his roles, so good that the press took his quality of acting for granted, and only commented on his work when he was truly exceptional.

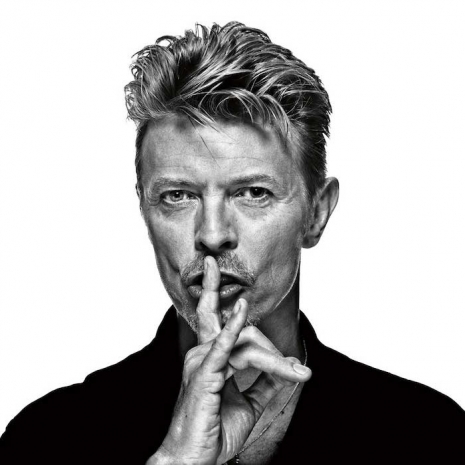

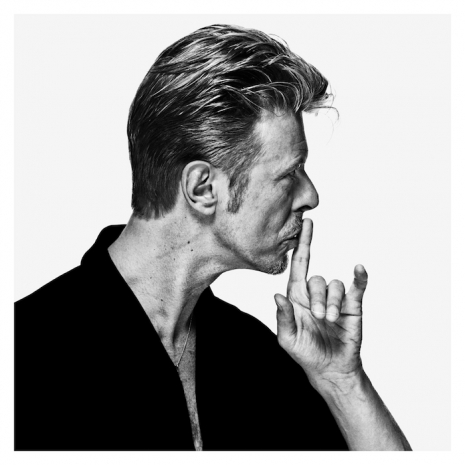

Tucker’s photograph of Hurt as Merrick.

It took seven to eight hours in makeup for Hurt to become Merrick. It then took up to two hours to remove the fifteen layers of prosthetics Hurt wore. The designs for the “Elephant Man’s” head and limbs were taken directly from original casts of Merrick’s body kept at the Royal London Hospital. The long, laborious procedure of becoming Merrick led Hurt to quip: “I think they finally managed to make me hate acting.”

The BFI has a fascinating interview with Tucker about his designs for The Elephant Man which you can find here, while below, Tucker and Hurt discuss the process of bringing Merrick to life on the screen.

Previously on Dangerous Minds:

David Bowie wows Broadway as ‘The Elephant Man’

‘The Elephant Man’: David Bowie on Broadway, 1980

‘Little Malcolm’: George Harrison’s lost film starring John Hurt and David Warner